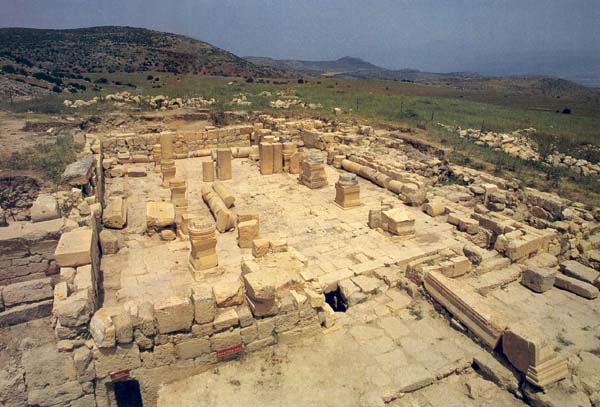

Meroth Synagogue, 4th-5th century CE

Zvi Ilan and Emmanuel Damati, “The Synagogue at Meroth- Does It Fix Israel’s Northern Border in Second Temple Times?” BAR 15-02, Mar-Apr 1989.

Meroth Synagogue

Remains from more than a dozen ancient synagogues dot the landscape of Galilee. What makes the ancient synagogue at Meroth (May-ROTE) unusual is not only the rich finds uncovered in its excavation, but the face that so much about this synagogue seems to fly in the face of widely accepted scholarly generalizations.

Until recently, no one even knew about the existence of the Meroth synagogue. Usually, ancient sites are discovered either by accident—someone unexpectedly stumbles on remains—or as a result of a systematic search in the course of an archaeological survey.

The site of Meroth, however, was discovered in a library 3,000 miles from Israel. I [Zvi Ilan will be speaking for himself in this section of our article] was examining some unpublished fragments of documents in the library of Cambridge University in England. The fragments had been part of a famous cache known as the Cairo Genizah (Geh-NEE-zuh),a a repository of old discarded documents kept for centuries in a Cairo synagogue. One of these, which dates to about the 14th century, contained a list of tombs of tzadikim (tsa-dee-KEEM), righteous holy men, buried in the land of Israel, giving the location of each tomb in geographical, or itinerary, order. The list located one of these tombs, the tomb of Rabbi Hinna, in Upper Galilee at Kfar Marous (Kfahr Mah-ROOS)’ the village of Marous. This was curious to me because Kfar Marous is mentioned nowhere else in the vast medieval travel literature.

I recalled that the first-century A.D. Jewish historian Josephus mentioned a similar sounding site, Meroth, in the same area. The location of Meroth is of considerable importance to historians because it was situated on the northern border of Israel at the end of the Second Temple period (mid-first century A.D.). Siting Meroth could locate this hitherto unidentified northern border of Israel. According to Josephus, Meroth was also an important fortified settlement during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 A.D.).

Scholars had long disagreed about the location of Josephus’s Meroth. Based on phonetic similarity, some suggested the Upper Galilee site of Meiron (May-RONE) as Josephus’s Meroth. Meiron has recently been excavated by a team headed by the American archaeologist Eric Meyers, who supported this identification, despite the fact that he found none of the fortifications that might be expected at Josephus’s Meroth. Moreover, Meiron was hardly likely to mark the northern boundary of Israel during this period, inasmuch as several Jewish settlements, including the very important site of Gush Halav, were north of Meiron.

Other scholars, again on the basis of phonetic similarity, sought to identify Josephus’s Meroth with a village in southern Lebanon named Maroun a-Ras (Mah-ROON ah-RAHS). But no Jewish remains have been found at Maroun a-Ras; it was a settlement in the land of Tyre.

So the problem of Josephus’s Meroth and the northern border of Israel remained. Could the unidentified Kfar Marous I found in the Cambridge University library provide the key?

The list I was examining provided some indication of the location of Kfar Marous because it was geographically ordered and contained mostly known sites.

Then, on an old map—from the days when Great Britain governed Palestine under the League of Nations’ Mandate—I found a village in the Upper Galilee also named Kfar Marous. Its location—about three miles west of the Biblical city of Hazor (Hah-TSORE)—fit exactly the location indicated in the geographical order of the sites listed in the Cairo Genizah manuscript. Depending on what I could find on the ground—or under it—I might be able to prove the following equation- The Arab village of Kfar Marous on the Mandate map equaled medieval Kfar Marous mentioned in the Cairo Genizah fragment in the Cambridge University library equaled Josephus’s Meroth. The northern border of Israel in late Second Temple times would be established.

