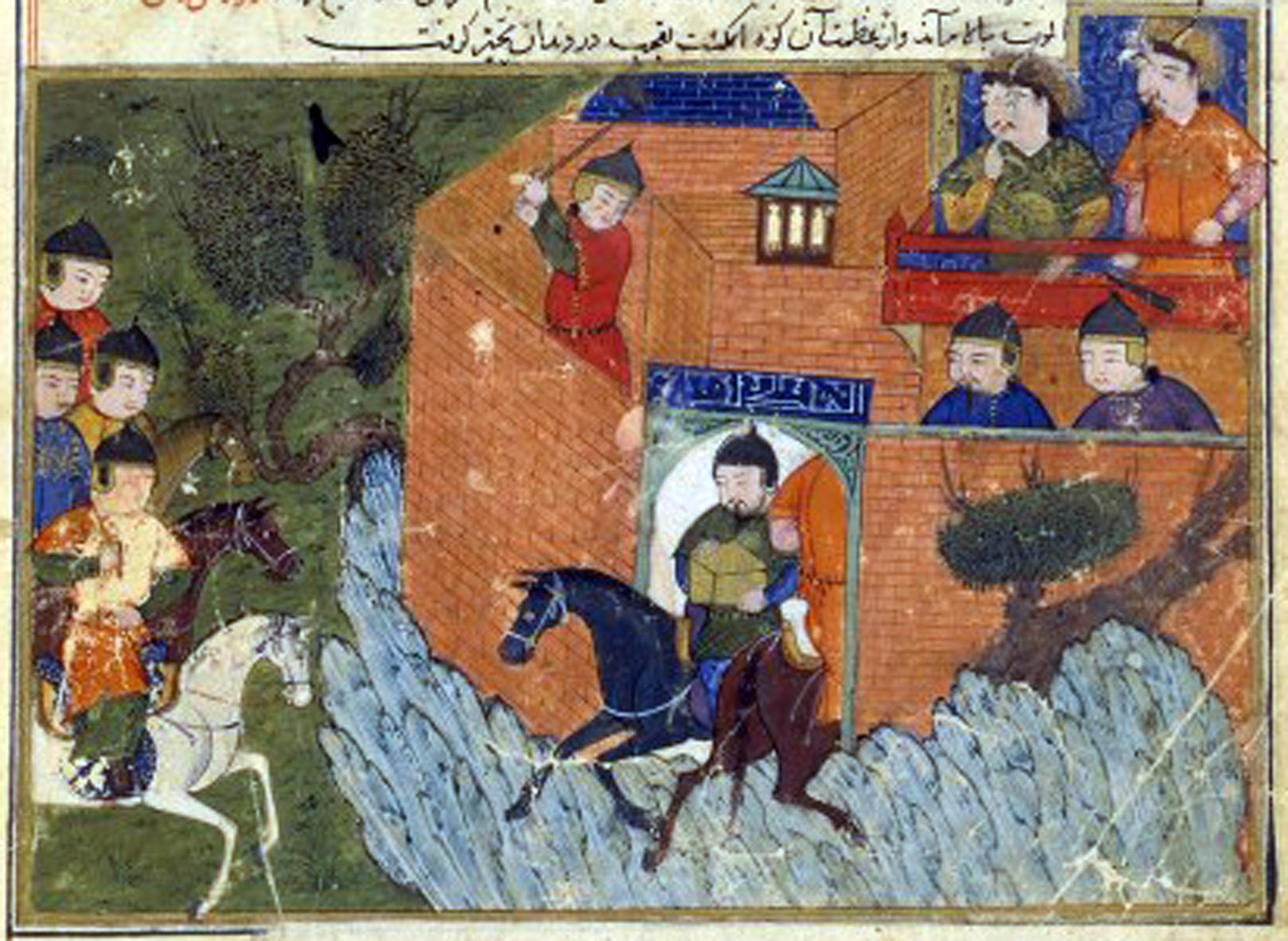

Hulegu Enters Jerusalem, 1260

Hulegu, the son of Genghis Khan and brother of Kubla Khan, entered Jerusalem in 1260.

Hulegu, the son of Genghis Khan and brother of Kubla Khan, entered Jerusalem in 1260.

By comparison with the European campaigns of 1237-1242 the Mongol progress in the Islamic world had been slow but steady, but an important development occurred in 1251 when Hulegu was sent on a military campaign into south-west Asia by his brother Mongke, the newly elected Khan. His overall brief was to subject ‘the Western countries and the various lands of the Sultan’.

