Buried Treasure: The Silver Hoard from Dor, Ephraim Stern, BAR 24:04, Jul-Aug 1998.

At first, our discovery—an unadorned clay jar—seemed deceptively modest. For months we had been excavating an area overlooking the southern harbor of ancient Dor, south of Haifa on Israel’s Mediterranean coast. Digging conditions had been particularly arduous. To shield ourselves from the intense daytime heat—temperatures often reached triple digits, especially in the absence of a cool sea breeze—we put up a black gauze screen over the dig squares. Just beyond Dor’s southern harbor, a picturesque beach, frequently filled with bathers, proved tantalizing- Our volunteers were often distracted, longing for a refreshing dip as they perspired under the unforgiving Mediterranean sun.

At first, our discovery—an unadorned clay jar—seemed deceptively modest. For months we had been excavating an area overlooking the southern harbor of ancient Dor, south of Haifa on Israel’s Mediterranean coast. Digging conditions had been particularly arduous. To shield ourselves from the intense daytime heat—temperatures often reached triple digits, especially in the absence of a cool sea breeze—we put up a black gauze screen over the dig squares. Just beyond Dor’s southern harbor, a picturesque beach, frequently filled with bathers, proved tantalizing- Our volunteers were often distracted, longing for a refreshing dip as they perspired under the unforgiving Mediterranean sun.

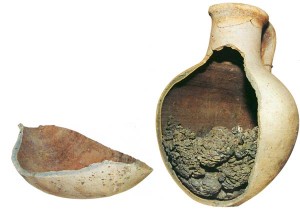

We found the unassuming clay jar at the end of the 1995 excavation season, and though we had no idea what it contained, we decided to leave it in situ until the following year, when we could excavate it in its complete context. Before removing it, we wanted to be sure of the stratigraphy—the stratum, or layer, with which the vessel was associated.

When we returned the following year to complete the excavation of the area around the jar (designated Area D-2),1 we were pleased that we had left the vessel in situ. It had clearly been buried in a pit dug into an ancient floor; it was therefore associated with the floor, not with the layer beneath it. Whoever hid the vessel perhaps anticipated an impending catastrophe and acted with considerable foresight. But he or she never returned to retrieve the vessel—or its contents.

Given these circumstances, it was not surprising that the vessel contained valuables. However, we were not prepared for what we found.

As soon as we lifted the heavy vessel, we knew there was something inside. Whatever it was no longer fit through the small mouth of the jar, so we widened an old break in its side, opening almost an entire side of the vessel. To our amazement, the jar contained a few cloth bags filled with pieces of silver!

The silver weighed approximately 19 pounds (8.5 kilograms), making this one of the largest silver hoards from this period ever found in ancient Palestine. But what exactly was this period?

Indeed, it is its age that makes this silver hoard especially interesting. The structure in which the vessel was found, located between two large buildings once associated with the harbor’s maritime activities, dates to the late 11th or early 10th century B.C.E. In Biblical terms, this corresponds to the end of the period of the Judges. But archaeologically, this period falls in the heart of what is sometimes called the “Dark Age.” Around 1200 B.C.E., soon after the the destruction of the Mycenean palaces on the Greek mainland, the entire Mediterranean region—including Greece, Anatolia, Palestine and Egypt—became destabilized. Civilizations were destroyed and cities devastated. An ethnic group known as the Sea Peoples, of whom the Philistines are the best known, migrated from somewhere in the Aegean to the eastern Mediterranean. One of the Sea Peoples, the Sikils—their name may be etymologically related to Sicily—settled north of the Philistines’ settlements on the eastern Mediterranean coast. It was the Sikils who built the harbor at Dor, one of the oldest harbors in the Mediterranean. According to maritime archaeologist Avner Raban, who has been conducting underwater excavations at the site, “the harbor installations are the first in Palestine that can be definitely attributed to one of the Sea Peoples.”2 Raban has observed the harbor’s many resemblances to harbor installations in Crete (at the Minoan site of Mallia) and in Cyprus (at Kition).

On the tell, we will soon be excavating the town associated with the Sikil-built harbor. We already know that this settlement was destroyed in the mid-11th century B.C.E. or perhaps even a bit earlier. It was soon replaced by a Phoenician town, suggesting that the Phoenicians destroyed the Sikil settlement. The Phoenicians are the people we call Canaanites, who, themselves displaced at about this time, renewed their civilization in the coastal areas of northern Palestine and Syria, soon becoming a maritime people with colonies extending throughout the Mediterranean. The Phoenician city at Dor, however, was destroyed in the early tenth century B.C.E. by the Israelites, under King David.3

The jar containing the silver hoard belonged to a resident of the Phoenician city. It is this city that provides the context for understanding the hoard.

