BAR Readers to Restore Israelite Village from the Days of the Judges, BAR 5:01, Jan-Feb 1979.

BAR’s Archaeological Preservation Fund has agreed to preserve and restore the site of Izbet Sartah.

BAR’s Archaeological Preservation Fund has agreed to preserve and restore the site of Izbet Sartah.

Many scholars believe Izbet Sartah is Biblical Ebenezer, where the Israelites mustered for a critical battle with the Philistines in the days of the Judges (see 1 Samuel 4). The Israelites lost the battle, and the Ark of the Covenant was captured by the Philistines. This defeat made clear to the Israelites that their loose tribal confederation was inadequate protection against the encroaching Philistines, so the Israelites for the first time placed themselves under an earthly king—Saul of Benjamin (see “An Israelite Village from the Days of the Judges,” BAR 04-03).

Izbet Sartah was recently excavated by a team of archaeologists led by Moshe Kochavi, director of Tel Aviv University’s Institute of Archaeology. The dig was also sponsored by the archaeology department of Bar-Ilan University.

The site is important because of its significance in Biblical history, but it is also important archaeologically. The site was settled in about 1200 B.C. by the Israelites and then abandoned in about 1000 B.C. The Israelites were the first and the last to occupy the site. Because of this, the archaeologists had no need to remove—and thereby destroy—this Israelite level to reach an earlier archaeological period. Nor did later settlers at the site dig into this Israelite level when they laid their foundations or dug storage pits. At Izbet Sartah, the archaeological scene is not complicated by walls upon walls upon walls. It is, therefore, relatively easy for a student to understand.

As a one-period Israelite site from the Early Iron age (1200–1000 B.C.) Izbet Sartah is almost unique. Three thousand years ago, many such Israelite villages no doubt existed. But this is the only one in Israel which has been uncovered by the archaeologist’s spade in this complete and unmarred condition. (The only other site as fully excavated which was limited to Israelite occupation in the Iron Age I period is Tell Masos in Judah, south of Beer-Sheva. See Aharon Kempinski, “Israelite Conquest or Settlement—New Light from Tell Masos,” BAR 02-03.)

Izbet Sartah is important archaeologically also because the oldest Hebrew writing ever discovered was found here—a small sherd inscribed with the Proto-Canaanite alphabet.

The village of Izbet Sartah, or Biblical Ebenezer, is a small site, but it contains all the typical elements which archaeologists associate with early Israelite settlements- a characteristic Israelite four-room house with one broad room and three long narrow rooms leading from it (the middle one of which was probably an unroofed courtyard); a large number of storage pits or silos dug into the ground (in one of these the alphabet was found); and a series of smaller dwellings which circled the site on the edge of the slope, forming a kind of circumvallation wall. The village was not otherwise protected by a city wall.

The four-room house at Izbet Sartah is an excellent and well-preserved example of this Israelite architecture, the elements of which will be easily discernible to the student and visitor after BAR’s restoration. The entrance to this early example of a four-room house is in the corner through one of the outside long rooms. At a later period the four-room houses were entered through the middle room. The basic four-room plan was used by the Israelites, with variations and additions, for many hundreds of years.

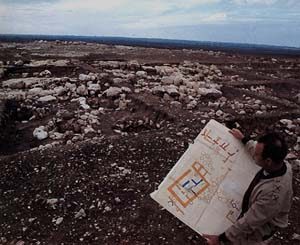

Izbet Sartah also teaches an important geography lesson. It is on the edge of the stony, brown, unfertile hill country occupied by the Israelites. It overlooks the rich, green, well-watered Philistine plain. As Professor Kochavi and BAR Editor Hershel Shanks stood on Izbet Sartah’s stones overlooking the fertile Philistine plain and planning the restoration, Professor Kochavi remarked, “To the Israelites standing here 3000 years ago looking down at all that green below, the Philistine territory must have looked like the Garden of Eden—or perhaps like the Promised Land which the Israelites could not enter. So close and yet so far.”

The preservation and restoration work will be directed by Professor Kochavi and will be completed within one year. It will consist of consolidating and strengthening existing walls, replacing restorable, but missing elements, and removing balks so that the architecture will be clearly revealed. Self-guiding signs will be placed on the site, and a small fund will be set aside for annual maintenance.

The preservation and restoration work will be coordinated for BAR by BAR’s Preservation Liaison Director Georg Majewski. The funds are being provided by BAR’s readers.