Kingdoms of Judah and Israel, 1000–586 BCE

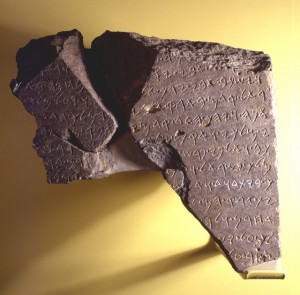

The “House of David” Inscribed on a Victory stele, Tell Dan, Basalt, Israelite period, 9th c. BCE, H. 32 cm, W. 22 cm, IAA 96-125/ 93-3162

Highlights-

- Gezer Calendar, 10th century BCE

- Public Building in the City of David, 10th century BCE

- King David, 1005-965 BCE

- Relief and Stelae of Pharaoh Shoshenq I- Rehoboam’s Tribute, c. 925 BCE

- Seal of Jezebel, 9th–8th century BCE

- Kurkh Stele, 853 BCE

- Moabite Stone, c. 840 BCE

- Tel Dan Stele, c. 840 BCE

- Annals Edition 4 – The Black Obelisk, 828 or 827 BCE

- Isaiah Through The Ages, 8th century BCE

- Tel Al Rimah Stele, 797 BCE

- Iran Stele, 737 BCE

- Tiglath-Pileser III and the Syro-Ephraimite War- Kalah Palace Summary Inscription, 729 BCE

- The Babylonian Chronicle, 722 BCE

- The Nimrud Prism, 720 BCE

- Hezekiah’s (or Siloam) Tunnel Inscription, 701 BCE

- Hezekiah’s Defeat- The Annals of Sennacherib on the Taylor, Jerusalem, and Oriental Institute Prisms, 700 BCE

- Lakhish Reliefs at Nineveh, c. 700 BCE

- Silver Scroll Amulets from Ketef Hinnom, c. 600 BCE

- Mezad Hashavyahu Ostracon, c. 630 BCE

- The Babylonian Chronicle (Chronicle 5)- Nebuchadnezzar Besieges Jerusalem, 597 BCE

- Babylonian Ration List- King Jehoiakhin in Exile, 592/1 BCE

- Lakhish Ostraca, c. 587 BCE

- Jerucal ben Shelemiah Seal, 586 BCE

- Gemaryahu Son of Shaphan Bulla, 586 BCE

From David to Isaiah, c. 1000-700 BCE

Except for perhaps Moses, there is no greater hero in the Bible than David. He is introduced as the lad who single handedly defeated the mighty Philistine giant Goliath (1 Samuel 17). After a bitter conflict between the supporters of King Saul and of David finally ended, the elders of Israel came to David at Hebron and anointed him king over the entire people (2 Samuel 5-3). David’s long rule—more than 40 years—is seen by the Bible as a golden age.

The crowning of David as king was a threat to the Philistines. They attacked David’s forces twice but were repulsed both times. After that, the Philistines were no longer a major military problem for David.

David next turned to capturing Jerusalem. The city, despite two centuries of Israelite settlement all around it, had remained a Canaanite stronghold. David, however, was able to conquer it when his general Joab climbed the city’s tsinnor, perhaps a watershaft that led into the city, and surprised Jerusalem’s inhabitants. After having ruled from Hebron for seven years, David moved his capital to Jerusalem.

Jerusalem emerged as not only David’s political capital, however; he turned the city into Israel’s religious capital as well. He brought the Ark of the Covenant—which had accompanied the Israelites during their desert wanderings and which had accompanied them into battle–to Jerusalem. David also made plans to build a temple in the city atop the threshing floor he purchased from Araunah the Jebusite (2 Samuel 24-18), but the actual construction of that building would be accomplished by his son and successor.

David had a personal guard that formed the core of his army. In keeping with his initial victory against Goliath, the Bible portrays David as a great military leader. Once the Philistines were no longer a menace, David expanded his state to the east. He defeated the three nations on the other side of the Jordan River—the Moabites, the Edomites and the Ammonites. As a result, David ruled an area from the Red Sea to the Euphrates River. His power over the further reaches of his empire, however, was likely minimal.

The nature of David’s rule is the subject of ongoing debate among historians today. Some see the Biblical description of him and his empire as reasonably reliable (those academics are sometimes called Biblical maximalists). Others, however, see him as a minor local chieftan, if they even accept that he lived (they are called Biblical minimalists). The minimalists had been bolstered until recent years by the fact that there had been no reference to David outside the Bible and by the lack of finds from tenth-century B.C.E. Jerusalem. That is no longer the case, however.

In the early 1990s, excavators discovered a ninth-century inscription that mentions the “House of David,” no doubt a reference to the David’s dynasty. Recent excavations in Jerusalem have also changed our understanding of the city in David’s time. A massive stone retaining wall, called the Stepped-Stone Structure, was repaired during David’s time and certainly supported a very significant building above it. In 2005, archaeologist Eilat Mazar discovered a very large building just upslope from the Stepped-Stone Structure and which dates to the tenth-century B.C.E. She suggests the building was David’s palace.

The question of who would succeed David became a bloody one. His oldest son, Amnon, was killed by Absalom, David’s third son; Absalom, in turn, was killed by Joab, David’s general, for leading a revolt against the king (2 Samuel 15-19). That left David’s fourth son, Adonijah, as the heir apparent. But David promised his wife Bathsheba, with whom he had had his famous affair years earlier, that her son Solomon would inherit the throne. David’s retinue united around David’s choice.

After David’s death, Solomon moved quickly to solidify his rule. At the first sign of revolt by Adonijah, Solomon had his rival and his supporters killed or exiled. As a result, soon after ascending to the throne, “The kingdom was established in the hand of Solomon” (1 Kings 2-46).

Solomon enjoyed an unprecedented period of peace. His only possible threat, Egypt, attacked and captured the city of Gezer. But Egypt was relatively weak at this time, and the pharaoh moved to mend relations with Solomon. Pharaoh gave Solomon his daughter in marriage and gave him Gezer as a dowry (1 Kings 3-1).

Solomon developed close commercial ties with Hiram, the king of Tyre, in Phoenicia, north of Israel. Phoenicia supplied timber and building expertise in exchange for wheat and olive oil. Solomon cemented his relationships with neighboring kingdoms through the customary way of the time—by marriage with various princesses. Solomon also strengthened his domestic administration, expanding his cabinet (which included several scribes) and reorganizing his kingdom into 12 administrative districts. These districts included the newly acquired Canaanite city-states of Dor, Megiddo and Beth-Shean.

Solomon undertook major public projects, including the building of a wall around Jerusalem and the fortification of Gezer, Hazor and Megiddo with impressive six-chambered gateways (1 Kings 9-15). These projects required money and manpower. In addition, Solomon’s subjects were required to support his extensive harem and his expanding army, which was equipped with horses and chariots.

The most impressive of Solomon’s building projects were the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem, which took seven years, and the building of his palace, which required 20 years to complete. The raw materials for the buildings themselves and for their elaborate decorations came from abroad; Hiram’s architects provided the technical expertise that made the projects possible.

Such major projects came at a high cost, in both money and forced labor. Not surprisingly, Solomon’s subjects began to chafe on the burdens they had to bear to support his elaborate rule. Interestingly, their complaints against him took the form of objections to his many foreign wives and to the foreign gods whose worship Solomon supported in order to mollify those wives (1 Kings 11-4-7).

Thanks to the peace and prosperity during Solomon’s reign, ancient Israel moved from a tribal society with a herding and small village economy to a centralized state with major, fortified cities defended by a mobile army and with an economy fed by international trade. Luxury items began to appear, and even everyday pottery was of a higher quality than previously. The population also grew and may have doubled in the century from Saul’s reign to Solomon’s death. Literacy became widespread. We have known for years that there was some literacy in ancient Israel, thanks to the Gezer Calendar, a tenth-century B.C.E. listing of what is to be done throughout the agricultural year. To the Gezer Calendar we can now add a tenth-century B.C.E. abcedary—a listing of the alphabet—discovered at Tel Zayit, in the southwest of Judah. This growth in literacy may have led in the tenth century to the earliest compilation of Israelite history and religion, which would form one of the major strands of the Bible (and which scholars refer to as the J strand).

But Solomon’s successes came at a price beyond the grumblings of his subjects about his foreign wives and their tax burdens. Solomon’s centralization of Israelite worship at the Temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem, in the heartland of Judah, no doubt chafed the people of the northern lands of Israel. With the death of Solomon, those tensions soon erupted into outright schism. The relatively brief era of the United Monarchy forged by David and Solomon was over.

