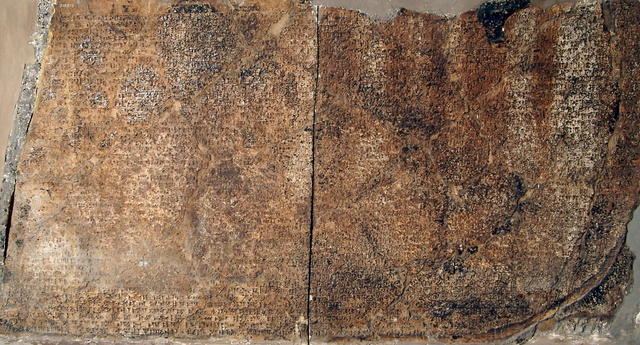

The Annals of Sennacherib on the Nineveh Bulls, 694 BCE

One of the Earliest References of the Word “Jew” (Citizen of Judea)

“As for Hezekiah, the Jew, who had not submitted to my yoke, 46 of his strong, walled cities and the cities of their environs, which were numberless, I besieged, I captured, I plundered, as booty I counted them. Him, like a caged bird, in Jerusalem, his royal city, I shut up. Earthworks I threw up about it. His cities which I plundered, I cut off from his land and gave to the kings of Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gaza; I diminished his land.”

Date- 694 BCE

Current Location- British Museum, London

Language and Script- Assyrian?; cuneiform

Biblical Verses- 2 Kings 18-13–19-18; Isaiah 36-1–37-8; 2 Chronicles 32-1–22

In the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah, King Sennacherib of Assyria marched against all the fortified towns of Judah and seized them. (2 Kings 18-13)

General Information-

• An impressive feature of Neo-Assyrian architecture is the colossal winged bull or lion with a human head, known as a lamassu, which we met when discussing the Kalah bulls. Like other Neo-Assyrian royal palaces, the main doorways in Sennacherib’s “Palace without Rival” were guarded by a pair of lamassi, each inscribed with a copy of the king’s annals. The text is in four sections that are usually arranged as follows- facing the lamassi, the first section is underneath the left bull’s belly, the second between its back legs, and the third and fourth sections are between the right bulls back legs and underneath its belly, respectively. The annals section of the inscription includes Sennacherib’s first five campaigns to the west and the beginning of the sixth. Similar inscriptions were discovered in other doorways to Sennacherib’s throne room, but these were copied and left in situ.

• In the palaces of Ashurnasirpal and Sargon, each lamassu had five legs so that it could be viewed in full perspective from both the front and the side. In the “Palace without Rival,” this fifth leg was eliminated, allowing more space for the inscriptions. The inscription was taken from the pair of bulls guarding the main entrance to the throne room in the “Palace without Rival.”

Relevance to Ancient Israel- Of Sennacherib’s eight military campaigns, the most interesting one for biblical scholars is the third one, in 701 BCE, that was partially against Judah and its king, Hezekiah (2 Kings 18–19). Sennacherib’s aim was to quell a revolt in his western provinces centered in the Philistine city of Ekron. The revolt was fomented by Hezekiah and the Phoenician king Luli, and supported by Sidqia of Ashkelon, another main Philistine city. Sennacherib struck first at Tyre, the Phoenician capital, forcing Luli to flee to Cyprus, where he died. After destroying Ashkelon, further down the Mediterranean coast, the Assyrian army marched into Judah, laid siege to Lakhish and Jerusalem, and eventually cowed Judah into giving a large tribute from the treasuries of the King and Temple. Some early editions of Sennacherib’s annals date to 700 BCE, less than a year after his third campaign occurred, and describe Hezekiah’s tribute in greater detail than the later editions. The earliest known account of this campaign is on the Rassam Cylinder. Archaeologists discovered four well-preserved copies of this barrel cylinder in the foundations of Sennacherib’s “Palace without Rival.” The British Museum also has fragments of dozens of other copies, which likely come from there as well. The foundation work for the “Palace without Rival” was completed in 700 BCE and it seems that numerous copies of Sennacherib’s annals were placed in it.

Circumstances of Discovery and Acquisition- Austen Henry Layard conducted preliminary excavations at Tel Kuyunjik in the summer of 1846. In May and June of 1847, he conducted more extensive excavations there and completely exposed the walls in several rooms of the “Palace without Rival,” including the throne room. The inscription pictured here was cut out from beneath the bulls and sent to the British Museum.