The destruction of the Assassins

Hulegu left Mongolia in 1253 and took three years to complete the long journey towards his first objective, which was the headquarters of the Ismailis, a heretical sect of Islam otherwise known as the Assassins from their use of the drug hashish. Their use of murder as a political and religious weapon has meant that the word ‘assassin’ has entered our language in a very different context. This was a particularly challenging operation for the Mongols, because the Assassins were based in a series of castles located on the tops of hills within dry valleys near the Caspian Sea in Iran.

The Mongols used large Chinese-style siege crossbows against them, positioning them on mountain peaks opposite the fortresses to give a horizontal trajectory. The siege crossbow is described by Juvaini as an ‘ox’s bow which had been constructed by Khitan craftsmen and had a range of 2,500 paces’. Teams of ‘athletes’ were stationed about 300 yards apart to transport the frames and poles of the collapsible crossbows up the slopes. Hulegu himself commanded from one of these vantage points-

Arrows, which were the shaft of Doom discharged by the Angel of Death, were let fly against these wretches, passing like hail through the sieve-like clouds.

The Assassins used traction trebuchets and hand-held crossbows against any Mongol attackers climbing up on foot. The Mongols also used large fire arrows loosed from their siege crossbows. This won them more ground, and during peace negotiations the Mongols took advantage of the coming and going of the messengers to find more suitable sites for their catapults and to assemble them undisturbed. The next day a general assault began from these new and greatly advantageous positions. The use of the word ‘mangonels’ in the accounts suggest that traction trebuchets had now been added to the Mongol armoury. The Ismailis took what shelter they could from the dual bombardment, but after some fierce fighting the castles surrendered.

By 1256 Hulegu had completed the first phase of his campaign and could turn his attentions to further Islamic conquests. Most of the rulers of Iran had already made their submission to the Mongols, but one outstanding figure who had not bent the knee was the Caliph of Baghdad. The Caliph may have exercised little real authority beyond that city, but his religious and political influence in the Islamic world was tremendous, and it must have annoyed the Mongols to hear of him proclaiming the same sort of nominal universal sovereignty that the Mongol Khan claimed for himself.

A Mongol army laid siege to Baghdad in 1258 and intimidated the inhabitants by sending arrow letters over the walls, stating that only non-combatants and certain high officials would be spared. We are told that the Mongols were short of catapult projectiles and had to make do with sections cut from palm trees or with stones brought from three or four days’ journey away, but these sufficed to assist in the capture of the eastern wall. Some people tried to escape down the river, but were driven back by a hail of stones and naphtha bombs. When the city was taken the Caliph was put to death.

Even before Baghdad was captured there is evidence that Hulegu already had the idea of pushing on to Syria and Egypt, where they would come into contact with another legendary band of fierce mounted warriors in the form of the Mamluks. The Mamluks were slave soldiers, mostly of Turkish origin, who had been taken from their homes and converted to Islam. They underwent strict military training and fought as mounted archers for their patrons, to whom they maintained a fierce loyalty. Some of these Mamluks owed their origins to earlier Mongol campaigns, and in fact slaves taken from the defeated Polovtsians are believed to have ended up fighting against the Mongols in Syria in 1260.

The Mongol invasion of Syria began with the customary exploratory raid, and then, on 18 December 1259, a Mongol army under Hulegu, together with Georgian, Armenian and Seljuk Rum (Anatolian) troops, crossed the Euphrates and took up positions outside Aleppo. The siege lasted a week, and was followed by the usual slaughter and looting, although Aleppo’s famous citadel held out for a further month. When it eventually fell the building was demolished but, unusually, the defenders were allowed to live. After this success Hulegu marched westwards and took Harim, then returned to Aleppo where he received delegations of dignitaries from Hama and Horns who had come to surrender their cities.

Up to this point the campaign had been a straightforward one. Even before the fall of Aleppo, Hulegu had sent an army under his trusted general Ketbugha on exploratory expeditions to the south. Ketbugha was placed in charge of Syria at Damascus when Hulegu withdrew in 1260, supposedly in response to the news of the death of his brother Mongke Khan. This had led to a succession dispute between his other brothers, Arige-boke and Khubilai. The result was that Syria was left under Mongol control, but only a small army of 10,000 men defended it. Nevertheless, Ketbugha continued to act with the customary Mongol self-confidence, sending a raiding party into Palestine as far as Gaza. Hebron, Jerusalem and Nablus are recorded as being among the other targets. The force was safely back in Damascus by the spring of 1260.

Stephen Turnbull. Genghis Khan & the Mongol Conquests 1190-1400. Osprey Publishing, 2003. pp. 56-59, 62.