The Americas

Spanish and Portuguese New Christians were particularly active in colonial commerce in Spanish America. They specialized in bringing luxury goods to Spaniards in the booming mining towns of New Spain and the Viceroyalty of Peru. Crypto-Jews may have felt safer from religious persecution in the vast colonial territories of the Crown, whose governance was much less tightly controlled than in the Peninsula and where the Inquisition was not established until much later. Yet bishops had the authority to prosecute heresy in the absence of an inquisitorial tribunal; and by 1528 New Spain had witnessed its first auto-da-fé. Tribunals of the Inquisition were first introduced in Lima in 1570, to eliminate heresy in the viceroyalty of Peru; the in 1571 in Mexico City, for the viceroyalty of New Spain; and in 1610 in Cartagena, for the viceroyalty of New Granada. The trial documents of these tribunals provide remarkable insight into the earliest expressions of Jewish life (by necessity, crypto-Jewish life) in the Americas.

New Christians were also active in the colonial life of Portuguese Brazil. In 1502 a consortium of New Christians was granted a concession to exploit the new territory, and its members began exporting brazil wood, valued in Europe for the dye produced from it. New Christians also became active as owners and managers of Brazilian sugar mills once this industry was established in the 1540s.

But there was no openly Jewish community in the Americas until the West India Company, aided by the Dutch government, captured northeast Brazil from the Portuguese in 1630 – a military enterprise in which Jews participated. The States General of the Dutch Republic proclaimed that the liberty of Spaniards, Portuguese, and natives in the newly-conquered territory, whether they were Roman Catholics or Jews, would be respected. By 1636 a synagogue had been established in Recife. The opportunities for profit in the sugar industry, tax farming, and the slave trade brought Amsterdam Jews to Dutch Pernambuco in significant numbers, so that the community was soon in need of rabbis and other communal functionaries.

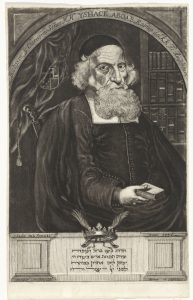

By 1642 two congregations had been established, Zur Israel in Recife and Magen Abraham in Mauricio, and the eminent Amsterdam rabbis Isaac Aboab da Fonseca and Moses Raphael d’Aguilar arrived to serve their needs. The community reached the peak of its growth in 1645, when it comprised perhaps half of the European population of Dutch Brazil, and numbered about 1,500 persons. However, warfare between the Dutch and the Portuguese broke out that year, ending with the defeat of the Dutch in early 1654. During the war many of the Jews of Pernambuco were killed or returned to Amsterdam, while others

settled in the Dutch Caribbean, particularly in Curação and Suriname. Some even settled for a time in French Martinique and Guadaloupe, where a small number of Dutch Jews who engaged in trade and the sugar industry were already tolerated by the French. A group of 23 of the exiles from Dutch Brazil arrived in New Amsterdam (today New York but then ruled by the Dutch), and founded one of the first Jewish communities in North America. At about the same time, the first Jewish settlement in the English colonies was established in Newport, Rhode Island. Sephardic congregations were subsequently established in Charleston, Savannah, and Philadelphia.

Secondary Sources

- Alberro, Solange. “Crypto-Jews and the Mexican Holy Office in the Seventeenth Century,” in P. Bernardini and N. Fiering, eds., The Jews and the Expanion of Europe to the West, 1450-1800, New York and Oxford 2001, 203-212.

- ‘Esposito, Francesco. “Portuguese Settlers in Santo Domingo in the Sixteenth Century (1492-1580).” Journal of European Economic History (1998)

- Israel, Jonathan. “The Jews of Dutch America,” in P. Bernardini and N. Fiering, eds., The Jews and the Expanion of Europe to the West, 1450-1800, New York and Oxford 2001, 335-349.

- Kaplan, Yosef. “The Curaçao and Amsterdam Jewish Communities in the 17th and 18th Centuries,” American Jewish History 72 (1982), 193-211.

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website