The site of the Mandate village of Kfar Marous should be easy to fix, I knew, but it was in a military area, so special permission was needed to enter. Finally, four years after my discovery in the Cambridge University library, I was riding in a Jeep through a rough, isolated part of Upper Galilee, with the government inspector of antiquities for that area, Yosef Stefansky, hoping to locate an abandoned Arab village named Kfar Marous to see if we could find evidence of ancient occupation that might establish the northern border of ancient Israel.

As it turned out, we found this and more. In a matter of hours, we picked up pottery sherds dating to the Second Temple period. We also found poking through the ground—later confirmed by excavation—an impressive and extensive fortification wall.

Then we spotted—in an overgrown field, about 660 yards north of the Arab village, and hidden by clumps of grass—the edges of three column bases aligned in a row on a north-south axis. This was an area that had been Jewish throughout antiquity. Columns—and therefore column bases—from this period were used only in public buildings. The only major public buildings in Jewish towns and villages were synagogues. Moreover, in the Galilee, columned synagogues were aligned on a north-south axis, facing Jerusalem.

Within seconds of our spotting the three column bases, Stefansky and I shouted simultaneously, “It’s a synagogue!”

In a single day, we had located the northern border of Israel in the Second Temple period, identified Josephus’s Meroth and found a hitherto unknown ancient synagogue. Quite a day’s work! I am happy to report that the identification of Josephus’s Meroth with the later village of Kfar Marous has now been accepted by almost all scholars.

Having located the site, we of course wanted to excavate it, especially the synagogue. I immediately enlisted the assistance of Emmanuel Damati, an archaeologist from nearby Birya, and we now have worked together for five seasons as co-directors of the excavations at ancient Meroth. The remainder of this article is our joint effort.

The excavation work has been carried out largely by volunteers—from nearby Kibbutz Machanayim (Mah-khah-NEYE-eem), from a kibbutz called Kfar Ha-nasi (Hah-nah-SEE) founded in 1947 by immigrants from English-speaking countries and from nearby schools. Our workers range in age from 4 to 77. No one—from the dig directors on down—is paid.

The most exciting finds in the excavation at Meroth have been the extraordinary synagogue and its contents. The date of the Meroth synagogue proved a surprise. It was built at the end of the fourth or the beginning of the fifth century A.D. This was supposed to be a time of repression and poverty for the Jews. Byzantine law even forbade the construction of new synagogues. Yet the picture we get from Meroth is far different. Here is a community of Jews prosperous enough to build a magnificent new synagogue in the isolated reaches of Upper Galilee at a time when Christianity was the state religion of the Roman empire.

As originally laid out, the synagogue was built on the typical plan of the so-called Galilean synagogue- The prayer hall was rectangular with three entrance doorways in the southern facade—facing Jerusalem. The congregants would enter by these doorways and then turn around to offer their prayers in the direction of the Holy City, although at that time the Temple itself lay in ruins atop the Temple Mount.

Inside the synagogue’s prayer hall two rows of columns aligned north-south divided the room into a central nave and two side aisles. The prayer hall was quite large as ancient synagogues go—another indication of the town’s prosperity. On the inside, the prayer hall is nearly 60 feet long and over 25 feet wide. Benches lined the walls.

On the front of the building was a portico, or porch, supported by columns and topped by a triangular pediment with a so-called Syrian arch. The synagogue was two stories high. The second floor had balconies with benches for the worshippers. Access to these balconies was by an external staircase. Along the outside of the western wall we found part of a stairway that did not, however, date to the original construction of the synagogue. It was probably erected on the foundation of an earlier staircase that had also led to the balconies.

In front of the synagogue’s portico was a forecourt (or atrium) extending for nearly 25 feet. A well in the center of the forecourt presumbably provided water for the worshippers to wash themselves before prayer, just as Moslems do today. In accordance with rabbinic tradition, the synagogue is built on the highest spot in the settlement.