Among other things, the hoard tells us about the uses of money during this very early period—half a millennium before the introduction of coinage—when traders either bartered with each other or made payments with precious metals (gold or silver) measured by weight. Instead of the coin, the shekel was the unit of measure at this time.

Each weighed unit of silver had been placed in a cloth bag that the Bible refers to as a zeror kesef, often translated as “money bag.” In Genesis 42, for example, when Joseph’s brothers come to Egypt for food, Joseph, the governor of the land, recognizes them, but they do not recognize him—he has risen to such a high position. Joseph speaks harshly to his brothers and accuses them of being spies. They are not spies, they protest, but have instead come to Egypt because of a famine in Canaan. They are 12 brothers, one of whom (Benjamin, the youngest) stayed at home with their father; the other, they tell Joseph, was “no more” or “lost” or “gone,” depending on the translation. To test the truth of their story, Joseph holds one of the brothers, Simeon, hostage and tells the others to bring their youngest brother to Egypt. Joseph then orders that bags of grain be sold to the remaining brothers. When the brothers later open their sacks of grain, they find that their money has been returned to them. Upon returning to Canaan, they empty their sacks- “There in each one’s sack was his money-bag!” (New Jewish Publication Society, New American Bible, Genesis 42-35). (The New Revised Standard Version and New Jerusalem Bible translate the phrase as “bag of money.”)

Like those of today, these ancient money bags were probably made of linen.4 Each of the money bags from Dor was of a different weave and density.5 Apparently, they were all woven on a standard warp-weighted loom that was common in the period. We found many such clay loomweights at the site, so it is probable that the cloth of the money bags was woven there.

Each of the linen bags was sealed with a bulla (a lump of clay bearing a seal impression). The same stamp seal was used to impress all of the bullae, indicating that the entire hoard was the property of one person. The seal itself, however, was another surprise. It consists simply of interlocking scrolls and spiral designs. Daphne Ben-Tor of the Israel Museum, who prepared a comprehensive report on these bullae, concluded that the seal impressed on them dates to Middle Bronze II,6 about 1750 B.C.E. That is, the seal is some 700 years older than the linen bags! So-called “heirlooms” are not that unusual when the time span between the date of production and the date of use is relatively short, but in this case the span is several centuries. This suggests that the seal might have been found by chance and cherished for its symbolic significance or simply for its practical shape and interesting engraving. This is not the only time that Middle Bronze seals have been found in first-millennium contexts.7

The Phoenician from Dor who buried the silver hoard divided it into 17 units of weight and placed them into the linen bags. When we found these 17 units, they were stuck together and had to be separated in the laboratories of the Israel Museum. Each of the 17 units weighed a little more than a pound (490.5 grams)—apparently a Phoenician unit of weight, though we don’t know exactly what unit it was. In the eighth to seventh centuries B.C.E., one royal Judahite shekel weighed four ounces (11.5 grams). (We also found a royal Judahite limestone shekel weight at Dor.) Incidentally, the verb shekel, to weigh, is used in all Semitic languages. Although the silver in our clay jar had been divided up into units according to weight, we still could not determine precisely how much a shekel weighed in the 11th and 10th centuries B.C.E. It is possible that the unit examined here was based on a smaller shekel and consisted of 50 shekels, or one mina.8 In that case, the hoard amounts to 17 minas, a formidable sum. (Mina is the usual translation of the Hebrew maneh, of which there are cognates in Sumerian, Akkadian and Ugaritic.)9

Other excavations have uncovered a number of silver hoards, but these consist mostly of broken pieces of jewelry. Ours is different. Only a small portion of our find consists of broken jewelry. Most of the hoard is made up of small, flat tokens cast in the shape of small coins, as well as other pieces of cut silver sometimes referred to as hocksilber.

In short, this was a hoard of an early form of money, that is, silver weighted for payment. It probably belonged to a Phoenician merchant, who would have used the money to build and equip seagoing ships or to buy merchandise to be later traded in lands to the west.

We submitted several specimens from this hoard to the laboratories of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, to determine the possible origin of the silver. Analysis showed that the silver contains a gold content of no less than 11 percent.10 During the 11th and 10th centuries B.C.E., silver with a similar gold content was mined at Rio Tinto, in Spain. Some scholars have speculated that the early Phoenicians expanded westward primarily to obtain silver from Iberia. As Samuel Wolff of the Israel Antiquities Authority has noted, “The archaeological evidence at Rio Tinto and Castulo (east of Rio Tinto) indicates that both sites, located in the most important silver production zones in ancient Iberia, had relations with the Phoenicians and Carthaginians.”11 The silver from Dor, therefore, may have originated in Iberia. But the significant presence of gold in the silver’s molecular makeup could have resulted had the silver been recast.

