Excerpts from James Parkes, The Emergence of the Jewish Problem: 1878-1939, Oxford University Press, London 1946.

By the nineteenth century more than half the Jewish populations of the world lived in the western provinces of Russia, with an overflow in the northern provinces of Austria-Hungary and Rumania. Russian Jewry was a vast artificial accumulation still living under restricted, inhuman conditions. It had become Russian, not through any desire of Russia to possess Jews, but as a consequence of the partition of Poland, and of Russia’s other acquisitions in the south-west of her territory. Except to a chosen few in the liberal professions or among the wealthier provinces to this vast Jewish population; and within the Pale of Settlement they had all the duties and none of the privileges of citizenship…

p. xix-xx

Assimilation vs. Nationalism

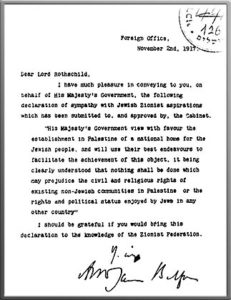

The first comers feared rather than admired the busy Western world around them. They settled in compact masses; they often lived for years without acquiring more than a few words of the language, and the majority made little attempt to acquire naturalization in their new country. But as time went on a new ideal appeared among the eastern Jews, both in Eastern Europe and in the countries of the West where they had settled, the idea of Jewish nationhood, and of the right, indeed the need, of Jews to be Jews, not just Israelite citizens of England, France or the United States. By the time this idea had spread to the West there existed a generation, educated in the schools of their new country, familiar with its language and imbued increasingly with political traditions and ideas. Hence arose a conflict between assimilation and nationalism which has torn Jewry ever since. The embodiment of the national idea in Zionism, and its recognition by the Balfour

Declaration, made the conflict more bitter, even though the events from 1933 onwards have made many assimilated Jews accept the value of the National Home as a place for the settlement of refugees.

p. xxii-xxiii

The Wording of the Balfour Declaration

Zionist opinion, when the probable wording of the Declaration was made known to them, pressed for the phrase ‘the establishment of Palestine as the National Home’. The phrase finally adopted, ‘the establishment in Palestine of a National Home’, expressed approval of a much more moderate programme. In words it recognises no more than the rights of the Jews to share the country with others, and leaves the political character and future development of the National Home completely obscure. But the Arabs on their side criticize the latter because they are referred to simply as existing non-Jewish communities, and only their civil and religious rights are assured. It is in fact a document which, rather vaguely, promises to assist an undefined situation to emerge, and says as little as possible as to what possible consequences may be for any of the parties involved.

p. 11

British Ambitions in Palestine

British ambitions in Syria, as revealed in the Sykes-Picot Agreement, were modest and openly strategic. They wanted to occupy the port area of Acre-Haifa, and to ensure that the Government of the Sanjak of Jerusalem could not entertain hostile intentions against the Suez Canal. There is no sign at that date (1916) of their wanting themselves to control the Government of Palestine. Nor does the Balfour Declaration explicitly necessitate that they should do so. The reconstruction of a separate Palestine with approximately its Biblical frontiers, and the translation of an international into a British administration, seem to have been almost an accidental by-product of the system, and of the pressure of the Zionist Organization.

p. 21

Illegal Immigration

Finally, in spite of their loyalty, in spite of their overwhelming need, the door was slammed in their faces. Pitiful shiploads of hunted fugitives, coming to Palestine as a last resort, were brutally turned away. Some sank with tragic loss of life. The British Government, which had yielded to almost everyone else in the world, was adamant where these unhappy victims of persecution were concerned. Those who succeeded in landing were, if caught, hustled into detention camps, and their numbers were deducted from the immigration schedules. The whole magnificent vision of a National Home, built by their own efforts and entirely by their own resources, was imperiled, even destroyed, by the blindness and lack of imagination of the Power with whom they most desired to be friends and to whom they were certain that they could be invaluable allies.

