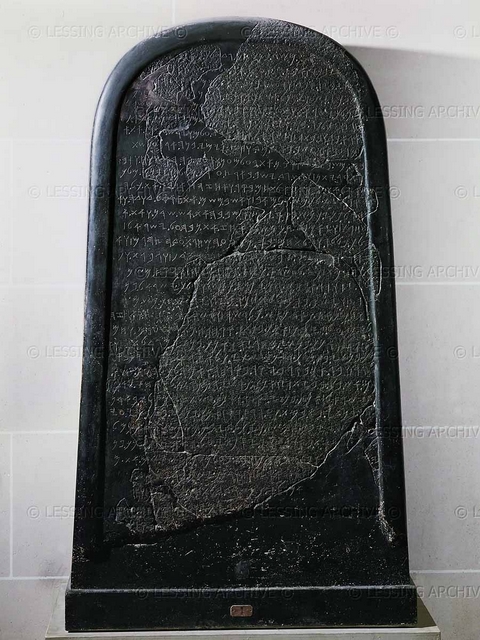

Moabite Stone, c. 840 BCE

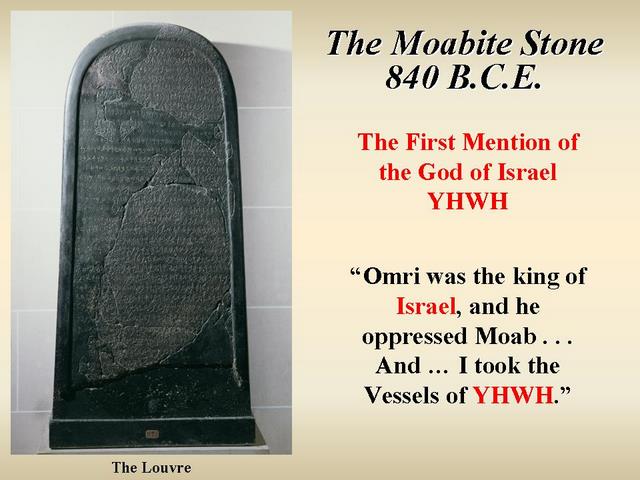

The First Mention of the God of Israel YHWH — “Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab…

And…I took the vessels of YHWH

I am Mesha, son of Kemosh[-yatti], the king of Moab, the Dibonite. My father was king over Moab for thirty years, and I became king after my father. And I made this high-place for Kemosh in Qarcho . . . because he has delivered me from all kings, and because he has made me look down on all my enemies. Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Kemosh was angry with his land. And his son reigned in his place; and he also said, “I will oppress Moab!” In my days he said so. But I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has been defeated; it has been defeated forever!…And I took from there the altar-hearths of Yahweh, and I dragged them before Chemosh. And the king of Israel built Jabaz and dwelt in it while he fought with me and Chemosh drove him out from before me. And I took from Moab two hundred men, all its chiefs, and I led them against Jahaz and took it to add unto Dibon.

Date- c. 840 BCE

Current Location- The Louvre, Paris, France

Language and Script- Moabite; alphabetic

4Now Mesha king of Moab was a sheep breeder, and he had to deliver to the king of Israel 100,000 lambs and the wool of 100,000 rams. 5But when Ahab died, the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel. 6So King Jehoram marched out of Samaria at that time and mustered all Israel. 7And he went and sent word to Jehoshaphat king of Judah, “The king of Moab has rebelled against me. Will you go with me to battle against Moab?” And he said, “I will go. I am as you are, my people as your people, my horses as your horses.” 8Then he said, “By which way shall we march?” Jehoram answered, “By the way of the wilderness of Edom.” 9So the king of Israel went with the king of Judah and the king of Edom…26When the king of Moab saw that the battle was going against him, he took with him 700 swordsmen to break through, opposite the king of Edom, but they could not. 27Then he took his oldest son who was to reign in his place and offered him for a burnt offering on the wall. And there came great wrath against Israel. And they withdrew from him and returned to their own land. (2 Kings 3)

General Information-

The Mesha Stele, made of black basalt and standing nearly 4 feet tall, contains an inscription dictated by King Mesha of Moab, a contemporary of Kings Omri and Ahab of Israel. Located in Transjordan, roughly opposite the territory of Judah, the Moabites were somewhat closely related to the Israelites, one of their many territorial adversaries. The Moabite language, as demonstrated in the inscription, is very similar to Biblical Hebrew, possibly even a dialect of it. Known as the Moabite Stone or the Mesha Stele, this monument contains the longest royal inscription from Iron Age Palestine that has yet been discovered. The inscription begins in the common fashion of Ancient Near Eastern royal monumental inscriptions by speaking in the name of the king, proclaiming, “I am Mesha, King of Moab,” and continues to describe the triumph of Moab’s rebellion against the dominion of the kingdom of Israel. The stele is dedicated to the Moabite god Kemosh for delivering Moab from Israel and probably once stood in a temple of Kemosh at Dibon, Mesha’s capital.

Relevance to Ancient Israel-

• The Mesha Stele provides direct textual evidence that corroborates a story in the Bible (2 Kings 3-4–27). Even though the Bible and the Mesha Stele provide different accounts of the ongoing troubles between Israel and Moab, the fact that both sides describe a struggle indicates that it did in fact occur. According to the Bible, during the war with Israel the king of Moab sacrificed his firstborn son; the Mesha Stele does not. The Stele reports the capture of Israelite territory and the slaughter of thousands of Israelites, which the Bible omits. They agree that after the mid-ninth century BCE, Israel’s power over Moab declined.

• The Mesha Stele allows us to investigate, from an extra-Biblical perspective, what similarities or differences there may have been between Israel and Moab.

- They seem to have shared a common theological perspective on international affairs. Both peoples believed that political misfortune was caused by the anger of their particular national gods (see Judges 3-7–11 for a succinct example) and that deliverance as well as punishment comes from the deity. It is no surprise that the king of Moab bears the name Mesha`, which means “salvation,” just like the names Joshua (Yehoshua’- “God saves”) and Jesus (Yeshu- “He will save”).

- Another socio-religious connection is that both the Israelites and the Moabites had laws that could place a town under a ban of holy war (see Deuteronomy 20-16–17). In such an instance, all spoils of war, both human and material, were dedicated to the deity, who ensured victory in return. The Mesha Stele implies this since Mesha claims that when he captured the town of Nebo from Israel, he dragged the vessels of Yahweh before Kemosh, symbolizing the triumph of Kemosh (see also 1 Samuel 5-1–2).

• Other important features of the stele include an early reference to Yahweh as God of the Israelites and, according to Bible scholar André Lemaire who recently reexamined the Mesha Stele, it appears to mention the “House of David,” the same designation given to the kingdom of Israel in the Tel Dan Stele.

Circumstances of Discovery and Acquisition- F. A. Klein, an Alsatian missionary traveling in Transjordan (modern Jordan) in 1868, spotted the stele in the possession of Bedouin living near Dibon. Before the stele was finally purchased, a drawn-out process that took several years to complete, the Bedouin became suspicious. Not understanding the stele’s historical value, they assumed that there must be a treasure inside it, so they cracked it open it by heating the stele and then pouring cold water over it. What remains of the original block are two large pieces and eighteen smaller fragments. Fortunately, a squeeze had been made of the inscription before it was broken, enabling a substantial restoration, with large hunks of plaster filling the gaps so that it stands as one piece. Today it is on display in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

See also-