Jewish Literature and Culture in the Persian Period (520-332 BCE)

- From Text to Tradition

- Historical Surveys

- Primary Sources

- Nehemiah 8 – The Building of Booths

- Nehemiah 10 – The Oath of the Covenant

- 1 Chronicles 28-9 – The Kingdom of David and Solomon

- Haggai 1 – Rebuilding the House of the Lord

- Haggai 2 – Recalling the Splendor of the First Temple

- Zechariah 3-14 – The Prophecy of Restoration

- Malachi 2-3 – The Last Prophets

- Josephus, Against Apion I, 37-43 – Authenticity of Scripture

- Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 14b-15a – The Order of Scripture

- Mishnah Yadayim 3-5 – The Debate Over the Biblical Canon

- Tosefta Yadayim 2-14 – The Biblical Canon and Divine Inspiration

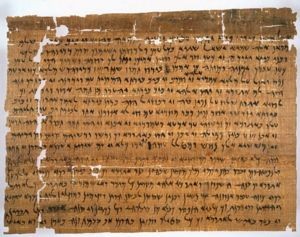

- Elephantine Passover Papyri – The Observance of Passover

- Elephantine Temple Papyrus – The Destruction of the Temple Elephantine

- Secondary Sources

- Images