p. 30

Herbert Samuel’s Legacy

While there is nothing in the Mandate to conciliate Arab feelings the mere fact that a decision had been taken, and that the constitution of the country was now established, must have made many Arabs feel that the game was lost, and that it would be wisest to make the best of things. It was a number of years before the extremists again felt sufficiently powerful to menace public security; but they obtained the rejection of the Legislative Council proposed in 1923, and official Arab co-operation with the Government was withheld thereafter. The Arab members of the existing Advisory Council resigned, and the Government was unable to replace them. Yet an Arab Moderate Party came on the scene, and the extremists did not hold a Congress between 1923 and 1927. Thus it was not unnatural that Sir Herbert Samuel, on retiring from office in 1925, should have been able to give an optimistic picture of the country, and to have felt that the worst was now over and that the actual impartiality of the Administration, together with the visible evidence of the good intentions of the Zionists, had dispelled the exaggerated feelings of the Arabs in the earlier days. But together with a good administration Samuel had unwittingly bequeathed to his successors the Administration’s greatest enemy – Haj Amin el Husseini, whom he had appointed Mufti of Jerusalem in 1922. Haj Amin had been convicted of inciting the Arabs to riot in 1921; he was at the centre of the disturbances in 1929 and from 1933 onwards.

p. 46

Nazism and Palestine Immigration

In November 1938 the murder of vom Rath, a Nazi official in Paris, had led to appalling pogroms and to a violent renewal of Jewish persecution in Germany. It was not surprising that the only practical question which interested the Zionists was the number of Jews, adult and children, who could be saved from the Nazi hell. This feeling was shared by many English political leaders, and a Parliamentary debate on Palestine in December 1938 witnessed many fervent appeals from Christian leaders to the Government, urging on them a generous immigration policy. But the Government had also to consider its relations with the Arabs, and the Arabs were clamouring for a complete cessation of immigration.

p. 58-59

The Balfour Declaration and Violence in Palestine

…the disappointment of the Jews and dissatisfaction of the Arabs are alike the natural and inevitable result of the entangling contradictions of policy in which the British Government involved itself during and after the first world war. In this picture the Jewish National Home constantly appears as something embarrassing and almost exotic in the atmosphere of the Middle East. It would be easy to claim – in fact it is often claimed – that all our difficulties in Palestine arise from our weakness in carrying out an international obligation, the Balfour Declaration. But both claims ignore the fact that the French have had still more serious trouble without any such complications as the constant arrival of Jewish immigrants on the one hand or an unwillingness to meet violence with immediate violence on the other.

p. 66

Labour

Twenty years is a very short period in the life of a nation and time will bring many changes to the structure of the National Home, as well as a certain stability and maturity it could not yet be expected to possess. But the main structure of a community is there already, and it differs from any Jewish society elsewhere. It is curious that it should be a matter of boasting that in Tel Aviv there are Jewish street scavengers as well as a Jewish mayor, that Jews occupied with the building industry in Palestine do not merely design, construct, or decorate the houses, but they actually hew the stone in the quarries, grind the cement in the factories, and make the road to the houses. But a knowledge of the structure of Jewish life elsewhere makes it not only natural but proper that this pride should be there. At the same time the National Home retains essential Jewish characteristics in the intellectual and cultural field. Palestinian music, drama, and cultural life show that the immigrants have no intention of turning their backs on the positive achievements of Jewish life in Europe or America.

The success of the adventure will depend much on the extent to which these two qualities will be maintained when the Home achieves a maturity. Circumstances are likely to prevent its becoming a primarily agricultural or rural community, but it would lose more than occupations for some tens of thousands of Jews if Jewish agriculture dwindled. It is likely to develop a strong industrial and commercial side, but again it would lose if this came to built on Arab and Asiatic labour in the manual and lower-paid grades. And on the other hand, it would lose it the return to manual labour in agriculture and industry meant a loss of cultural and social vitality. It is on this ability to hold on to both that the significance of Palestine to the Jewish people as a whole depends.

p. 85-86

The Structure of the Jewish Society in Palestine

Finally, it may be said that there is a real sense in which the National Home is the outcome of a millennial Jewish tradition. The claim so frequently made that antisemitism is due entirely to the Dispersion is exaggerated; the belief that a National Home will automatically secure the fair treatment of Jews everywhere is naïve optimism. But the essence itself of Rabbinic Judaism is so closely interwoven with the idea of the community; the practical implications of the meaning of social justice, of neighborliness, of mutual help, have filled so many pages of Rabbinic discussion, that it is good that there should be a field in which this long training should find actual expression. It is no question of reconstructing in Palestine the community of the Books of the Law or of the Talmud; but their principles and their spirit are expressed in the social activities of the Histadruth, the Agency, and other bodies in forms which are visibly modern as they are invisibly traditional. It is the ability to blend together innovation and tradition which gives stability and vitality to a nation, and their long exile had denied this ability to the Jews as a corporate group.