Solomon’s son Rehoboam ascended to the throne of Judah in about 930 B.C.E. He knew, however, that his rule would not be accepted without question in the north. 1 Kings 12 records that the new monarch went to Shechem in order to rally the support of the northern tribal leaders to his reign. The northern tribes expressed to the young monarch the concerns they had had with his father- the burdensome taxes and labor required to conduct Solomon’s building projects.

Rehoboam might have been able to gain the support of the northerners, but instead of seeking to placate them he reacted to their concerns with scorn. “My little finger is thicker than my father’s loins,” he taunted (1 Kings 12-10), meaning that they could expect even harsher treatment from the young ruler than they had from Solomon. Rehoboam had followed the advice of his young contemporaries, evidently rash and inexperienced newcomers to matters of state. It proved a terrible miscalculation. When Rehoboam sent his representative to raise a workforce in the north, the northern tribes stoned the man to death. They were now in open revolt. Their mutiny coalesced around Jeroboam the son of Nebat. Jeroboam had been placed by Solomon to oversee the workers from the tribes of Ephraim and Manesseh, but for reasons not explained by the Bible Rehoboam led a small revolt against Solomon. Rather than risk arrest, Rehoboam fled to Egypt and found refuge with Pharaoh Sheshonk (called Shishak in the Bible). When the northern tribes revolted against Rehoboam, they selected Jeroboam as their leader.

The turmoil in Judah and Israel gave a newly resurgent Egypt an opportunity to reassert itself in Canaan and to open unfettered access for itself on the Via Maris, the coastal trade route. The ambitious Shishak invaded Canaan in the fifth year of Rehoboam’s reign (about 925 B.C.E.). The attack is known from two sources—the Bible (in the Books of Kings and Chronicles) and from Shishak’s reliefs at the Great Temple of Amun in Thebes (modern Luxor). While the Biblical account makes it seem that Shishak’s primary target was Jerusalem and cities of Judah (which is an indication that the Biblical writer was from Judah), the pharaoh’s list of conquered sites makes it clear that he attacked cities in both the north and the south (more, in fact, in the north than in the south). Shishak was not, therefore, acting in support of Jeroboam, the man to whom he had formerly given sanctuary, but was acting in his own interests.

Shishak seems to have wreaked more destruction in the north than in the south. Rehoboam was able to have his cities spared thanks to a heavy tribute he paid to the pharaoh. 1 Kings 14-26 says that Rehoboam gave Shishak all the treasures from the Temple and the royal palace. The main cities in Judah were thus spared, but when Shishak returned to Judah after ravaging the north, he attacked a number of cities south of Judah, in the northern Negev.

Shishak laid the heaviest hand, though, on the cities of the newly formed northern kingdom of Israel. Archaeologists have noted two things about the cities Shishak attacked in the north; first, the tenth-century B.C.E. cities that were destroyed had been of high quality, giving support to Solomon’s reputation in the Bible as a great builder, and second, that those cities were quickly rebuilt. Shishak’s assault on Canaan did not have long-lasting consequences.

For the historian, Shishak’s invasion is extremely important. For the first time we have a good overlap between the Bible’s account of events, extrabiblical accounts (in this case, the Egyptian historical record) and the data uncovered by archaeologists, which confirms a wide pattern of destruction even at sites not found in Shishak’s list of conquered cities (which is no longer complete).

The Bible records that after Shishak’s invasion, Jereboam led the northern tribes from various locations, but it is far more concerned to note that he established cult centers at Dan and Bethel. For the Biblical writers, this act violated what they saw as a central principle- that worship of Yahweh take place only at the Temple in Jerusalem. Jereboam, for his part, may have feared that if the people of the northern tribes made annual pilgrimages to Jerusalem, their political allegiances might shift to his rival, Rehoboam.

The first years of the Divided Monarchy were bloody ones. Rehoboam died after 17 years on throne; we know little about the rule of his son, Abijam, other than that the Bible says he defeated Jeroboam in a major battle in the territory of Ephraim. In the north, Jeroboam enjoyed 22 years on the throne, but his successor, his son Nadab, was soon assassinated by one of his officers, Baasha son of Ahijah. Baasha brutally secured his rule by massacring the surviving members of Jeroboam’s family. Baasha’s rule, though long (about 23 years), was marked by frequent warfare between Israel and Judah.

These wars between the two kingdoms soon drew in players from the international arena. At one point, Baasha’s forces captured the fortress at Ramah, just north of Jerusalem, and imposed an embargo on Judah’s capital city. In response, the king of Judah, Asa, the grandson of Rehoboam, turned for help to Ben-Hadad, king of Aram-Damascus. Asa, in an echo of his grandfather’s payment to Pharaoh Shishak, offered much gold and silver from his palace treasury and from the Temple as inducement to Ben-Hadad to invade Israel. The bribe worked; Ben-Hadad attacked and Baasha was forced to lift the embargo against Jerusalem and retreat to his own territory.

Baasha had a bloody but just end. He was assassinated in his palace by an officer named Zimri, who then massacred Baasha’s surviving family (as Baasha had massacred Jeroboam’s family). Zimri’s rule did not last long, however; the army rallied around Omri, the head of the Israelite army, Zimri killed himself, and after a brief challenge Omri ascended to the throne.

Omri, though he is not the subject of much Biblical interest (the Biblical writers were much more concerned with his son Ahab), was a ruler of many accomplishments. Halfway through his 12-year reign, Omri moved the capital of the northern kingdom from Tirzah, from where Jeroboam ruled, to the new site of Samaria, near Shechem. The new capital was located along roads that led to, and therefore fostered trade with, Phoenicia. In fact, Omri’s rule, as well as the reign of his son, was marked by close economic and cultural ties between the Israelite kingdom and Tyre, the Phoenician capital. But under Omri’s rule, Israel gained the attention of kingdoms in addition to Phoenicia. Neo-Assyrian records refer to the lands of Bit Humri, the House (or Dynasty) of Omri.

Ties between Israel and Tyre were cemented by the marriage of Omri’s son Ahab to Jezebel, the daughter of King Ittobaal of Tyre. Few persons in the Bible are portrayed with as much contempt as Ahab and Jezebel (they are seen as massively dishonest and champions of a foreign deity), but the good relations between the two kingdoms benefited both nations- Israel stood at the juncture between east-west caravan routes from the Mediterranean and the King’s Highway, and the north-south route from the Gulf of Aqabah to Damascus.

Israel prospered under Omri. In addition to Phoenician pottery and Phoenician-style building materials, archaeologists excavating in northern Israel have uncovered many examples of carved ivory—a hallmark of Phoenician luxury. These recall “the ivory house” built by Ahab in Samaria (1 Kings 22-39) and “beds of ivory” mentioned by the prophet Amos in his oracles against the northern kingdom (Amos 6-4).

The prosperity enjoyed by the Israelite kingdom continued under Ahab, Omri’s son, who ruled from 872 to 851 B.C.E. During the reigns of both Omri and Ahab, Israel undertook major building projects. In Samaria, Ahab built an elaborate palace, and huge public structures have been uncovered in other important northern cities, particularly at Dan, Hazor, Jezreel and Megiddo.

To the Biblical writers, though, Ahab and his queen, Jezebel, are the epitome of evil rulers. They are depicted as cheating their subjects and as promoting the worship of the Phoenician God Baal in Israel. Their main adversary, in the pages of the Bible, is the great prophet Elijah.

Despite the scorn with which Bible treats Ahab and Jezebel, they maintained a largely peaceful and prosperous kingdom, even making peace with Jehoshaphat, who had succeeded his father Asa to the throne of Judah.

But the fate of the Israelite kingdom would more and more be determined by events to its north, especially by the growing power of Assyria. This kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, based at capitals at Calah and Nineveh, was the dominant power in the region during the ninth to seventh centuries B.C.E.

Assyria first made its mark under the leadership of Assurnasirpal II (884-859 B.C.E.), a brutal general who waged campaigns against the Aramean states, west into Syria and even as far west as the Mediterranean coast. Successful as he was, however, Assurnasirpal did not have much effect on Israel, much less the southern kingdom of Judah.