Until recently, scholars regarded columned Galilee synagogues with their southern entrances as a phase of synagogue architecture development that characterized the second and third centuries A.D., to be replaced in the fourth or fifth century by synagogues with a mosaic floor, a northern entrance and an apse for the Torah ark in the south (facing Jerusalem). This chronological scheme has not held up, however. Recent excavations have shown that such famous columned Galilee synagogues as Capernaum (KA-per-nowm)c and Chorazin (Khor-ah-ZEEN)d were in fact built after the third century A.D. The columned synagogue at Meroth—built in the late fourth or early fifth century—lends support to this late dating of Galilean-type synagogues, which in many cases were contemporary with synagogues that have apses for the Torah ark.

We must now conclude that the columned Galilee synagogue cannot be used as a chronological indicator; it is not typical of any particular century or two.

The forecourt in the Meroth synagogue is also unusual. No other Galilean synagogue is known to have had a forecourt. Until now, it was thought that forecourts were to be found only in so-called broadroom synagogues (with prayer halls wider than they are long) in Judah, south of Jerusalem, in Diaspora synagogues (as at Sardis in Turkey) and in such later synagogues with apses in Israel as Beth Alpha (fifth to sixth centuries) and Na’aran (sixth century). Now we have a forecourt in a Galilean synagogue. Apparently the forecourt was a later development in synagogue architecture that finally reached the Galilee and was used there even in synagogues with a typical Galilean synagogue plan.

Ornate cornices with floral designs—grapes and other fruits—decorated the exterior of the Meroth synagogue. One of the doorway lintels had a rosette design in the center; another had a tabula ansata. A tabula ansata looks like this- Picture. The center panel of the tabula ansata usually contains an inscription but this one is empty. The lintel of the main center doorway of the synagogue is beautifully carved, but is undecorated.

In the course of the excavation, we also uncovered five shaped stone blocks that had once formed part of an arch somewhere in the synagogue. On the short end of each block, sculptured leaves provided a frame for a picture. But very little of the five pictures—originally in high relief—survived. On one only a pomegranate and a fish tail survived; on another was stylized water spilling out of a bucket. The pictures were intentionally gouged out in the eighth century by Jewish iconoclasts under the influence of iconoclastic movements in Islam and Christianity. In 721 A.D. the Omayyad ruler, Halif Yazid II, ordered the destruction of all images. Other synagogues—for example, Capernaum—were also damaged by iconoclasts.

The traces of images that remain on the Meroth stones suggest that what the iconoclasts destroyed was a zodiac. Mosaic zodiacs have been uncovered in four or five ancient synagogues, so despite its pagan associations, the zodiac, perhaps adapted to the Hebrew calendar, seems to have been a popular element of Jewish iconography. If the Meroth stone blocks actually were part of a stone zodiac, it is the first stone example ever discovered.

Hundreds of sherds from roof tiles tell us how the roof of the synagogue was covered. Fragments of painted plaster tell us the walls were covered with frescoes, mostly in red.

Inside the synagogue’s portico (or porch), on the left as you enter, we found a carved doorway with a step leading down to it. This doorway in turn opened into a small room hewn into the bedrock. This may have been the Meroth synagogue’s genizah.

Originally, the synagogue floor was simply plastered. Then, perhaps 30 or 40 years later a new floor was laid. Until our excavation of the Meroth synagogue, every synagogue of the so-called Galilean-type (such as Capernaum and Chorazin) had a floor paved with rectangular flagstones. The Meroth synagogue also had such a floor, which was laid over the original plaster floor. But you can imagine our surprise when at the end of a long day’s digging, one of our volunteers suddenly discovered the edge of a mosaic under the flagstone floor and above the original plaster floor.

Meroth seemed to be breaking all the rules. Galilean-type synagogues in Upper Galilee were supposed to have paved flagstone floors. Mosaic floors were supposed to have been introduced later. Yet here was a mosaic floor (the second floor of the synagogue) which was later covered over with a paved flagstone floor (the third floor of the synagogue). In short, about 25 years after the original plaster floor had been replaced with a mosaic floor, the mosaic floor was itself replaced with a stone-paved floor. We can date this third floor quite accurately to about 475 A.D. That is the latest date of hundreds of coins we found underneath and between the flagstones, intentionally placed there to bring the building and its congregants blessings and good fortune—a widespread custom of tossing coins that has survived in various ways to our own day.

