Sephardic Diaspora-Regional Trends

Spanish Jews migrated from the Iberian Peninsula well before the expulsion of Spain’s Jews in 1492. But it was the massive migration at the time of the expulsion that created the foundations of the commercial, kinship, and cultural network we know as the “Sephardic diaspora.” This diaspora was maintained over many centuries, but it changed dramatically over time. Our task here is to look at its configuration in the late fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries.

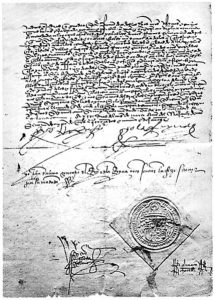

The Expulsion of 1492 was one of the most traumatic events of medieval Jewish history. The Jews of Spain were taken by surprise by the expulsion decree (it was signed on March 31, 1492, but promulgated only a month later) that they were being given only a few months to leave the Spanish kingdoms. By the end of August, there were no openly practicing Jews on Spanish soil, outside the tiny kingdom of Navarre. Many baptized Jews (or descendants of baptized Jews), known as “conversos” or “New Christians,” remained in Spain. In time they, too, were to play a part in the expansion of the Sephardic diaspora.

Let’s look briefly at the background to the Expulsion. This radical measure was adopted in large part because of the ambiguous religious character of the converso population that was created following mass riots in 1391 against Jews throughout Castile and Aragon. This onslaught led to the forced baptism of many of Spain’s Jews – sometimes entire communities. Spanish Christian society did nothing to help assimilate these “New Christians.” And in any case, many of these men and women regarded themselves as Jews and had no wish to be assimilated. In time, discriminatory measures (including “purity of blood” statutes) were imposed, making it difficult for any person with Jewish ancestry (even to a minor degree) to lose the inferior status of “New Christian.” Old Christian hostility to the conversos was partly ethnic (or quasi-racial). But it was invariably justified by the fact that many (though by no means all) of the conversos held on to their Jewish identity, and sought secretly to observe Jewish practices.

It was to rid Spain of such secret judaizing that the notorious Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478. This institution was soon punishing and, especially in the early period, burning at the stake conversos who were convicted of judaizing. But it also brought enormous attention to judaizing activities, real or imputed, among conversos. The Inquisition’s trials also publicized the fact that Jews sometimes aided conversos in their observance of Judaism.

It was with the aim of ridding the Spanish kingdoms of crypto-Jewish heresy that the joint monarchs of Aragon and Castile, Ferdinand and Isabella, decided – with much pressure from the mendicant orders – to expel the Jews, whose continuing presence, they believed, sustained judaizing practices among the conversos. There were undoubtedly other reasons for the expulsion as well – increasing popular anti-Jewish sentiments, the growing influence of the Inquisition at court, and the desire to create national unity – but there is no reason to doubt that the primary motive, as expressed in the decree, was to isolate the conversos entirely from unbaptized Jews.

The Catholic monarchs attempted to carry out the expulsion in as orderly a fashion as possible. But they acted quickly, without considering the basic human needs of the large population they were uprooting. The decree sets forth the conditions in detail. All Jews were required to leave the Spanish kingdoms by July 31, regardless of difficulties- the very old and the very young, the infirm, the pregnant women. The exiles could not plan the most favorable destination to seek; they were often forced to take any route available. The decree also presented them with material difficulties- though they had permission to take their possessions with them, they were not permitted to take the most easily transportable valuables – precious metals and stones. And within three months they were to sell their houses and lands as well as liquidate their businesses, which inevitably drove the prices of properties down.

Given the choice to convert to Christianity or to prepare to leave Spain immediately, many Jews hesitated. The Catholic Monarchs took advantage of the confusion to encourage conversion. Aid and protection, as well as a period of immunity from inquisitorial investigation, were offered to those who would convert. A campaign was undertaken by the mendicant friars to persuade the Jews to convert. This campaign, and the general demoralization of the Jewish population, had their effect- in Teruel, during one day alone, nearly a hundred Jews accepted baptism.

For the many who refused to convert, the choices for flight were limited. Large numbers headed for the major port cities of Spain, in order to embark on ships headed for foreign shores. The most favorable destination, if one could afford to get there, was the Ottoman Empire, where large Sephardic communities soon sprang up. But many exiles went to any destination they could reach. These destinations were almost invariably in the Mediterranean region. Very few of the exiles settled in northern Europe, since Jews were largely prohibited from settling there, and even where they could settle, in certain German towns, conditions were extremely unfavorable. Then, too, it was largely Mediterranean ships on Mediterranean routes that plied the coasts of Spain searching for human cargo. And finally, to the degree that the exiles were able to choose, the Mediterranean region was attractive because of the existing Jewish communities scattered throughout it. When the exiles reached such communities, often traumatized and bereft of the belongings they had been able to take with them, local Jews could provide for their needs.

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website