Shalmaneser III (859-824 B.C.E.), Assurnasirpal’s son and successor, had a much greater impact on the southern Levant than did his father. Shalmaneser instituted a policy of annual campaigns against neighboring lands, and soon many of the states in northern Syria were paying tribute to him. Other states formed alliance against him; the leaders of the coalition were Hadadezer of Damascus and Ahab of Israel. The two sides began confronting each other in 853 B.C.E According to the Assyrian annals, Hadadezer provided 1,200 chariots and horsemen and 20,000 soldiers to the effort, while Ahab contributed 2,000 chariots and 10,000 soldiers. These battles raged annually, with Shalmaneser unable to subdue the coalition. When Hadadezer died in 845 B.C.E., his throne was usurped by Hazael. This event is the subject of 2 Kings 8-7-15, in which the prophet Elisha foretells the devastation Israel would suffer at the hands of Hazael.

Despite Shalmaneser’s repeated attacks on Hazael, particularly in the campaigns of 841 and 838 B.C.E., the Assyrians were unable to defeat their Syrian foe. Indeed, after 838, Hazael was able to expand his empire, particularly in southern Syria and then in Israel. Hazael’s ambitions in the south would soon bring him into direct bloody conflict with both the kingdom of Israel and the kingdom of Judah.

By this time, Ahab had passed from the scene, having died sometime after 853 B.C.E. He was briefly succeeded by his oldest son, Ahaziah, but the latter’s reign was short-lived; 2 Kings 1-2-17 records that he tumbled to his death from the balcony of his palace. Joram, a younger son of Ahab, assumed the throne in 850 B.C.E. and ruled until 841 B.C.E. Assyrian records from this time mention that the empire was still opposed by a 12-king coalition led by Damascus, and we assume Joram was one of those dozen rulers.

Joram rule in the north overlapped with the reign in Judah of Jehoram, son of Jehoshaphat (Joram and Jehoram are variants of the same name; both mean “Yahweh is exalted”). Jehoram ruled from 846 to 841 B.C.E. As we have noted, Jehoshaphat had made peace between Judah and Israel. To cement good relations between the two kingdoms even further, Jehoshaphat had arranged to marry Jehoram to Athaliah, the daughter of Ahab and Jezebel. Judah thus remained aligned with Israel during Jehoram’s rule. The alliance continued after Jehoram died in 841 B.C.E. and the succession to the throne by his son Ahaziah.

With Joram and Ahaziah in place as the kings of Israel and Judah, the stage was set for an international confrontation that would be followed by a bloody internal coup. Events began when Joram and Ahaziah attacked Hazael of Damascus at Ramoth-gilead, in Trans-Jordan (the battle is mentioned in 2 Kings 8-28). The attack was likely prompted by Hazael’s pressure against Israel in the preceding years, but it may have had a specifically economic cast- Ramoth-gilead sat alongside important trade routes. Hazael seems to have had the better of the fight, because Joram was wounded in the battle and had to retreat to Jezreel, where he was soon joined by his ally Ahaziah. The forces of Israel and Judah were left in the charge of an officer named Jehu. With Joram no longer present to lead his forces in battle, the Israelite soldiers proclaimed Jehu king. Jehu wasted no time in establishing himself as the unquestioned monarch. He went immediately to Jezreel, where he killed Joram and then hunted down Ahaziah after he had fled the city. In the time-honored fashion of such bloody coups, Jehu had the descendants of both toppled kings captured and then killed. Even Jezebel, Ahab’s widow and Israel’s queen mother, suffered an ignoble death- She was thrown from a window at her palace in Jezreel and her body was left in the street to be eaten by dogs. To the Biblical writers, Jezebel’s gruesome end had been foretold earlier in 1 Kings 21-23 by the prophet Elijah. Another Biblical prophet, Hosea referred to the violent coup and its aftermath as “the blood of Jezreel” (Hosea 1-4). The Bible sees Jehu’s actions as more than merely political or military—it describes them in religious terms. For the Bible, Jehu “wiped out Baal from Israel” (2 Kings 10-28).

Some scholars have suggested that Jehu, by destroying two members of the anti-Assyrian league, acted to win the favor of Assyria. Recently discovered evidence, however, suggest that Jehu was not acting for the benefit of Assyria but for Hazael of Damascus instead. The evidence comes from three surviving fragments of an inscription carved into a black basalt monument. Called the Tel Dan inscription, after the northern Israelite city where it was discovered in 1993 and 1994, the fragments suggest it was written by a victorious king of Aram-Damascus to commemorate a victory over Israel (this inscription is the same one mentioned earlier as bearing the phrase “House of David”). Two kings are said to have been killed; though their names are incomplete on the inscription, the only possible reconstruction seems to be Joram and Ahaziah. The only king of Damascus who was a contemporary of both kings is Hazael. He seems to be claiming credit not only for the defeat of both kings in battle, but also for deaths. What the Bible describes as an internal coup, the Tel Dan inscription sees as an act orchestrated by Hazael.

The Tel Dan inscription refers to Ahaziah as the king of the House of David, the first appearance outside the Bible of the name David, and confirms that the ruling house of Judah consisted of descendants of King David. Indeed, the Bible uses the term “House of David” 21 times to refer to the rulers of Judah.

If Jehu thought his coup against the kings of both Israel and Judah would result in a resurgent Israelite kingdom, he was wrong. 2 Kings 10-32-33 asserts that after the bloody events at Jezreel, “the Lord began to trim off parts of Israel.” The trimming began with the loss to Hazael of Israelite lands east of the Jordan. Scholars are unsure whether the loss of these lands was a friendly concession by Jehu to Hazael in gratitude for the latter’s political and military support, or a conquest by Hazael in response to what he perceived as an act of treachery against him by Jehu. In 841 B.C.E. Shalmaneser campaigned again against Damascus but was unable to capture the pesky Hazael. Instead, he marched to the Mediterranean coast where, in exchange for sparing their lands, Shalmaneser accepted tribute from several smaller kingdoms. Among those offering tribute to the mighty Assyrian ruler was Jehu of Israel; the act is commemorated on the famous Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser, a 7-foot-tall black slab that shows on one of its registers the Assyrian king admiring a vessel that has been given to him as tribute while a figure kneels in front of him and kisses his feet, An inscription on the obelisk identifies the person performing obeisance as “Yaw, son of Omri.” Yaw is presumably Jehu, and he is identified as the son of Omri because he had assumed the throne of Israel, the Omride kingdom.

Jehu’s tribute to Shalmaneser no doubt angered Hazael, Assyria’s longtime foe. As it happened, for the remainder of the ninth century B.C.E. Assyria would cease to be a factor in the lands to its west and south. It was Hazael of Damascus who would assume the role of conqueror.

Jehu’s assassination of Ahaziah of Judah threw the southern kingdom into turmoil. Ahaziah’s mother Athaliah (the daughter of Ahab and Jezebel) assumed the throne. Needless to say, her first act as queen was to attempt to kill every surviving member of Judah’s royal family. She was foiled by Jehosheba, the sister of Ahaziah, who hid her infant nephew Jehoash, the son of Ahaziah, and put him in the care of the High Priest. After seven years of hiding in the Temple, the lad was proclaimed king and Athaliah was executed. The Biblical writers view Jehoash as a good ruler and credit him with ordering much-needed repairs to the Temple (in contrast, Athaliah seems to have maintained her family’s devotion to Baal; after her death, 2 Kings11-18 says “the house of Baal” in Jerusalem was destroyed).

Jehoash, like his counterpart to the north, had to deal with Hazael. In about 812 B.C.E. the king of Damascus marched south and conquered cities along the coast; he then turned east and threatened Jerusalem. Like many of his predecessors, Jehoash was able to save the city only by surrendering the gold in his palace and Temple treasuries to Hazael. For his part, Hazael now found himself in control of both the Via Maris, the trade route along the coast, and of the King’s Highway, the main route east of the Jordan.

Damascus enjoyed its prominent position in the region for about a quarter century, from roughly the 830s to 805 B.C.E. By the end of the ninth century, however, Assyria was once again on the rise, led by Adad-nirari III (811-783 B.C.E.). This development was bad for Damascus, which was a principal target of Assyrian might, but good for Israel, Judah and other smaller kingdoms that had been under the yoke of Damascus. 2 Kings 13 4-5 says that the Lord “saw the oppression of Israel, how the king of Aram [Damascus] oppressed them. Therefore the Lord gave Israel a savior, so that they escaped from the hand of the Arameans; and the people of Israel lived in their homes as formerly.” The passage seems to describe the political situation following Adad-nirari’s subjugation of Damascus. In the wake of those developments, the ruler of Israel at the time, Joash (802-787 B.C.E), defeated Damascus three times in battle and reconquered Israelite territory that had been lost to Hazael and his successors. Joash’s counterpart in Judah, Amaziah (801-783 B.C.E.), was similarly emboldened to attack Edom. Amaziah proved to be a rash leader; he goaded Joash of Israel, perhaps thinking that he could gain territory from Israel as well while Joash was pinned down by Damascus. In any event, Amaziah’s taunt proved to be badly misguided- Joash captured Amaziah while attacking Beth-Shemesh, west of Jerusalem, and then attacked the capital itself, destroying its defenses and looting the Temple and royal palace. Judah was now little more than a vassal of Israel.