It may well be that, if they can once find a satisfactory adjustment of their relations with the Arab world, the final justification of the National Home as a nation among the nations of the world will be that it gives an example of that flexible yet planned society, that balance of liberty and order, which at present we associate with Moses and the prophets and with the people of Israel three thousand years ago, rather than with their modern successors.

p. 87-88

The Congress of Berlin, 1878

Largely owing to the pressure of Jewish organisations and individuals, the Congress, which proposed to recognize the Rumanain principality as a kingdom entirely independent of Turkish nominal suzerainty, attempted to make this recognition dependent on the immediate grant of civic and political equality to all Jews born in Rumania…The Rumanian Government evaded the acceptance of this direct demand by agreeing to introduce a law for the naturalization of its Jewish subjects. But this law, when introduced, compelled each individual to obtain a separate act of Parliament for his naturalization, unless he belonged to a very small category, such as that of combatant in the war of independence. But even most of the 833 individuals in this category failed, in fact, to secure their naturalization. For this there was no justification whatever.

p. 100-101

The U.S. Objects to Russia’s Treatment of Jews

The United States was the only country which had had the courage to attempt officially to tackle Russia’s treatment in the territories of her Jewish subjects. The opportunity arose out of the commercial treaty of 1839 between the two countries, which guaranteed to the subjects of either equal treatment in the territories of the other. Great Britain made a similar treaty in 1869 but, when a British Jew was subjected to humiliating treatment in Moscow in 1912, the British Government refused to intervene, on the ground that the treaty was to be interpreted as meaning treatment equal to that accorded to Russian subjects of a similar category, so that an English Jew in Russian could not claim exemption from restrictions imposed on Russian Jews. This interpretation of the treaty the British Foreign Office maintained up to 1917. The United States adopted the opposite principle, and claimed that an American passport guaranteed the bearer, whatever his race, rights equal to those granted to full Russian citizens; and the State Department refused to tolerate the idea that a foreign Government could discriminate between one citizen of the United States and another. Russia refused to accept this interpretation; and feeling in the United States ran so high at this insult to the American passport that in 1911 President Theodore Roosevelt denounce the treaty rather than accept an interpretation similar to that of the British Foreign Office.

p. 105

Partial Emancipation of the Jews of Rumania

While, in the event, the Russian Revolution saved the Allies from the embarrassment of Imperial Russia’s intentions – or lack of intentions – towards her Jewish subjects, the German conquest of Rumania, and the Treaty of Bucharest signed on 7 May 1918, could not be ignored. For Articles 27 and 28 of that Treaty contained provisions for the immediate grant of full political equality to all Jews who had fought in the war, or who were born of parents themselves born in Rumania – a partial emancipation indeed, but considerably more than had been secured by precious international intervention.

p. 107

Nationalism

In the early days of interest in nationality in eastern Europe it is not surprising if Jews were relatively unaffected. The recognition of a nationality was considered to imply territory and the ultimate ambition to make that territory into an autonomous or sovereign State. It was not until the very end of the nineteenth century that a new idea was put forward in Austria, that nationality was an affair of personal interest not of geography, so that a group of people geographically scattered might form a nationality by the simple fact of their common interest. At this point nationalism, as a political movement, linked itself on to a growing consciousness of their special needs among the Jewish pioneers of the proletarian and revolutionary movements in Russia.

p. 108

The Polish Reaction to the Minority Treaty (1919)

In a memorandum of 16 June, the Polish Government began with a bitter attack on the whole idea of a unilaterally imposed Treaty, on the grounds that it was both an infringement of Poland’s sovereignty, and an impugning of her good faith and the sincerity of her intentions. Further, some of its articles, which was supposed to embody in her constitution, were merely administrative by-laws such as no State should have to accept from outside, or allow only an outside authority to change. Proceeding to attack the Jewish section explicitly, Poland asserted that the present trouble was due entirely to the doubtful loyalty of the Jews. Once the Jews accepted the existence of Poland and their duties in the new Polish State, relations would again become amicable, as they had been for centuries of Polish history. Moreover the Jews themselves were not agreed as to the rights they desired, and many would resent being bound by the Jewish clauses, since they considered themselves Poles…In particular to allow a minority to complain to an outside Power, instead of encouraging it to seek peace within the frontiers of the State in which it was living, would create and not solve problems.

