Justinian Icons from Sinai, 6th century

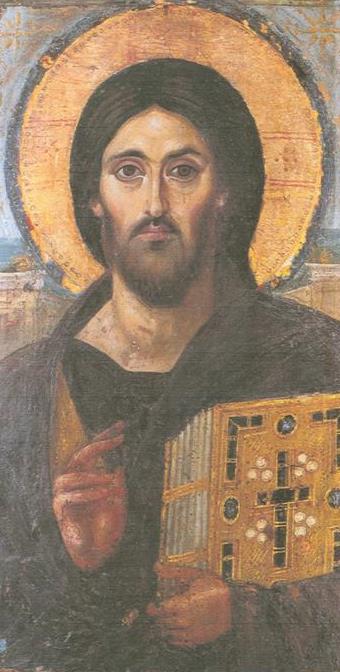

The Blessing Christ, first half of the sixth century. Encaustic on panel. 84 x 45.5 x 1.2 cm (33 1/8 x I7 7/8 x 1/2 in.). The Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine. Sinai, Egypt.

The possibility of proposing personal interpretations is hampered by the lack of inscriptional evidence. Inscriptions were commonly entered onto icons’ frames, but most of the frames are now missing or badly damaged. Besides the panel of Philochristos mentioned earlier, offered perhaps on the occasion of his receiving the monastic habit, only one other early Sinai icon bears an inscription explicitly naming a dedicant, and this is the fragmentary icon of Leo being received by Saint Theodore, who was one of Mary’s military guards in an early icon at Sinai. According to the inscription, Leo is a high government official, a dekanos-that is, a trusted palace messenger. Leo wears a blue mantle with pearled borders and the red shoes of the court (like those of Mary), and his head is framed with the square nimbus of a living person. Because the icon is at Sinai one must suppose Leo’s personal connection with the monastery, such as a visit, more likely on official business from the emperor rather than as a simple pilgrim.

of the court (like those of Mary), and his head is framed with the square nimbus of a living person. Because the icon is at Sinai one must suppose Leo’s personal connection with the monastery, such as a visit, more likely on official business from the emperor rather than as a simple pilgrim.

That the emperor Justinian was personally involved in the monastery is asserted by Procopius, who tells us that Justinian “dedicated” the church he built to the Mother of God, using the language traditional to votive offerings. The site of the Burning Bush, in the garden in front of the monastery, suggests the dedication to Mary as container of God’s fiery presence. That Justinian should also have offered the Enthroned Mother of God icon to celebrate this accomplishment would be most natural . The high quality of the encaustic painting, its generally accepted date in the mid-sixth century, and its “find spot” at the monastery all reinforce this supposition. The icon might be seen to make explicit Justinian’s prayer on behalf of his whole empire.

. The high quality of the encaustic painting, its generally accepted date in the mid-sixth century, and its “find spot” at the monastery all reinforce this supposition. The icon might be seen to make explicit Justinian’s prayer on behalf of his whole empire.

On similar grounds three other icons can be argued to be Justinian’s personal votive offerings- the Blessing Christ (see fig. 50), the Saint Peter, and the Saints Sergius and Bacchus. These, along with the Enthroned Mother and Child discussed earlier, form a fairly tight-knit group assigned to distinguished patronage in Constantinople in the middle of the sixth century. Since its cleaning in 1962, the Blessing Christ has become Sinai’s best-known icon. Its personal association with Justinian is argued most forcefully by Weitzmann, who points out its very close technical association with the Enthroned Mother and Child, down to very minor decorative details such as the tiny punched rosettes in the gold halo. The image type seems to have had a special importance

seems to have had a special importance for the emperor, as it was reused on a silver cross of Justin II (r. 565-78) and on the solidi of Justinian II (r. 685-95). Derived from the facial type of Zeus, the father god of Greece, it was circulated in Egypt on icons of Serapis and Soknebtynis. But the name “Pantocrator” commonly given to its Christian appearance is technically anachronistic; the term is first used in the ninth century, when it refers to the use of this image type in dome decoration. The inscription of “Philanthropos” (Lover of Mankind) above Christ’s right shoulder is later, but it reflects well the benevolent intention of Christ’s blessing gesture. Where the icon was placed when it came to Sinai is not known, but the heavy wear on the lower part of the panel shows that it was available for the devout to greet or kiss it.

for the emperor, as it was reused on a silver cross of Justin II (r. 565-78) and on the solidi of Justinian II (r. 685-95). Derived from the facial type of Zeus, the father god of Greece, it was circulated in Egypt on icons of Serapis and Soknebtynis. But the name “Pantocrator” commonly given to its Christian appearance is technically anachronistic; the term is first used in the ninth century, when it refers to the use of this image type in dome decoration. The inscription of “Philanthropos” (Lover of Mankind) above Christ’s right shoulder is later, but it reflects well the benevolent intention of Christ’s blessing gesture. Where the icon was placed when it came to Sinai is not known, but the heavy wear on the lower part of the panel shows that it was available for the devout to greet or kiss it.

The Saint Peter icon places the saint before a classical niche, like the Blessing Christ and the Enthroned Mother of God, and shares many of their stylistic traits. It may also have a personal connection with Justinian that has not been mentioned before. While it is well known that “Justinian” is the name the emperor assumed when he was made coemperor with his still-reigning uncle, the emperor Justin, his original name, “Petrus Sabbatius,” is seldom referred to. Justinian dedicated the first church he built in Constantinople to his name saint and to Paul. Erected in his private quarters in the palace, it seems to have been intended as a votive offering in celebration of Constantinople’s reconciliation with Rome in 518, in which Justinian played a prominent role. An icon for his name saint would also be perfectly natural. It is the largest of the early icons in the Sinai collection, a gift worthy of the emperor, distinguished, as Kitzinger says, “by the intense, if aristocratically restrained humanity of the saint’s countenance and by the extraordinary refinement of its pictorial technique.” While the three keys in the saint’s hand are commonly taken to refer to papal primacy, curiously enough, in the city of his primacy, namely Rome, Peter carries a scroll instead. In early Christian murals at Bawit, however, keys are an attribute of abbots, entrusted with the administration of their monasteries. Perhaps Peter, as overseer of the universal church, was seen as a suitable model for Longinus, the abbot of Sinai, who is known to us by his robust portrait in the apse of the basilica.

Alongside his church of Saints Peter and Paul, Justinian erected a second church, which, it has been proposed, was another personal votive offering, this time in celebration of the peace treaty he signed with the Persian Empire in 532. This time the saints honored, Sergius and Bacchus, were military officers who had served in the Roman army on the eastern frontier, where they suffered martyrdom. Justinian restored the Syrian city named for Saint Sergius – that is, Sergiopolis; his dedication of a church to the pair in Constantinople signifies his choice of Sergi us and Bacchus as patrons of his eastern border. One might hypothesize that he offered the icon of these two saints as a similar votive at Sinai, to secure the southernmost point in his eastern border through their protection.

Robert S. Nelson and Kristen M. Collins. Icons from Sinai. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2006. pp. 51-52.