The first half of the eighth century B.C.E. was a prosperous time for the kingdoms of both Israel and Judah. This was thanks to the relative weakness at the time of Damascus and Assyria. After humbling Damascus, Assyria was led by unimpressive rulers, who were forced to quell rebellions closer to home. Assyria would not again be a significant factor in either Israel or Judah until the middle of the century. Freed from these two major powers, Jereboam II, the son of Joash, restored the former glory of the Israelite kingdom under the Omrides, going so far as to expand his borders from the Orentes in Syria down to the Dead Sea (2 Kings 14-25).

The prosperity in Israel is confirmed by the prophet Amos, who excoriates the kingdom for its many religious and social failings but who also describes the wealth enjoyed by the ruling class. “Alas for those who lie on beds of ivory,” the prophet warned, “and lounge on their couches, and eat lambs from the flock, and calves from the stall; who sing idle songs to the sound of the harp, and like David improvise on instruments of music; who drink from bowls, and anoint themselves with the finest oils, but are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph!” (Amos 6- 4-6).

The kingdom’s increased wealth was marked especially by the widespread use of carved ivory inlays, a material and a style of decoration popular in Phoenicia. For the prophet Amos, ivory is the perfect symbol of the excesses of the rich in Israel (see also Amos 3-15).

The control of trade routes led not only to short-term prosperity but also to longer-term developments. Excavations of sites dating to the first half of the eighth century B.C.E. have revealed not the founding of new cities but the rebuilding on a larger and better-defended scale of old ones. Not surprisingly, the building boom was accompanied by a population boom.

This period also saw an increase in literacy. A seal from this time, uncovered at Megiddo but now lost, is inscribed “Shema the servant of Jeroboam”; it likely belonged to an important royal official posted to Megiddo. A very large cache of inscribed potsherds, called the Samaria ostraca, was found near the palace of the royal capital in 1904 and dates to the 770s B.C.E.

Scholars have noted that many of the names mentioned in the Samaria ostraca contain part of the divine name Yahweh, but more than half again as many contain the Phoenician divine name Baal. These may have belonged to Phoenicians who were living in the kingdom (some of them, no doubt, artisans who were responsible for the ivory carvings), but these names may also indicate that “Baal” had come to be accepted in Israel as a name for Yahweh (Hosea 2-16 says, “On that day, says the Lord, you will call me ‘My husband,’ and no longer will you call me ‘My Baal’”). In either case, the continued religious and cultural influence of Phoenicia on Israel is clear, which explains the antipathy felt by the Book of Kings against Jeroboam II. Indeed the Book accuses him of perpetuating “all the sins of Jeroboam of Nebat” (his namesake and the founder of the breakaway kingdom)—sins that Kings sees as eventually leading to the destruction of the kingdom.

The period was a prosperous one in Judah as well. Under Azariah (also called Uzziah), the kingdom fought successfully against the Philistines and tribes in Arabia and exerted its control in those areas by fortifying cities and military posts along trade routes. Judah was still a junior partner to Israel, so its expansion to the west and south also benefited the northern kingdom. 2 Chronicles 26-11-15 credits Azariah with greatly strengthening the army and with fortifying the towers of Jerusalem with machines that could hurl arrows and large stones against potential attackers. The very next passages, though (2 Chronicles 26-16-22), claim that the king usurped some of the prerogatives of the High Priest by bringing an offering to the Temple himself rather than having the priest do it. The king was punished with leprosy, which forced him to live apart from others. His son Jotham then ruled as co-regent. When Azariah died, his disease kept him from being buried in the main part of the royal cemetery; a plaque from the Herodian period suggests, however, that his body was later moved.

The peace and prosperity enjoyed by Israel and Judah in the first half of the eighth century B.C.E. led to the development of complex societies in both kingdoms. Each kingdom was a centralized monarchy, ruled from the capital cities of Samaria and Judah, respectively. Each kingdom also had significant other cities- Dan, Hazor and Megiddo in Israel and Beersheba and Lachish in Judah.

At the top of the social stratum were the king and his royal family, followed by a nobility that served as local rulers and administered regional centers. The great bulk of the population, however, lived off the land by farming or by maintaining flocks. In addition to growing grain, these agriculturalists also cultivated dates, pomegranates, grapes, figs and olives; in some areas, a surplus in grapes and olives led to a thriving export economy.

As two centuries before, society was organized around the bet ab, “the father’s house,” an extended family of perhaps three generations who inhabited a four-room house—the typical domestic structure of the time. These were two-story buildings with an open courtyard in the middle in which an extended family could live, prepare food, shelter animals and store supplies. A cluster of such houses allowed an even larger extended family to live near and support each other.

Matters of law were typically resolved within a village by local elders, though sometimes property disputes would require the intervention of royal officials; these more significant cases led at times to grumbling by the locals over what they saw as the high-handedness of the royal court, an unhappiness often captured by the prophets in their condemnations of a king’s abuses.

Public matters were the realm of male decision-making and action. Women were expected to bear and raise children and to manage daily household tasks. For legal and economic matters, women were dependent on their fathers or husbands; widowed and divorced women were therefore especially vulnerable, leading the Bible to call numerous times for their special care.

Eighth century B.C.E. society could thrive and reach this level of complexity thanks to an extended period of calm. That period of calm was in turn possible thanks to a dormant Assyrian empire. With the rise of Tiglath-pileser III to throne (745-727 B.C.E.), that dormancy came a swift end.

Tiglath-pileser would embark on three western campaigns, each of which would have an increasingly devastating impact on the kingdoms to the south, particularly Israel. The first, in 743 to 738 B.C.E., resulted in an expansion of Assyrian power to the west and south and led to the empire receiving tribute from Damascus and Israel. The ruler of Damascus at this time was a man named Rezin, while Israel was ruled by Menahem. Menahem had an especially bloody route to the kingship. After Jeroboam’s death, his son Zechariah became king; his rule, however, was cut short after about only six months by an assassin named Shalum son of Jabesh. Shalum had an even shorter reign—after only one month he was assassinated by Menahem, who went on to rule for more than a decade (747-738 B.C.E.),

Menahem’s long rule came at a price—paying tribute to Tiglath-pileser. 2 Kings 15-20 records, “Menahem exacted the money from Israel, that is, from all the wealthy, fifty shekels of silver from each one, to give to the king of Assyria.” In return, Tiglath-pileser withdrew from Israel and did not devastate the kingdom.

Menahem’s son Pekahiah succeeded to the throne but ruled only for two years. He was assassinated by Pekah, who led an anti-Assyrian group within the kingdom. It is likely that Pekah had the encouragement of Rezin of Damascus, the longtime seat of anti-Assyrian sentiment.

For much of this time, Judah was still ruled by Jotham, the coregent for his father, Azariah the leper. 2 Kings 15-32-38 and 2 Chronicles 27-3-4 credit Jotham with extensive construction and renovation work in Jerusalem and elsewhere in Judah. This work was likely not done out of concern for the still-distant Assyria; Judah was not one of the kingdoms that were forced to pay tribute but out of fears of an attack from the much closer Israel and Damascus.

Jotham was succeeded as king of Judah by Ahaz in 735 B.C.E. 2 Kings 16-5 asserts that Rezin of Damascus and Pekah of Israel besieged Jerusalem but were unable to capture it. Historians believe that they may have been trying to force Ahaz to join them in an anti-Assyrian alliance. If that was indeed their motivation, they badly misjudged the situation; rather than joining the two kings, Jotham turned to Tiglath-pileser for help—help that came at a price, of course; in the time-honored way of such things, Jotham presented Tiglath-pileser with the gold and silver from the Jerusalem temple and royal palace. In return, Tiglath-pileser, now embarked on his second western campaign (734-732 B.C.E.), in which he would capture Damascus and exile its people and kill Rezin.

Tiglath-pileser’s second campaign significantly changed the political map of the region. Even before he defeated Damascus, the Assyrian monarch conquered Phoenician cities along the Mediterranean coast, Philistine cities further south and went as far as “the Wadi of Egypt” (Wadi el-Arish), the southern border of Palestine. While Damascus was still under siege, in 733 B.C.E., Tiglath-pileser turned his attention to Israel. He captured the lands of Naphtali (between modern Haifa and Tyre), upper Galilee and northern Transjordan. Following Assyrian policy, more than 13,000 Israelites were deported. The Israelite kingdom survived only when Hoshea son of Elah assassinated Pekah and pledged his loyalty to Tiglath-pileser.