p. 124-125

Obstacles to Jewish Equality in Poland

The grant of individual political equality would have solved the problem if on both sides any immediate possibility of assimilation had existed. The statistics given show that it had certainly not yet taken place in economic or social spheres, and the same was true in the psychological sphere. For the attitude of Poles to Jews had been changing for a decade before the war from a tolerant contempt to an active resentment, which the events of the war had inevitably accentuated. These facts destroyed conditions for successful assimilation on the Polish side. On the Jewish side also it was evident that the spread of the national idea among the masses – whether in Zionist or Socialist form – had led them to reject assimilation entirely.

p. 134-135

…In 1934…new regulations for the artisanate threw hundreds of Jews of work. This was followed by a more unilateral repudiation of the supervision by the League of the Polish Minorities Treaty.

The vicious circle of Jewish disillusion and Polish suspicion began to operate again. The less justice the Jews received, the more enthusiasm they were apparently expected by the Nationalists to show. In June 1935, a month after the death of the Marshal, Nazi demonstrations in Danzig led to tremendous excitement in Poland, and even to the expectation of war. The fact that the Jews did not appear to share the general excitement was at once used by the Nationaliss to accuse them of disloyalty.

p. 139

The Jewish Problem in Poland

The dominant factor about the Jewish problem in Poland was that it was a problem which the Pole was never able to ignore or to forget. In no city, great or small (except in the ex-German west) was he ever able to forget the presence of Jews. Whatever his status in the social order, whatever his profession, he was aware of Jews, not merely as a fact, but as a problem. Again and again conversations with Poles who were in no sense unenlightened would end with the despairing words- ‘What on earth can we do? They are three million!’ Many Poles, probably the majority, were not to the end ‘antisemitic’ in the German sense, but they were oppressed with the hopelessness of finding any solution to the question.

p. 151

Ritual Slaughter

In the last years of the [Polish] Republic a new threat to Jewish economic life was launched in an attack on Jewish ritual killing (Shechita), and a Bill was passed limiting the work of Jewish butchers to the Jewish community. The effect of this was to throw thousands of Jewish butchers out of work, for a large proportion of the general trade had previously been in their hands, and their clientele had included many of the Christian population. It was even planned by successive stages to stop the Jewish method of slaughter altogether by 1941, but the German invasion intervened.

p. 161

The Effects of the Bolshevik Revolution on the Jewish Community

The Jews were emancipated by the Kerensky Government on 16 March (3 April) 1917, and all the disabilities imposed on them by the Tsarist regime were swept away at a single stroke. The result was a period of feverish political and cultural activity, hampered though it inevitably was by the confusion reigning in the country. The Zionists planned the calling of a world conference in order to put forwards their claims to Palestine in the post-war settlement; the Bund made plans for the exercise of their cultural autonomy.

p. 177

A declaration of 15 November 1917 proclaimed the equality and sovereignty of all those who were recognized as separate peoples within Russian territory, abolished all national and religious discrimination, and extended to all national minorities and ethnical groups the right to free development. Under this proclamation the Jews later enjoyed their right to Jewish soviets in districts where the bulk of the population were Jewish, i.e. Yiddish-speaking, for it was as an ethnico-linguistic minority that the Jews enjoyed their privileges in the Soviet Union.

p. 178

The work of actually converting the Jewish population to Communism was undertaken…by the establishment of a Jewish Section of the Communist Party (Yevsektia).