We know less about the other silver hoards discovered in Palestine because of the inferior technologies available at the time they were found. A similar cache, consisting mostly of broken pieces of jewelry, was found in the 1930s at nearby Megiddo in Stratum VIA, which is generally dated to the 11th century B.C.E. It, too, was divided into weighted units (three of them) wrapped in cloth.12

In the early years of this century, a hoard of 26 units of silver was uncovered at Gezer. The excavator, R.A.S. Macalister, dated it to the early Israelite period,13 but we know little else about it.

A tenth-century B.C.E. hoard (as dated by its excavator, Yohanon Aharoni) was uncovered at Arad. Like the Dor hoard, the Arad silver was divided into units and placed in a jug, each unit having been wrapped in cloth and subsequently buried.14 Unlike our hoard, however, it consisted mostly of broken pieces of jewelry.

The largest silver hoard found in ancient Palestine, probably from the tenth century B.C.E., was discovered at Eshtemoa.15 It was concealed in five jugs and included pieces of broken jewelry and units of silver.16 It weighed more than 60 pounds.a

To understand the broader significance of our silver hoard, we must place it in a wider context.

The pottery associated with it included a beautiful assemblage of Phoenician Bichrome Ware, typical of the early stages of Phoenician material culture. These vessels were probably made at production centers in Tyre or Sidon and shipped south. From the same stratum we also found significant sherds of imported Cypriot ware. These Cypriot sherds, which can be very securely dated to the late 11th or early 10th century B.C.E., provide evidence that the Phoenicians at Dor traded with Cyprus. Thus we can date the Phoenician pottery—and our silver hoard—to this period. We even found some Greek pottery imported by Dor’s Phoenician merchants.

What all this suggests is that even at this early time, maritime trade with the west had already been renewed. In short, the so-called Dark Age did not last as long as had previously been supposed. A new day was already dawning.

a. See Ze’ev Yeivin, “The Mysterious Silver Hoard from Eshtemoa,” BAR 13-06.

1. Area D-2 was supervised by Ayelet Gilboa and Benjamin Avenberg.

2. Avner Raban, “The Harbor of the Sea Peoples at Dor,” Biblical Archaeologist 50 (1987), pp. 118–126.

3. Raban, “Sea Peoples.”

4. The cloth was analyzed by Carmela Shimoni of the Israeli Fiber Institute in Jerusalem.

5. The weaves were identified by Avigail Shefer.

6. According to Daphne Ben-Tor, “Interlocking scrolls and spiral designs are common on scarabs found at Middle Bronze Age Canaanite sites … The design found on the Dor bullae is also typical of Middle Kingdom-Middle Bronze Age patterns not found on other scarabs. A close parallel to the patterns occurring on the Dor bullae [is] found on Middle Bronze Age scarabs from Megiddo.” We may add that this same pattern occurs on scarabs from Dor and from nearby Tel Mevorakh in this same period.

7. Middle Bronze scarabs have been found in first-millennium contexts in Ibiza and Sicily. Indeed, a Middle Bronze Age scarab was recently found in a Late Roman tomb dating to the third to fourth centuries C.E. at Moza ‘Illit in Israel.

8. Ephraim Stern, “Weights and Measures,” Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem- Keter, 1971), vol. 16, cols. 375–392.

9. For further discussion of the mina, see Stern, “Weights and Measures.”

10. The report, “Analysis by Atomic Absorption,” is by Nimrod Shay and Maurice Fontain.

11. Samuel Wolff, “Maritime Trade at Punic Carthage” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1986).

12. Gordon Loud, Megiddo II (Chicago- Oriental Institute, 1948), pl. 229-24.

13. R.A.S. Macalister, The Excavations of Gezer (London- Palestine Exploration Fund, 1912), vol. 2, p. 262, fig. 408.

14. See Yohanan Aharoni, “Arad,” Revue biblique 75 (1968); and Miriam Aharoni, “A Hoard of Silver from Arad,” Qadmoniot (1980), pp. 39–40.

15. Ze’ev Yeivin, “The Silver Hoard from Eshtemo’a,” Atiqot, Hebrew Ser., vol. 10 (1990), pp. 43–57.

16. On three of the jugs, the Hebrew word hamesh (five) was written in red paint. The contents of one jug, found intact, weighed about 1 pound. As with the hoard found at Dor, it contained silver tokens, jewelry and some pieces of cut silver. Yigael Yadin thought that these five containers and the inscription “five” represented 500 shekels. The problem with this suggestion is that their weight does not correspond to the late Judahite shekel of 11.5 grams. Perhaps the shekel of this period, like ours, followed a different standard; if so, it was probably a lighter shekel. See E. Eran, “A Metrological Consideration of the Eshtemo’a Hoard,” ‘Atiqot, Hebrew ser., vol. 10 (1990), pp. 58–60.