The portion of Israel that survived the ravages of Tiglath-pileser’s campaign was little more than a rump state that consisted of only the highlands of Ephraim. Tiglath-pileser was now in control of the Via Maris, the trade route along the Mediterranean coast, and he had indirect control—thanks to the tribute paid to him by the local kingdoms–of the King’s Highway, the inland route that carried goods from Arabia to Syria and beyond.

The peaceful period between Israel and Assyria did not last long, however. Tiglath-pileser died in 727 B.C.E. and was succeeded by Shalmaneser V. The historical record and the Biblical account are incomplete, but it seems that Hoshea may have become involved with a revolt against Tyre that brought Shalmaneser west. Either on his way to or from Tyre, Shalmeneser, in about 725 B.C.E., marched against Israel and laid siege to Samaria, a siege that lasted for three years. Though Shalmaneser eventually captured Samaria in 722 B.C.E., he died a few months later.

His successor, Sargon II (722-705 B.C.E.) boasted of having captured Samaria, but both the Bible and the Babylonian Chronicle make clear that it was Shalmaneser who was responsible for that. What Sargon was responsible for, however, was the deportation of the Israelites to Assyria in 720 B.C.E. (the brief Biblical account, in 2 Kings 18-9-11, makes it seem that Shalmeneser was responsible for both the capture of Samaria and the exile of the Israelite kingdom’s inhabitants in 722 B.C.E.). Sargon was responding to a revolt against him in Gaza, an uprising that was quickly joined by Damascus and Samaria.

Sargon quelled the revolt and extended his rule to the border of Egypt, which for the first time was forced to pay tribute to Assyria.

Sargon inflicted on the Israelites a practice made infamous by Tiglath-pileser- the two-way relocation of conquered peoples. Vanquished regions in the west saw their inhabitants forcibly removed to the eastern parts of the Assyrian empire, and peoples from the east were exiled west. 2 Kings 17-6 records that the Israelites were “carried away to Assyria,” while 2 Kings 17-24 notes that peoples from Babylon and elsewhere in the east were sent to Samaria.

The 200-year history of the northern kingdom of Israel, which for a time was a regional power, thus came to an end. Its lands were now the Assyrian provinces of Dor, Gilead, Megiddo and Samaria. Its people soon disappeared from history and thereafter became known as the fabled Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

From Isaiah to Jeremiah, c. 700-586 BCE

The story of Biblical history now shifts to the south, and very soon after the northern kingdom ceased to exist the southern kingdom came to be led by one of the key figures in ancient Israelite history. Hezekiah succeeded his father Ahaz to the throne when Ahaz died in 727 B.C.E. Hezekiah ruled for three decades, until 697 B.C.E., and he embarked on bold courses on two fronts- he introduced major reforms to religious practice that had a significant impact on Israelite religion and he took a defiant stand against Assyria, a stand from which he would quickly have to retreat. We are fortunate that we have ample records of Hezekiah’s actions, both from the Bible and from other sources. The Bible records the events of Hezekiah’s rule in the Book of Kings and in the Book of Chronicles, the Bible’s two accounts of Israel’s royal history, and in Isaiah 1-33, in which we get the prophet’s view of the events surrounding Hezekiah and the prophet’s own thoughts and advice to the king. We have further evidence in the form of inscriptions, ranging from a major inscription—the Siloam Inscription, which documents the work of the laborers who dug a water tunnel in preparation for an Assyrian attack—to humble jar handles stamped with the word lemelekh (“belonging to the king”), which may have contained supplies stored in preparation of the Assyrian attack. In addition, we are fortunate to have an extensive record of the Assyrian viewpoint, which was preserved not only in their annals but also in visual form on grand reliefs carved on the walls of the royal palace.

The Bible views Hezekiah, thanks to his religious reforms, in a very positive light. 2 Kings 18-1-8 credits Hezekiah with removing bamot (“the high places” or altars that served as local shrines), breaking down pillars that indicated that a particular place was to be treated as holy, cut down the asherah (which may have been a sacred tree or pole and which may have represented a consort to Yahweh, the Israelite God) and destroyed the Nehustan, the snake that Moses himself is said to have fashioned out of bronze. Except for the Nehushtan, all the cult objects destroyed by Hezekiah had long been condemned by the Bible, which explains why the Bible views Hezekiah so favorably. It should also be noted that the cult objects Hezekiah destroyed were not a part of Assyrian religion; Hezekiah’s religious reforms, therefore, should not be seen as part of his later revolt against Assyria. On the contrary, scholars believe that the religious reforms occurred early in Hezekiah’s reign, suggesting that they were a priority for him; his revolt against Assyria did not happen until late in his rule.

For two decades, Hezekiah seems to have been content to be a vassal to Assyria, but for reasons that are not clear, he began to chafe under the domination of that great power when Sennacherib succeeded his father Sargon II to the throne in 705 B.C.E. Hezekiah’s attempt to wriggle free of Assyria came at an odd moment- Assyrian rule was strong in the west, the area that included Judah, so much so that the era is called by historians the age of the Pax Assyriaca. Indeed, Hezekiah’s revolt was the only time that Sennacherib had to send his army west to quell an uprising.

Hezekiah was not alone in attempting to free his kingdom from the Assyrians. At the death of Sargon, Babylon rebelled in the east; in the west, Sidon, Ashkelon, and Ekron also rebelled. Egypt, no doubt hoping to regain territory it had previously lost to Assyria, supported the revolt.

Sennacherib responded by systematically attacking each of the rebellious states. He first quelled the revolt in Babylon and then turned his attention to the west. He subdued Sidon and then marched south along the coast; Ashkelon and then Ekron succumbed to his mighty army. Hezekiah was Sennacherib’s sole remaining adversary.

Sennacherib’s devastating foray into Judah is recorded in 2 Kings 18-13-19 to 19-37 and in the Assyrian records; the two corroborate each other to a great degree. Bible scholars have noted that the Biblical account contains two distinct sections; the first (2 Kings 18-13-16) summarizes the havoc caused by Sennacherib, leading Bible scholars to suggest that it is based on a source familiar with the events. The rest of the Biblical account emphasizes the role of the prophet Isaiah and his view that Hezekiah not surrender to Sennacherib. Because of this viewpoint, scholars have tended to dismiss the historical reliability of this section of the Bible’s account, but recent studies—noting Assyrian language and outlook contained in the account—have suggested that even this portion of the Biblical narrative is based on a direct knowledge of the events.

Sennacherib boasts in his annals of destroying 46 cities in Judah, including the fort-city of Lachish. In addition, the siege and capture of Lachish and the subsequent expulsion of the city’s inhabitants are depicted on wall reliefs in the royal palace at Nineveh. It seems that Lachish served as Sennacherib’s base of operations for his campaign against Judah; the Bible, early in its account, notes that Hezekiah sent a conciliatory note to Sennacherib at Lachish.

Both the Biblical and the Assyrian accounts make clear that Sennacherib besieged Jerusalem—Sennacherib boasts that he had trapped Hezekiah “like a bird in a cage”—but neither indicate for how long. In the end, Hezekiah was able to save Jerusalem, and his rule, by paying a stiff ransom. He withstood Sennacherib’s siege no doubt thanks in good part to the precautions he had taken before Assyria’s attack on Judah. 2 Chronicles credits Hezekiah with rebuilding Jerusalem’s city wall, adding a second wall around the city, and strengthening the millo (apparently a fortified area at the north end of the City of David, between the royal palace and the Temple).

Perhaps the most significant precaution Hezekiah took was to build a tunnel to shunt water from the Gihon Spring, Jerusalem’s perennial source of fresh water and which lay outside the city’s walls in the Kidron Valley, to a pool inside the city. Now known as Hezekiah’s Tunnel, the rock-cut channel snakes 1,750 in an S-shape beneath the city; it was built by two teams of tunnelers who began at opposite ends and worked their way to meet in the middle. How they accomplished this engineering feat is still a mystery.

The cutting of the tunnel was commemorated, perhaps by the chief of the project, in an inscription chiseled on the wall face about 20 feet from the southern end of the tunnel. It reads, “While the stonecutters were still yielding the axe, each man toward his fellow, and while there were still three cubits to be cut through, they heard the sound of each man calling to his fellow, for there was a fissure in the rock to the right and to the left. And on the day of the breaking through, the stonecutters struck each man towards his fellows, axe against axe, and the waters flowed from the source of the pool for 1,200 cubits.”