This Jewish Section of the Party was responsible for such persecution as the Jews suffered as Jews at the hands of the new regime. With the special dualism between Party and Government which exists in the Soviet Union, the Yevsektia exercised considerable power and carried on a ruthless war on two fronts – the religious and the Zionist. In both fields it was more ruthless, as well as more efficient, than corresponding non-Jewish Communist bodies…

The battle on the Zionist front was carried on at two different periods. The Zionists were, at first, doubly suspected both as nationalists of a bourgeois type, and as tools of British imperialism in the Middle East. Hebrew was suppressed, as not being a ‘national’ language in the Socialist sense. Zionist organizations were closed, emigration to Palestine was strictly forbidden…

p. 179-180

The Communist Expectation that the Jews Would Disappear

It was the opinion of the successive spokesmen of Communism, Marx, Lenin, and Stalin, that in a Socialist State the Jews, lacking any geographical basis for their national life, would disappear. Stalin, to whom the task fell of putting into practice Communist theory, was perfectly willing to allow Jewish life to survive as long as Jews themselves wished it…But while Jews have advanced – officially – from a number of small soviets to the full status of a nationality, in fact separate Jewishness is steadily and even rapidly declining, and the expectations of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin are proving correct.

p. 189

Modern Anti-Semitism

Modern antisemitism is a political weapon deliberately invented and artificially developed for ends which have nothing to do with the Jewish people or the Jewish religion. Its salient characteristic is that the material out of which it is forged is not only false, but known by its artificers to be false. The actual problems, prejudices, difficulties, and jealousies which arise of the presence of actual Jewish communities are too diverse and too diffuse to have any practical value as a general weapon of the kind which antisemites desired. They had, however, this essential value. They provided the background of susceptibility on which the anti-Semite was able to paint his vast chimeras, and gave the most improbable creations of his fancy the similitude of probability.

p. 195

The Anti-Semitic Message

In order that the widespread public attention which alone will secure votes at the polls for any democratic party could be concentrated on the small groups of Jews who were numerically lost among the mass of the population, four steps had to be taken.

It was necessary to exaggerate their power constantly in order to give plausibility to the idea that they were the enemy of whatever cause the antisemites were advocating. For this purpose the vast financial power wielded during the first half of the century by the House of Rothschild was the foundation on which were evolved fantastic stories of Jewish ‘monopolies’ and the Jewish control of the world’s government.

It was necessary to draw a picture of Jewish unity, in order that it might appear reasonable to attack any Jew in any capacity, rather than to admit that Jews in any profession – including the criminal profession – could only be attacked as part of an attack on that profession, or Jews of any country as part of an attack on the population of that country, and that in both cases Jews who were of another profession or another country were out of the picture. The general, non-political concern of Jews with their persecuted co-religionists had to be presented as part of a common political plot. The politico-philanthropic activities of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, and later the colonizing schemes of the Zionist Organization, had to be presented as part of a world-wide political activity aiming at Jewish domination. The ‘clannishness’ of Jews, arising naturally out of their social and economic isolation, had to be turned into a secret conspiracy.

It was necessary to establish a clear division, Jews one side, non-Jews the other. This task was undertaken by both the clerical and the philosophical enthusiasts of the antisemitic movement, and scandalous misrepresentations of the Talmud poured from the ‘Christian’ the presses with the same velocity as new doctrines of ‘race’ poured from the presses of the universities. The admission that there were ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Jews would have been fatal to the movement, as would have been the admission that a ‘bad’ Jew had it in his power to become a ‘good’ one. Hence while clerical antisemites have not wholly desisted from their activities up to the present time, the racialists have tended to become more important. For it might be possible for a Jew to change his religion to the embarrassment of the former; but it is clearly impossible for him to confute the latter by altering his heredity.

Finally, ‘the Jews’ already presented as immensely powerful, absolutely united, and unalterably different, had to be shown to be deliberately planning the most sinister enslavements of the immense non-Jewish majorities amongst whom they lived. The ‘Jewish world plot’ was the keystone of the antisemitic arch, the final plank in the antisemitic platform; for it allowed for a common danger, equally menacing to all non-Jews, whatever their class, nationality, or political opinions.

It made it possible for antisemitism to become a world-wide institution.

p. 199-200

The Dreyfus Affair

In 1894 the campaign culminated in the condemnation of a French staff officer, Alfred Dreyfus, for treason – because Dreyfus happened to be a Jew.