While scholars pondered the significance of a mosaic floor in a Galilean-type synagogue with a paved floor over rather than under it, our volunteers uncovered a magnificent mosaic whose content was just as surprising as the fact that it was there. A youth with a rosy complexion stands surrounded by weapons and armor. Above him are a helmet and a sword, below him an oval shield. Who is he?

In 1984, just a week before he died, Israel’s most famous archaeologist, Yigael Yadin, suggested that our mosaic depicts the youthful David after his battle with Goliath (1 Samuel 17). The helmet, shield and sword belonged to the giant. David, the future king, who has just slain the giant with his slingshot, now sits on Goliath’s shield. We are inclined to accept Yadin’s interpretation—perhaps the last of the brilliant insights of this great man.

But other interpretations of the mosaic abound. Another possibility is that the armor and sword are the accoutrements presented to young David by King Saul before the battle with Goliath.

Professor Mordechai Gichon believes he can identify the sword as a Roman cavalry sword known as a spatha. Professor Shimon Applebaum believes the emblems on the young man’s arm and thigh are Roman military unit insignia. This does not necessarily contradict the identification of the youth as Biblical David, however. The ancients commonly portrayed Biblical heroes in contemporary dress. Examples are to be found in the famous frescoes from the third-century A.D. synagogue at Dura-Europos in Syria and in the sixth-century A.D. mosaic of David playing the lyre and dressed as Orpheus in a synagogue floor in Gaza. In the Gaza synagogue, there is no doubt as to David’s identification because his name is inscribed by tesserae in the mosaic itself.

Unfortunately, the part of the mosaic at Meroth that depicted what the figure holds in his hand has not survived. Perhaps his slingshot? Or the head of Goliath? Or a twig of victory, a few tesserae of which can still be detected?

In the left corner of the mosaic are the Hebrew letters of a name, Yodan bar Shimeon Mani (Yo-DAHN bar Sheem-OWN MAH-nee) (Yodan the son of Simon Mani). On the basis of this inscription, some scholars have suggested that the figure in the mosaic is Yodan himself, perhaps a wealthy villager portrayed as a military hero. Other scholars deny this and argue that Yodan was simply the donor whose memory is preserved in the mosaic he financed. But the inscription seems to contradict this; generally donors’ inscriptions contain a formulaic verb, most commonly Dehir latov (Deh-KHEER lah-TOVE) (May he be remembered for good … ) followed by the name of the donor. The absence of such a formula in our mosaic inscription suggests that Yodan may be the mosaic artist, rather than the donor.

Professor Nahman Avigad suggests that Mani comes from the word mini which means “from me” and refers to the donor. Professor Joseph Naveh argues that Mani is a form of the word mane (an ancient standard monetary weight), thus indicating the size of the donation. Still others suggest Mani is a short form of Menachem. Perhaps it is the name of Yodan’s grandfather, the word bar (son of) being inadvertently omitted between “Shimeon” and “Mani.” Another possibility is that Mani is a corrupted form of the Aramaic memani, which derives from a Hebrew title memoneh, meaning an “appointed one.” Obviously, this scholarly debate is not likely to be settled soon.

For those of us at the dig, the disappointment of the mosaic was the fact that it didn’t extend beyond this particular frame. From its placement in the northern part of the prayer hall, it appeared that this was the last frame in a series, each frame containing a different picture. We carefully lifted part of the paving stones from the later floor, anticipating the discovery of additional mosaics. But only a few additional fragments were found, along with many loose tesserae.

Because the mosaic was so unusual and important, we decided to remove it to Jerusalem for display in the Israel Museum. This proved to be another fortuitous decision that led to unanticipated results. To make the removal of the mosaic easier, we dismantled part of the adjacent wall and lifted a threshold from the doorway leading into the synagogue from the north. Underneath the threshold was a small, rolled-up bronze amulet about 2 inches long. It was rolled up like a scroll and was intended to be worn around the neck, with a string through the hole. In ancient times, amulets were worn to exorcise evil spirits, to bring love and wealth or to petition for health (often by malaria sufferers). This amulet—as we should expect from Meroth—turned out to be unusual. The petitioner who had this amulet made for himself asked to be like God!

When the amulet was opened in the Israel Museum laboratories, it was found to contain a long Hebrew and Aramaic inscription, ultimately deciphered by Professor Joseph Naveh from a drawing by Ada Yardeni, who was able to discern the faint scratchings on the inside of the 5.5-inch-long amulet with the aid of a binocular microscope.