Hezekiah’s preparations allowed him to withstand the siege, but not to escape unscathed from Sennacherib. He was forced to pay a very high ransom—he had to empty his treasury and strip gold from the Temple entrance–and to declare himself a vassal of Assyria. For his part, Sennacherib must have felt that destroying Jerusalem was not worth his while; he had conquered the other kingdoms in the west, and Hezekiah was no longer a threat.

If Hezekiah was one of the Biblical authors’ favorite figures, his son Manasseh was one of their most reviled. He succeeded his father to the throne in 697 B.C.E. and ruled for the unusually long span of 55 years; he wielded power, however, over a very small kingdom that was under the heel of Assyria.

Manasseh appears in the Assyrian annals as one of several rulers who supplied material to the empire, but the Bible’s ire towards him is not due to his service to Assyria but to his religious practices. Where the Bible lauds Hezekiah and Manasseh’s grandson Josiah for their religious reforms, their bile towards Manasseh was caused specifically because he opposed such reforms. The harrowing passage in 2 Kings 20-11-14 even goes so far as to blame Manasseh for the calamity that awaited Judah, its destruction by the Babylonians- “Because King Manasseh has committed these abominations … I am bringing upon Jerusalem and Judah such evil that the ears of everyone who hears it will tingle … I will wipe Jerusalem as one wipes a dish, wiping it and turning it upside down. I will cast off the remnant of my heritage, and give them into the hand of their enemies; they shall become a prey and a spoil to all their enemies.”

It is important to note that, just as Hezekiah’s religious reforms were not a reaction against Assyrian religious practices, so too Manasseh’s counter-reforms were not an attempt to import Assyrian religion into Judah. Rather they were designed to return Israelite religious practice to the way they were in the days of King Ahaz, Manasseh’s grandfather, and before the reforms of Hezekiah. Specifically, Manasseh rebuilt the high places—the local shrines throughout the kingdom—that Hezekiah had destroyed ((2 Kings 21-3).

Manasseh’s actions were taking place in an era of great regional political turmoil. The Assyrian throne changed hands in 681 B.C.E. when Sennacherib was assassinated; following a power struggle, his youngest son Esarhaddon became king. Assyria then entered a period when it was wrestling with Egypt for dominance in its western lands, the area that included Judah. Manasseh, like other rulers under the domination of Assyria, provided troops to the empire to help fight Egypt.

Despite aid from its vassal states, the Assyrian empire was reaching its breaking point. Revolts in its eastern territories, particularly by the Babylonians in 652 B.C.E. would prove its undoing. During this period of upheaval, Manasseh may have entertained ideas of escaping from Assyrian domination. 2 Chronicles 31-14 records that Manasseh built an outer wall around the City of David and placed military officers in charge of cities throughout Judah. He may have made these efforts to prepare for an Assyrian attack in retaliation for withdrawing his vassalage to Assyria. It is ironic that Manasseh, whom the Bible portrays in so different a light than his father Hezekiah, nonetheless made the same effort—the building of another wall—that his father did, and for the same reason. Manasseh’s wall may have been identified by archaeologists.

The disintegration of the Assyrian empire provides the background for Judah’s own imminent demise. Manasseh’s long reign was followed by the very short reign of his son Amon (642-640 B.C.E.), who came to a bloody end in an assassination whose motivation remains murky. Amon was succeeded on the throne by his Josiah, who was only eight years old at the time. The first decade of Josiah’s rule is shrouded in mystery; Judah may have been rule by a regent (perhaps Josiah’s mother) or by a group of men who had engineered Amon’s murder. In any case, the Bible’s account of Josiah reign does not begin in detail until he is 18 (in 622 B.C.E.), and then it is primarily interested in his religious reforms.

The most central aspect of Josiah’s reforms, like those of Hezekiah’s before him, was the idea that the worship of the God of Israel could only take place in the Jerusalem Temple and be conducted solely by that temple’s priesthood. According to the account in 2 Kings 22, the cause of the reform was the discovery in the Temple by the High Priest Hilkiah of “the book of the law.” Scholars now believe that the book found was a copy of the Book of Deuteronomy; they believe that because of the strong similarities between Josiah’s reforms and the religious instructions contained in Deuteronomy. The most prominent of these are the condemnation of poles, pillars and high places that had been held to be sacred by many in Judah.

Josiah was as ambitious politically as he was religiously. He seems to have harbored a desire to extend his rule back into the former lands of the Northern Kingdom, and he may also have sought to expand his territory westward, to the former Philistine lands, as shown by an inscribed Hebrew potsherd from the time of Josiah’s reign that was discovered in Yavneh Yam, just south of Tel Aviv, in 1960.

By the time of Josiah’s reforms, Assyria was facing a two-pronged assault, from the Babylonians and the Medes. The two upstart powers captured Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, in 612 B.C.E., though Assyria managed to hold on as a greatly reduced power until 609 B.C.E.

It was against the backdrop of Assyria’s waning power that Josiah met his untimely end. For reasons still not clear to historians, Egypt seems to have decided to aid Assyria, perhaps hoping to share power in Syria and Palestine. For whatever reason, in 609 B.C.E. Pharaoh Necho II marched north with a large army. For equally unclear reasons, Josiah also decided to move north, and he crossed paths with Necho at Megiddo, located at a strategic pass in northern Israel; 2 Kings 23-29 records that “when Pharaoh Necho met him at Megiddo, he killed him.” It is not even certain whether there was a battle; it could be that discussions between the two kings turned suddenly ugly and that the powerful ruler of Egypt simply decided to do away with a nuisance.

For a brief time, Necho dominated Syria-Palestine; in Judah, he deposed Josiah’s son Jehoahaz in favor of another of another son, Jehoiakim. Egyptian rule was short-lived, however. In 605 B.C.E. Nebuchadnezzar took charge of the Babylonian army and twice defeated the Egyptians in key battles, first at Charchemish and then at Hamath. This left Babylon in control of the western lands and left it poised for further attacks against Egypt. It was a situation in which Judah would be caught in the middle, with devastating consequences for it.

Nebuchadnezzar would certainly have continued south with his conquests, but the death of his father in the summer of 605 B.C.E. required him to return home and accept the throne of Babylon; he would rule until 562 B.C.E. His conquests were delayed only shortly, however. In 604 he returned to the western lands and devastated the Philistine coastal city of Ashkelon. Officials in Jerusalem were concerned enough to declare a public fast (Jeremiah 36-9) and Jehoiakim soon agreed to become a vassal of Babylon, an arrangement that would last for three years.

In early 600 B.C.E. Nebuchadnezzar suffered one his few military defeats at Migdol, in the Nile Delta, and returned to Babylon. Pharaoh Necho seized the opportunity to mount a campaign of his own and captured Gaza. Jehoiakim decided to cast his lot with Egypt and ceased paying tribute to Babylon. It would prove to be a very costly mistake.

In the winter of 598/597 B.C.E. Nebuchadnezzar laid siege to Jerusalem; as it happened, Jehoiakim had died shortly before the siege and was succeeded by his son Jehoiachin. Jerusalem did not hold out long, surrendering in Adar (March) of 597. Nebuchadnezzar was relatively kind to Judah. He spared Jerusalem and only took Jehoiachin and members of Judah’s ruling class (about 8 to 10 thousand of them) into exile in Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar placed Mattaniah, a son of Josiah and the uncle of Jehoiachin, on the throne of Judah (and changed his name to Zedekiah).

Things were not to remain calm for long, however. Necho’s successors in Egypt asserted themselves in Syria-Palestine, a revolt took place in Babylon in 594 B.C.E. and Zedekiah attempted to rally several nations against the great power. Nebuchadnezzar put a quick end to that by marching into Palestine. In about 590, however, Egypt again tried to assert itself in the region, and Zedekiah rebelled against his Babylonian overlords. Once again, in early 587 B.C.E., Nebuchadnezzar marched on Jerusalem and began an 18-month-long siege of the city. Babylon’s military maneuvers are known to us in part from inscribed potsherds recovered at Lachich that record the increasing desperation in Judah at the expected onslaught.

The Babylonians broke through the city’s walls in July 586 B.C.E. Zedekiah tried to escape at night but was captured; Nebuchadnezzar ordered a particularly gruesome end for him- Zedekiah’s sons were killed in his presence, and he was then blinded and sent into exile. Jerusalem’s Temple was put to the torch the following month and a limited number of people were sent into exile.