There were incidents in the trial and condemnation of Dreyfus which led a small minority of the Left Wing Republicans to doubt his guilt, or at least to doubt the validity of his trial, and these doubts were expressed openly. The clericals at once saw what appeared to them a magnificent opportunity to resume the attack on the Republic, which they had concealed rather than abandoned at the exhortation of the Vatican. Instead of having to defend the political and educational pretensions of the church, they could appear as the defenders of the honour of the Army, which by regular court martial had convicted Dreyfus of his crime. The Army occupied a pecurliarly venerated place in French hearts after the defeat of 1870, for the French had never really abandoned the hope of recovering Alsace and Lorraine. Since the Panama scandal, and the popularity of La France Juive, had drawn unpleasant attention to the ‘power of the Jew’, no combination could have appeared more favorable than that of the defence of the Army, and the exposure of the Jews.

Unfortunately for them Dreyfus was totally innocent of his supposed crimes.

p. 210-211

Anti-Semitism after 1919

The period following the war of 1914-1918 witnessed an immense extension of the use of antisemitism as a political weapon, but there was a change in the objectives for which it was used. The religious aspect, which had been especially conspicuous in the activities of political Roman Catholics during the first period, passed almost entirely into the background. The racial aspect assumed a new prominence based on the increase of nationalism, and a further use of it was made possible by the identification of the Jews with the ‘Bolsheviks’…

For a brief period in 1919-1921 two interlocked factors seemed to be going to provide an alarming amount of fresh material of which antisemitism might make dangerous use. The first was the prominence of Jews at the time of the Peace Settlement and the varied forms which that prominence assumed. The second was the publication throughout the world of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

In the Peace Settlement the Nationalistic element among the Jews secured by the Balfour Declaration the establishment of a National Home in Palestine, a project which was commonly believed at that time to be likely to lead to the rapid establishment of a Jewish State under British protection. At the same time the (mainly non-Zionist) Jewish organizations of the United States and western Europe secured from the peace-makers of Versailles the guarantee of complete political and social equality, together with certain separate rights as ‘minorities’, in those countries from the Baltic to the Black Sea in which, before the war, Jews had not possessed equal rights with the rest of the population; and it was no secret that these treaties had been imposed by the Great Powers on both Poland and Rumania (the two countries of most importance from the Jewish point of view) with extreme difficulty, and in the face of vigorous opposition. Finally, in relatively leading positions in a number of national delegations were individual Jews who were supposed to possess considerable power behind the scenes.

p. 216

Nazi Threats

The very violence and fantasy of Nazi anti-Jewish propaganda convince the majority of foreigners, as well as the majority of German Jews, that Hitler’s bark was much worse than his bite. He demanded so complete an elimination of Jews from German life, his threats as to what the Nazis would do when they were in power were so barbarous, that men could not believe that in the twentieth century such persecution was really intended. Even at the beginning of 1933 there were still many of both classes who persisted in remaining blind to the inevitable consequence of the fact that, whatever may have been the motive of his followers, that of the Fuhrer was a conviction that he had a ‘divine’ mission to purge the world of the Jews. And a divine mission allows of no trifling.

p. 222

Lessons

To some extent the distinction between the antisemitism which aims at persecuting the Jews, and that which uses the Jews for other objectives, is an artificial one. But it is justifiable in that it brings two points into the open. One is that antisemitism only takes root, with all its absurdities, because there actually are unsolved problems connected with the world situation of the Jews. The non-existent Jew of antisemitic propaganda carries conviction because it can be tied up with actual abnormalities in the position of the Jews, and with ancient prejudices and superstitions in the mind of non-Jews. The other lesson is that antisemitism is a most potent weapon against society as a whole. Hitler was making no mistake when he seized on it as the easiest and most effective way of undermining the unity and strength of his opponents.

p. 229

The Solution

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the only satisfactory solution from the Jewish point of view is one which makes it possible for those who desire it to go to Palestine…So far as the Jews and Jewish needs are concerned, the argument in favour of allowing them room to develop, and the complete control over their own future, is overwhelming. Were the country otherwise empty, nobody would question it. But the country is not empty, and the resulting conflict of interest is one which will need the most serious attention, and the most courageous and generous action, of the peacemakers. I do not believe it can be settled by a balancing of legal rights and promises. A new standard of judgment is required – and that not in this question only. If the twentieth century is to become the century of the common man, I suggest that the new basis is the practical basis of need.