Jews in the Hellenistic World

Lawrence H. Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991.

Much more is known about the Jewish communities of the western Diaspora in this period. We have already met the small colony of Jewish troops that was based in Elephantine in Upper Egypt after the Persian conquest in 525 B.C.E. Jews probably first immigrated to Egypt from Judea in the difficult years following the Babylonian conquest in the early sixth century B.C.E., and some Babylonian Jews must have come there in connection with the Persian conquest. Large-scale Jewish emigration from Palestine to Egypt, however, is first attested in the reign of Ptolemy I (323–283 B.C.E.), although accounts differ as to whether the Jews who came to Egypt at this time did so voluntarily or as captives. The Egyptian priest Manetho, in the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.E.), may be credited with being the author of the first known anti-Semitic tract. His writings show familiarity with the exodus and indicate that there were enough Jews in Egypt to make attacking them worthwhile. At the same time, Ptolemy II is credited with having arranged the liberation of many Jews still held captive from his father’s day.

Much more is known about the Jewish communities of the western Diaspora in this period. We have already met the small colony of Jewish troops that was based in Elephantine in Upper Egypt after the Persian conquest in 525 B.C.E. Jews probably first immigrated to Egypt from Judea in the difficult years following the Babylonian conquest in the early sixth century B.C.E., and some Babylonian Jews must have come there in connection with the Persian conquest. Large-scale Jewish emigration from Palestine to Egypt, however, is first attested in the reign of Ptolemy I (323–283 B.C.E.), although accounts differ as to whether the Jews who came to Egypt at this time did so voluntarily or as captives. The Egyptian priest Manetho, in the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.E.), may be credited with being the author of the first known anti-Semitic tract. His writings show familiarity with the exodus and indicate that there were enough Jews in Egypt to make attacking them worthwhile. At the same time, Ptolemy II is credited with having arranged the liberation of many Jews still held captive from his father’s day.

Onias’s role in Egyptian political and military affairs shows the extent to which Jews were already penetrating the life of the country as a whole. As a result of Onias’s support for Cleopatra II, the widow of Ptolemy VI, Ptolemy VII Physcon (145–116 B.C.E., also called Euergetes II) unleashed a pogrom against the Jews, the first such event documented in history. Peace was eventually restored when Ptolemy VII married Cleopatra. Good relations with the Jews must have been quickly restored, since a synagogue was eventually dedicated in his honor.

Onias’s descendants continued to serve in the Ptolemaic military under Cleopatra III (ruled jointly with Ptolemy VIII and IX, 116–102 B.C.E.). His sons Helkias and Hananiah were among her commanders. They are credited with having persuaded the queen to abandon her plan to conquer and annex the territory of the Hasmonean king, Alexander Janneus. Here we see the loyalty of Egyptian Jewry to their coreligionists in Palestine and their support for the Hasmonean dynasty.

Accounts of the remainder of Jewish history in Hellenistic Egypt are scanty, but they reveal the continued role of Jews in Egyptian affairs up to the Roman period. The center of the Egyptian Jewish community was Alexandria, where Jews had settled as early as the beginning of the third century B.C.E. Before long, two of the city’s five quarters were predominantly Jewish and synagogues were scattered everywhere. Jews were also to be found throughout both Upper and Lower Egypt and constituted a substantial and recognizable group within the population. Many of their communities had originally been military colonies.

The earliest reliable evidence for the spread of the Jewish Diaspora to Asia Minor dates from the reign of Antiochus III, who, around 210–205 B.C.E., transferred Jews from Babylonia to the area that is now Turkey to serve as military colonists. By the time of Simon the Hasmonean (142–134 B.C.E.), a circular letter published by the Roman consul regarding the rights of Jews was sent to nine different regions and cities on the mainland of Asia Minor and four Greek islands. Numerous other locales in Asia Minor are mentioned as having Jewish communities in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. By the first century C.E. Jews were to be found in every part of Asia Minor.

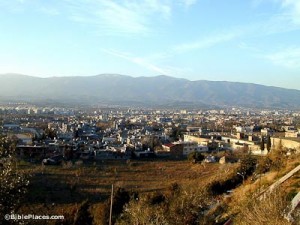

Especially significant in light of its role in the history of the spread of Christianity was the Syrian Diaspora. It size is partly to be accounted for by its proximity to Palestine. The Jewish community of Antioch, Syria’s largest city, was established around 200 B.C.E. Jews dwelled also in Apameia, and in the year 70 C.E. there was a pogrom against the Jews of Damascus. Tyre and Sidon (in present-day Lebanon) were centers of Jewish population from Hasmonean times. By the turn of the era Jews were spread throughout the towns and cities of Syria.

The Jewish community of Cyrene, in North Africa, was founded by immigrants from Egypt in the time of Ptolemy I. The letter from the Roman consul also confirmed the rights of the Cyrenaican Jews. In the mid-second century B.C.E. their number included Jason, the author of a five-volume history which was excerpted in 2 Maccabees. By the first half of the first century B.C.E. the Jews were a distinct population group in Cyrene. The community would continue to grow in Roman times, only to suffer destruction during the revolt of the Diaspora Jews against Trajan in 115–117 C.E.

Jews also settled in Greece, Macedonia, Crete, and Cyprus. The first influx of Jews to Greece may have consisted of captives brought there as slaves during the Maccabean revolt. Presumably many of them remained in Greece after having obtained their freedom. By the second century B.C.E. Greek authors were claiming that Jews were to be found throughout the world. The population figures which they put forward for the Jewish population of Greco-Roman times were vastly exaggerated, but by how much cannot be said precisely.

The size of the Jewish community was no doubt swelled by many proselytes (converts) who were attracted to the ancient Mosaic faith as belief in the traditional deities of the Greek pantheon declined. We cannot be sure what processes of conversion were obligatory in order to join fully the Jewish communities of the Hellenistic world, although there is no question but that circumcision was required. At the same time there was a large class of semi-proselytes who did not formally become part of the Jewish people but kept many Jewish customs, such as attending the synagogues and abstaining from pork. This group of “God-fearers,” as they were called, must have appeared to the pagans to have converted to Judaism, but they did not consider themselves to have become full-fledged members of the Jewish people, nor were they considered by the Jewish people to have become Jews.