Nebuchadnezzar moved the regional capital from Jerusalem to nearby Mizpah and named Gedaliah as governor. Gedaliah did not last long; he was assassinated by a champion of the Davidic royal line named Ishmael. The remnants of the local leadership, expecting a vicious Babylonian response, fled to Egypt; they took with them the prophet Jeremiah, who had in earlier days been jailed for his diatribes against those who opposed Babylon.

Steven Feldman, COJS

Overview

- The City of David is the Archaeological Portal to the History of the Jewish People, George S. Blumenthal, COJS.

- The City of David 1000-961, Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem- Sacred City of Mankind, Steimatzky Ltd., Jerusalem, 1991.

- Solomon’s Jerusalem 961-922, Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem- Sacred City of Mankind, Steimatzky Ltd., Jerusalem, 1991.

- Quotations from the Book of Isaiah

- Isaiah and Hezekiah 715-687, Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem- Sacred City of Mankind, Steimatzky Ltd., Jerusalem, 1991.

- The Fall…587, Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem- Sacred City of Mankind, Steimatzky Ltd., Jerusalem, 1991.

- Biblical History- From David to Isaiah, c. 1000-700 BCE, Steven Feldman, COJS.

- Biblical History- From Isaiah to Jeremiah, c. 700-586 BCE, Steven Feldman, COJS.

- The Divided Kingdom 922-722, Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem- Sacred City of Mankind, Steimatzky Ltd., Jerusalem, 1991.

- The Destruction of King Solomon’s Temple, George S. Blumenthal, COJS.

Artifacts

-

-

- Sarcophagus of Ahirom, 10th century BCE

- Mesudat Nahal Aqrav, 10th century BCE

- Earliest Aramaic Inscription, 10th century BCE

- Tel Zayit Inscription, 10th century BCE

- Public Building in the City of David, 10th century BCE

- Elah Fortress Ostracon, 10th century BCE

- Ain Dara Temple, 10th century BCE

- Bamah at Tel Dan, 10th century BCE

- Cult Room/Marzeah – Lachish Room 49, 10th century BCE

- Beehive, 10th-early 9th century BCE

- Large Horned Altar, 10th-8th century BCE

- Small Horned Altars

- King David, 1005-965 BCE

- Horned Altar from Megiddo, 1000-900 BCE

- Asherah, 10th-7th century BCE

- Cult Basin, 10th-7th century BCE

- Arad Temple, 10th-6th century BCE

- First Temple Bulla, 10th-6th century BCE

- Proto-Ionic Capital, c. 961–921 BCE

- Goliath Pottery, 950 BCE

- First Temple and Ark of the Covenant, 950 BCE

- Gameboard, late 10th century BCE

- Eshtemoa Silver Hoard, 10th-9th century BCE

- Relief and Stelae of Pharaoh Shoshenq I- Rehoboam’s Tribute, c. 925 BCE

- Shoshenq Megiddo Fragment

- Bronze Soldier from Megiddo

- Arad Archive, 900 BCE-early 6th century BCE

- Aramaic Inscription Bowl, 9th century BCE

- Ahab Signet Ring, 9th century BCE

- Seal of Jezebel, 9th–8th century BCE

- Samaria Ivories, 9th-8th century BCE

- Incense Shovels from Tel Dan, 9th-8th century BCE

- Bracelet of Shoshenq II, c. 890 BCE

- Winged Lion, c. 883-859 BCE

- King Ahab, 874–853 BCE

- The Triad of Osiris, c. 850 BCE

- Kurkh Stele, 853 BCE

- Annals Edition 1, 841 BCE

- Moabite Stone, c. 840 BCE

- Tel Dan Stele, c. 840 BCE

- Annals Edition 2- Marble Slab Inscription, 839 BCE

- Annals Edition 3 – The Kurba’il Statue, 839 BCE

- Annals Edition 4 – The Black Obelisk, 828 or 827 BCE

- Yahalu Lot, 833-821 BCE

- The Nora Stone, c. 831-785 BCE

- Arad-Nirari III Stone Slab, 810-783 BCE

- Arad-Nirari III Saba’a Stela, 810-783 BCE

- Bronze Bucket, c. 800 BCE

- Samaria Ostraca, 8th century BCE

- Stone Bowl Inscription, 8th century BCE

- Akiba Inscription, 8th century BCE

- Judean Pillar Figurines, 8th century BCE

- Kuntillet ‘Ajrud Fortress with Inscriptions, 8th century BCE

- Warren’s Shaft, 8th century BCE

- Homer, 8th century BCE

- Griffon, 8th century BCE

- Hebrew Ostracon, 8th century BCE

- Isaiah the Prophet, 8th century BCE

- Seal of Rephaihu ben Shalem, 8th century BCE

- Garden Tomb, 8th-7th century BCE

- Seal of Ishtar, 8th-7th century BCE

- Inscribed Hebrew Seals, 8th-6th century BCE

- Building Remains, 8th-6th century BCE

- Netanyahu ben Yaush Seal, 8th-6th century BCE

- Tel Al Rimah Stele, 797 BCE

- Seal of Shema, c. 788 BCE

- Chronicle on the Reigns from Nabonassar to Shamash-shum-ukin, 747-668 BCE

- The Pazarcik Stela, 773 BCE

- Founding of Rome, 753 BCE

- Deir-Alla Inscription, 750–700 BCE

- Azriyau Annal Fragment, 738 BCE

- Iran Stele, 737 BCE

- Cultic Bull Stelae, c. 732 BCE

- Tiglath-Pileser III in Chariot, 730 BCE

- Kalah Palace Annals of Tiglath-Pileser, 730 BCE

- Tiglath-Pileser III and the Syro-Ephraimite War- Kalah Palace Summary Inscription 4, 730 BCE

- Tiglath-Pileser III and the Syro-Ephraimite War- Kalah Palace Summary Inscription, 729 BCE

- The Babylonian Chronicle, 722 BCE

- The Annals of Sargon II, c. 722 BCE

- The Nimrud Prism, 720 BCE

- The Azekah Inscription, 720-701 BCE

- Assyrian Tribute List

- Assyrian Palace, c. 712 BCE

- Nineveh Annal Prism, 711 BCE

- Sennacherib, 705–681 BCE

- Sennacherib’s Quarry, 705–681 BCE

- Hezekiah’s Tunnel, 701 BCE

- Hezekiah’s (or Siloam) Tunnel Inscription, 701 BCE

- Bronze Crest, 701 BCE

- Hezekiah’s Defeat- The Annals of Sennacherib on the Taylor, Jerusalem, and Oriental Institute Prisms, 700 BCE

- Lakhish Reliefs at Nineveh, c. 700 BCE

- Physician’s Ointment Jar, c. 700 BCE

- Royal Steward Inscription, c. 700 BCE

- LMLK Seal, c. 700 BCE

- The Annals of Sennacherib on the Nineveh Bulls, 694 BCE

- Silver Scroll Amulets from Ketef Hinnom, c. 600 BCE

- “House of God” Ostracon, early 7th century BCE

- Ekron Inscription, early 7th century BCE

- Edomite Seal, 7th century BCE

- Iron Sword, 7th century BCE

- Tel Miqne-Ekron, 7th century BCE

- Treatment for Ear-Ache, 7th century BCE

- Treatment for Headache, 7th century BCE

- The Prophet Jeremiah, 7th century BCE

- Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, 7th century BCE

- Archer Seal, 7th century BCE

- Wine Decanter, 7th-6th century BCE

- Edomite Shrine, 7th-6th century BCE

- Edomite Seal, 7th-6th century BCE

- Edomite Horned Figure, 7th-6th century BCE

- Beqa‘ Weight, 7th-6th century BCE

- Shlomit Seal, 7th-6th century BCE

- Seal Rings and Bullae from the End of the First Temple Period

- Vassal Treaties of Esarhaddon, 681-669 BCE

- Stele of Esarhadddon, 671 BCE

- Tablet Fragment from Nineveh, 671 BCE

- Ashurbanipal’s Conquest of Thebes, 663 BCE

- Mezad Hashavyahu Ostracon, c. 630 BCE

- The First Extra-Biblical Reference to the Sabbath, c. 630 BCE

- Golden Cobra, c. 603 BCE

- Arad Inscription, 609 BCE

- Arad Ostraca, c. 600 BCE

- Arrow and Arrowhead, c. 600 BCE

- Baruch ben Neriah Bulla, 6th century BCE

- The Babylonian Chronicle (Chronicle 5)- Nebuchadnezzar Besieges Jerusalem, 597 BCE

- Nebo-Sarsekim Cuneiform Tablet, 595 BCE

- Babylonian Ration List- King Jehoiakhin in Exile, 592/1 BCE

- Lakhish Ostraca, c. 587 BCE

- House of Ahiel, 586 BCE

- Jerucal ben Shelemiah Seal, 586 BCE

- Gemaryahu Son of Shaphan Bulla, 586 BCE

- Seal of Gedaliah, 586 BCE

- Arrowheads from Babylonian Destruction, 586 BCE

- Biblical Megiddo

- Juglet from Tell Beit Mirsim

- Ivory Pomegranate

-

Articles

- Introduction, Nahum Sarna, Songs of the Heart, Schocken Books, NY, 1993.