The 26-line inscription is a letter to God from a man named Yossai bar Zenovia (YO-SAI bar Zeh-NO-vee-uh) (Yossai the son of a woman named Zenovia). The mother’s name is always used in amulets; perhaps a petition offered in the mother’s name was thought to be more effective. In any event, Yossai asks to be given complete and absolute control over all the residents of the village. Yossai was obviously a man of great pretensions- “Let my word and my command be upon them as the Heavens are subjugated before God.”

Apparently we are witnessing a local power struggle within the Jewish community—and all stops have been pulled out.

Interestingly enough, a power struggle like this indicates a quite prosperous Jewish community. Internal struggles like this do not usually occupy this kind of attention when a poor community is struggling against an outside threat.

We have mentioned three floors—the original floor (phase IA—c. 400 A.D.), the mosaic floor (phase IB—c. mid-fifth century A.D.) and the paved stone floor laid above that (phase II—c. 500 A.D.).

Even in the earliest phase, a raised platform or bamah (bah-MAH) was built in the prayer hall on the southern wall between the center doorway and the western doorway. In phase II, this bamah was partly rebuilt and made larger. It is over 3.5 feet high and is one of the most beautiful bamot to have survived from an ancient synagogue.

Two pilasters supported a stone hood under which was placed the wooden ark that housed the Torah (Pentateuch), or scroll of the law. Near the bamah we found stone fragments that once formed part of the Torah shrine—small column drums, column bases and parts of engaged columns with beautiful spiral shafts. The engaged columns were once attached to the back wall of the Torah shrine. On one fragment of an engaged column shaft the stem of a menorah was engraved.

Another bamah was built on the southern wall of the synagogue, between the center door and the other side door. This bamah was probably used as a pulpit or as a base for the community leader’s chair, known as “The seat of Moses.”

Sometime during the first half of the seventh century an earthquake or other similar disaster badly damaged the synagogue. In the complete renovation that followed, the three entrances on the southern facade were closed—that is, the southern wall was rebuilt without them—and three entrances (only parts of two have been found so far) were built in the northern wall. The northern wall itself was moved about 4.5 feet to the south (see plan and reconstruction drawing).

In general, synagogues built in the third to fifth centuries have three entrances on the facade facing Jerusalem; later ones have their entrances on the opposite (northern) wall. In the earlier synagogues, the worshipper would enter and then have to turn around to face Jerusalem. In the later ones, the worshipper would be facing Jerusalem on entering the prayer hall.

In some synagogues—Meroth is an example—we find the change being made in the same synagogue. When the synagogue had to be rebuilt in the seventh century, the town decided to update its design. The original entrances in the Jerusalem facade were blocked up and new entrances provided in the opposite wall.

The threshold of the new entrance doors on the north are 4 feet above the stone floor of the prayer hall, so the worshippers had to descend into the prayer hall by a set of steps. The steps, which were made of wood, have long since disappeared; only the nails have been found.

When the entrance to the synagogue was transferred to the northern wall, the portico and courtyard on the south lost their function. They were then used as an area in which to build schoolrooms, as suggested in talmudic sources. In the eastern half of the former portico, a children’s schoolroom was built. The courtyard on the southwest was transformed into a beth midrash (bate meed-RAHSH), a house of study for adults. This is the first complete beth midrash study room ever found in an ancient Jewish settlement in Israel. The room measures 21 by 24 feet. Over its main entrance was a magnificent lintel, which we have recovered, inscribed with a quotation from Deuteronomy 28-6- “Blessed shall you be in going in and blessed shall you be in going out,” a fitting inscription indeed for a house of study.

Arches supported the roof of the study room of the beth midrash. The walls were covered with fine plaster, which was painted in bright colors. Stone benches lined the walls. The finest bench—on the western wall—has a recess in the center. This probably held the seat of the local sage and head of the beth midrash. Perhaps this was Rabbi Hinna, the sage mentioned in the Cairo Genizah fragment in the Cambridge University library that originally led us to Meroth.

