“And it was so, when the king saw Esther the queen standing in the court, that she obtained favor in his sight. And the king held out to Esther the golden scepter that was in his hand. So Esther drew near, and touched the top of the scepter”

“And it was so, when the king saw Esther the queen standing in the court, that she obtained favor in his sight. And the king held out to Esther the golden scepter that was in his hand. So Esther drew near, and touched the top of the scepter”

(Esther 5-2).

As we read in the Book of Esther, the queen was able to approach King Ahasuerus unannounced and, as a result of this audience, Esther eventually saved her people.

The Bible refers to scepters on several occasions as symbols of authority and office (for example, Numbers 24-17; Psalm 45-6; Isaiah 14-5; Zechariah 10-11). The reference in Esther, however, is the only time the top of the scepter is specifically mentioned. What did the “top of the scepter” that Queen Esther touched look like? From the text we have no idea, although we are told that it was made of gold.

The Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion has been digging at Tel Dan, in northern Israel, since 1974. Recently we uncovered the top, or head, of a bronze scepter that we believe resembled the gold scepter referred to in the book of Esther.

Dan was the northernmost site in the Biblical kingdom of Israel referred to in the often mentioned Biblical phrase “from Dan to Beer-Sheva.” During the last two decades, we have revealed many remarkable finds,a not the least of which is the religious sanctuary located on the northern part of the city near a spring that is of one of the sources of the Jordan River. Here King Jeroboam of the northern kingdom of Israel set up a golden calf as an alternative to the kingdom of Judah’s Jerusalem temple (1 Kings 12-26–30). Here we found the bilingual Aramaic and Greek inscription “To the God who is in Dan.” Here, too, in a room of a long building we excavated, we found a 3-foot-square altar built of five stones. Nearby three iron shovels or censers used for incense or to remove ashes in a cultic ceremony came to light. Between one of the shovels and the altar lay a jar full of ashes. Analysis of these ashes showed them to be the remains of incense and unidentifiable animal bones.

These finds were described for BAR readers in 1987.b Shortly after this article appeared, we decided to remove the stones of the altar in order to exhibit them in Jerusalem in our Skirball Museum for Biblical Archaeology. Naturally, we also wanted to see if there was anything beneath the altar. Beneath the stones of the altar we discovered a unique object- the head of a scepter!

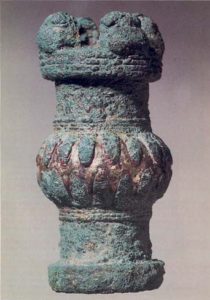

The scepter head is 3.7 inches high and 1.5 inches in diameter. Made of bronze and hollow in the center, it weighs a little less than a pound—14 ounces to be exact.

Around the central part of the scepter head a ring of bronze in the shape of leaves encloses a silver surface. Four badly corroded protrusions on top have been identified as lion heads. Below the lion heads three circular grooves form four veins, or rings, a motif that appears three more times on the scepter head. A flange encircles the bottom of the scepter head.

You can imagine the excitement not only of the students, but of the staff as well, at making such a find. We held in our hands the head, or top, of a scepter that must have been similar to those held by kings and priests in antiquity. It was then that we thought that our scepter might well resemble the top of the scepter Queen Esther had touched, although ours is made of bronze, not gold, and dates to the ninth century B.C.E.,c a few centuries before the Esther story.

Scepter heads have been found in a number of excavations. In some of the older excavations, they were misinterpreted as feet of furniture. Some especially significant scepter tops were discovered by Henry Layard in 1850 in the northwest palace of Nimrud in Mesopotamia. These scepter tops were also made of bronze, sometimes inlaid with iron. Inscribed names appeared on four of them.1

It is possible that a name—or something else—is inscribed on our scepter head. We will know for sure only after experts remove the corrosion on the scepter head and complete their laboratory analysis.

Scepters appear most commonly in ancient texts and glyptic art as symbols of earthly rulers, but in at least one case a cylinder seal displays a scepter in the hand of a goddess.2 Because our scepter head was found beneath an altar we can speculate that it may have belonged to a priest at Dan. Perhaps future finds will substantiate this conjecture.

a. “Danaans and Danites—Were the Hebrews Greek?” BAR 02-02; “Is the Cultic Installation at Dan Really an Olive Press?” BAR 10-06; “King David as Builder,” BAR 01-01; John C. H. Laughlin, “The Remarkable Discoveries at Tel Dan,” BAR 07-05.

b. Hershel Shanks, “BAR Interview- Avraham Biran—Twenty Years of Digging at Tel Dan,” BAR 13-04.

c. B.C.E. is the scholarly, religiously neutral designation equivalent to B.C. It stands for “before the common era.”

1. See R. D. Barnett in Eretz Israel, vol. 8 (Jerusalem, 1967), p. 4ff.

2. James A. Pritchard, The Ancient Near East in Pictures (Princeton, NJ- Princeton Univ. Press, 1954), p. 222.