- A Kingdom Arises, Rina Abrams, COJS.

- Assyrian Ascension, Rina Abrams, COJS.

- The Fall of the Kingdom of Israel, Rina Abrams, COJS.

- The Assyrian Attack on Judea, Rina Abrams, COJS.

- By the Rivers of Babylon, Rina Abrams, COJS.

- Gila Hurvitz, The City of David, Institute of Archaeology Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1999.

- Iraq and the Bible, Bryant G. Wood.

- The Ancient Empires of the Middle East, Hadassah Levy, COJS.

- Elijah, Emil G. Hirsch, Eduard Konig, Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Ancient City of David To Be Re-Excavated, Mendel Kaplan, Biblical Archaeology Review (4:1), Mar 1978.

- The World’s First Museum and the World’s First Archaeologists, Lionel Casson, Biblical Archaeology Review (5:1), Jan/Feb 1979.

- The Evolution of Two Hebrew Scripts, Jonathan P. Siegel, Biblical Archaeology Review (5:3), May/Jun 1979.

- Was There a Seven-Branched Lampstand in Solomon’s Temple? Carol L. Meyers, Biblical Archaeology Review (5:5), Sep/Oct 1979.

- How Water Tunnels Worked, Dan P. Cole, Biblical Archaeology Review (6:2), Mar/Apr 1980.

- The Regional Study—A New Approach to Archaeological Investigation, Amnon Ben-Tor, Biblical Archaeology Review (6:2), Mar/Apr 1980.

- Jerusalem’s Water Supply During Siege, Yigal Shiloh, Biblical Archaeology Review (7:4), Jul/Aug 1981.

- The Remarkable Discoveries at Tel Dan, John C. H. Laughlin, Biblical Archaeology Review (7:5), Sep/Oct 1981.

- Ancient Musical Instruments: Introduction, Biblical Archaeology Review (8:1), Jan/Feb 1982.

- Ancient Musical Instruments: The Finds That Could Not Be, Bathja Bayer, Biblical Archaeology Review (8:1), Jan/Feb 1982.

- Ancient Musical Instruments: What Did David’s Lyre Look Like? Biblical Archaeology Review (8:1), Jan/Feb 1982.

- Ancient Musical Instruments: How Scholarly Communication Works, Biblical Archaeology Review (8:1), Jan/Feb 1982.

- Ancient Musical Instruments: “Sounding Brass” and Hellenistic Technology, William Harris, Biblical Archaeology Review (8:1), Jan/Feb 1982.

- In Search of Solomon’s Lost Treasures, Neil Asher Silberman, Biblical Archaeology Society (6:4), Jul/Aug 1980.

- New York Times Misrepresents Major Jerusalem Discovery, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (7:4), Jul/Aug 1981.

- BAR Interviews Yigael Yadin, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (9:1), Jan/Feb 1983.

- “And David Sent Spoils … to the Elders in Aroer” (1 Samuel 30-26–28), Avraham Biran, Biblical Archaeology Review (9:2), Mar/Apr 1983.

- Scholars’ Corner: Network of Iron Age Fortresses Served as Military Signal Posts, Biblical Archaeology Review (9:2), Mar/Apr 1983.

- News from the Field: The Divine Name Found in Jerusalem, Gabriel Barkay, Biblical Archaeology Review (9:2), Mar/Apr 1983.

- BAR Jr.: Five Ways to Defend an Ancient City, Oded Borowski, Biblical Archaeology Review (9:2), Mar/Apr 1983.

- Of Hems and Tassels, Jacob Milgrom, Biblical Archaeology Review (9:3), May/Jun 1983.

- Scholars’ Corner: Is the Solomonic City Gate at Megiddo Really Solomonic? Valerie M. Fargo, Biblical Archaeology Review (9:5), Sep/Oct 1983.

- Destruction of Judean Fortress Portrayed in Dramatic Eighth-Century B.C. Pictures, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:2), Mar/Apr 1984.

- News from the Field: Defensive Judean Counter-Ramp Found at Lachish in 1983 Season, David Ussishkin, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:2), Mar/Apr 1984.

- Scholars’ Corner: Yadin Presents New Interpretation of the Famous Lachish Letters, Oded Borowski, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:2), Mar/Apr 1984.

- The Mystery of the Unexplained Chain, Yigael Yadin, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:4), Jul/Aug 1984.

- Yigael Yadin 1917–1984, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:5), Sep/Oct 1984.

- Queries and Comments: Who Chiseled Out the Siloam Inscription? Biblical Archaeology Review (10:5), Sep/Oct 1984.

- Is the Cultic Installation at Dan Really an Olive Press? Suzanne F. Singer, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:6), Nov/Dec 1984.

- Who or What Was Yahweh’s Asherah? André Lemaire, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:6), Nov/Dec 1984.

- The Fortresses King Solomon Built to Protect His Southern Border, Rudolph Cohen, Biblical Archaeology Review (11:3), May/Jun 1985..

- Ancient Ivory, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (11:5), Sep/Oct 1985.

- Ancient Seafarers Bequeath Unintended Legacy, Osnat Misch-Brandl, Biblical Archaeology Review (11:6), Nov/Dec 1985.

- The City of David After Five Years of Digging, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (11:6), Nov/Dec 1985.

- Jerusalem Tombs from the Days of the First Temple, Gabriel Barkay and Amos Kloner, Biblical Archaeology Review (12:2), Mar/Apr 1986.

- Why the Moabite Stone Was Blown to Pieces, Siegfried H. Horn, Biblical Archaeology Review (12:3), May/Jun 1986.

- From Ebla to Damascus: The Archaeology of Ancient Syria, Marie-Henriette Gates, Biblical Archaeology Review (12:3), May/Jun 1986.

- Solomon’s Negev Defense Line Contained Three Fewer Fortresses, Rudolph Cohen, Biblical Archaeology Review (12:4), Jul/Aug 1986.

- The Iron Age Sites in the Negev Highlands, Israel Finkelstein, Biblical Archaeology Review(12:4), Jul/Aug 1986.

- BAR Interviews Avraham Eitan, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaelogy Review (12:4), Jul/Aug 1986.

- The Search for Roots, Helen Frenkley, Biblical Archaeology Review (12:5), Sep/Oct 1986.

- Why King Mesha of Moab Sacrificed His Oldest Son, Baruch Margalit, Biblical Archaeology Review (12:6), Nov/Dec 1986.

- Lachish—Key to the Israelite Conquest of Canaan? David Ussishkin, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:1), Jan/Feb 1987.

- Arad, Ze’ev Herzog, Miriam Aharoni, and Anson F. Rainey, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:2), Mar/Apr 1987.

- The Well at Arad, Ruth Amiran, Rolf Goethert, and Ornit Ilan, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:2), Mar/Apr 1987.

- Queries and Comments: Human Sacrifice and Circumcision, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:2), Mar/Apr 1987.

- The Saga of Eliashib, Anson F. Rainey, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:2), Mar/Apr 1987.

- King Solomon’s Wall Still Supports the Temple Mount, Ernest-Marie Laperrousaz, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:3), May/Jun 1987.

- The Jerusalem Wall That Shouldn’t Be There, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:3), May/Jun 1987.

- Cult Stands, LaMoine F. DeVries, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:4), Jul/Aug 1987.

- Temple Architecture, Volkmar Fritz, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:4), Jul/Aug 1987.

- The United Monarchy: Rereading the Bible and the Archaeological Evidence, Lawrence H. Schiffman

Videos

- The Archaeological Treasures Recovered from Illegal Construction on the Temple Mount

- King Hezekiah’s Seal Impression Found in the Ophel Excavations, Jerusalem

- Evidence of the Assyrian Siege at Lachish

- Tel Dan Stele – Evidence of King David?

- Evidence of the Babylonian Destruction of Jerusalem

- City of David Videos

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website