Moving Stones with Muscle Power

Had it not been for the self-promotion of King Sennacherib, who left an exhaustive record of his exploits and deeds chiseled in stone at his palace in Nineveh, scholars today would be hard-pressed to determine just how the ancient Assyrians quarried, worked, and transported the multiton blocks of limestone that they used in creating their winged guardians.

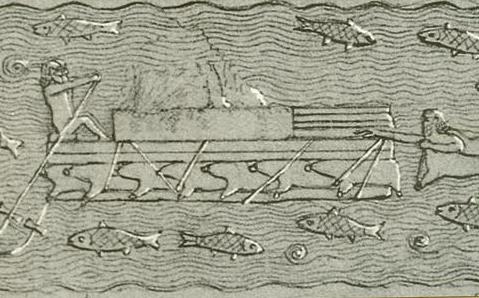

Happily, however, Sennacherib chronicled steps in the making of a bull colossus in a series of reliefs that were discovered in 1849 by Henry Layard in the king’s palace. These reliefs show everything- from the laborers proceeding to the quarry to the cutting of the great stone block and the hauling of the partially sculpted statue to the palace. Once the stone arrived at its destination, the final carving was done. The drawings reproduced here were made from the reliefs themselves.

Supplementing the king’s remarkable pictorial lessons are his cuneiform accounts-some inscribed on the bull-colossi bellies and between their hind legs-that describe in detail the types and sources of stone used. From such written evidence, researchers have learned that Sennacherib tapped a quarry in nearby Balatai, eschewing an older one at Tastiate across the Tigris, and thus forgoing a risky river journey for the stones. His father, Sargon II, is known to have lost at least one colossus to the river’s unpredictable floodwaters.

Straining to pull the monolith out of the quarry pit, four teams of laborers haul on massive ropes attached to the wooden sledge used to carry a winged bull. King Sennacherib himself is seen superintending the operation from the comfort of his chariot, shaded by a parasol.

The heavily laden sledge moves wearily across dry land, nudged along by a crew of laborers plying a long wooden lever. Workers in the front place rollers under the vehicle in order to ease its passage, while King Sennacherib’s supervisors, walking upon the colossus, direct the proceedings.

Mesopotamia- The Mighty Kings. Time-Life Books, 1995. pp. 114-115.