The floor of this study room was covered with a mosaic, only parts of which have survived. One surviving frame describes “the end of days” and depicts a large amphora (am-FOE-ruh) of water; on one side of the amphora is a wolf and on the other a lamb, together with an inscription—the well-known passage from Isaiah 65-25- “The wolf and the lamb shall graze together.” Perhaps this inscription reflects the community’s yearning for peace and serenity during a period known for its turmoil and suffering.

Elsewhere on the mosaic floor are rams’ horns (shofarot) (show-fah-ROTE) flanking what appears to be a traditional representation of a Torah ark. This part of the room may have been used for prayers. Above the Torah ark in the mosaic are pomegranates and heart-shaped leaves; below the Torah ark are bunches of dates, all perhaps intended to recall the seven sacred fruits of the land (shiva’at haminim) (sheev-AHT hah-mee-NEEM).

The rebuilding of the synagogue in the seventh century, plus the addition of the children’s schoolroom and the beth midrash complex, testifies to the vitality of the settlement at this late date. The Meroth synagogue continued to function for hundreds of years, therefore, under Islamic and Crusader rule, until the end of the 12th century A.D.

If this was true at Meroth, it was probably true of synagogues at other settlements in the area as well. At two sites, Gush Halav and Dalton, we are told in literary sources, there were resident book copiers. All of this suggests that Jews continued to live and even thrive in some areas of Palestine and that they managed not only to earn their living as farmers, but also to maintain institutions of study and prayer.

Yet this time, like previous centuries, was also a period of danger and fear. Beneath the synagogue, we discovered a series of subterranean caverns. To date eight rooms have been uncovered, linked to each other by narrow passages. One of these rooms, which has an arched opening, served as a mikveh—or ritual purification bath—for synagogue officials. (Another, much larger, mikveh north of the synagogue served the general population.) Another cavern was used at one time as a water cistern. Some of these caverns may even predate the synagogue. But we suspect that the primary purpose of these underground caverns was to provide hideouts in time of danger. It is even possible that they were connected to some village houses by means of tunnels.

A final discovery that reflects both prosperity and danger was a hoard of 485 coins, 245 of gold and 240 of bronze, found under the floor of the synagogue store rooms (the room in the southwest corner of the synagogue). Here was the community treasury, reached originally through a deep hole in the floor, which was no doubt covered by a stone paver and by a plaited mat over that.

The quantity of gold coins in this hoard makes it the richest coin hoard ever found in an ancient synagogue. The earliest coin in the hoard comes from the Second Temple period, during the reign of Alexander Janneus (103–73 B.C.). But obviously the hoard must be dated to the latest coin, not the earliest. The Alexander Janneus coin was probably an heirloom donated to the treasury at a much later date. Most of the coins come from the late Byzantine period (sixth and seventh centuries A.D.).

A gold dinar (dee-NAHR) of the Abbasid dynasty dates to the year 783 A.D. The latest coin is of the Ayyubid dynasty, from the reign of El-Ottman, in the year 1193. It marks the decline of the Jewish community at Meroth and the latest use of their treasury. Here is clear evidence, together with contemporaneous pottery, that the community was flourishing generations after the Moslems conquered the country. Especially in Upper Galilee, Jewish life seems to have thrived long after the Moslem conquest of 636.

Yet some sudden tragedy must have occurred at the end of the 12th century- Else, why would the community treasury have been left behind? It appears that this large treasury is what remained after the top layer of coins had been hastily removed during a sudden attack on the village. Or perhaps some other manmade catastrophe stopped the villagers from removing the remainder or from returning to collect their money. At this time a frontier between the Ayyubid forces and the Crusaders was being established not far from Meroth. Perhaps a conflict relating to the establishment of this border brought an end to the Jewish community at Meroth. In any event, this coin hoard was left behind, to be discovered by 20th-century archaeologists.

If you would like to visit Meroth, follow the dirt road marked with signs south of the site of ancient Hazor. Tours of the area can be arranged by the staff of the guest house at Kibbutz Ayelet Hashachar. Weekday tours must be approved by the military authorities.

The excavations at Meroth were carried out on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums and the Ministry of Education and Culture and were supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Development. Donations were received from Sol and Diane Colton of Detroit and Stanley H. Burton of Harrgate, England.

The article was written with the assistance of Ze’ev Nitsan. Photographs in this article are published courtesy of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums.

See also-

What’s a Bamah? Beth Alpert Nakhai, BAR 20-03, May-Jun 1994.