THESE WERE THE ARAB GANGS THAT, WITH THE AID OF TECHNICALLY SKILLED DESERTERS FROM THE BRITISH ARMY, IN RECENT MONTHS HAD BLOWN UP THE PALESTINE POST AND THE JEWISH AGENCY BUILDING, BOMBED BEN YEHUDA STREET, THE PRINCIPAL JEWISH BUSINESS THOROUGHFARE, AND LAID MINES. As I strolled about I could see that they were in an extremely cocky and festive mood. They had made this last week in March a black week for the Jews. With foolhardy courage, the Haganah had sent a large convoy to supply Kfar Etzion—a chain of four kibbutzim—perched on a strategic hilltop commanding the road to Jerusalem from the south. The convoy had successfully charged through a fifteen mile gauntlet of Arab villages and numerous roadblocks, mines, and snipers’ posts.

THESE WERE THE ARAB GANGS THAT, WITH THE AID OF TECHNICALLY SKILLED DESERTERS FROM THE BRITISH ARMY, IN RECENT MONTHS HAD BLOWN UP THE PALESTINE POST AND THE JEWISH AGENCY BUILDING, BOMBED BEN YEHUDA STREET, THE PRINCIPAL JEWISH BUSINESS THOROUGHFARE, AND LAID MINES. As I strolled about I could see that they were in an extremely cocky and festive mood. They had made this last week in March a black week for the Jews. With foolhardy courage, the Haganah had sent a large convoy to supply Kfar Etzion—a chain of four kibbutzim—perched on a strategic hilltop commanding the road to Jerusalem from the south. The convoy had successfully charged through a fifteen mile gauntlet of Arab villages and numerous roadblocks, mines, and snipers’ posts.

On its way back, however, the story was different. The Jews met Arabs under Abdul Kader el Husseini, a relative of the Mufti, who had served him in the Iraq-Nazi revolt and was now commander of Arab forces in the Jerusalem area. At Nebi Daniel (site of a small Arab village named for the prophet Daniel) huge roadblocks halted the returning convoy. A fierce battle began. Cornered, the Haganah commander regrouped his vehicles on three sides of a square, with a ruined wall forming the fourth side. The battle raged for thirty-six hours between some two hundred Jews and more than three thousand Arabs who had surrounded them and cut them off from all help.

British forces were still responsible for “law and order.” They were in Palestine to prevent precisely such battles as this. But when the British finally intervened, it was to strike a bargain with the Arabs. In return for the safety of the surviving Jews, the Arabs were to take all the Haganah arms and equipment. To prolong a hopeless struggle against odds of fifteen to one would have meant the eventual destruction of the Jewish fighting force as well as the loss of vehicles. The Haganah commander capitulated. The English escorted his men to Jerusalem. To the Jews it meant the loss of almost their entire fleet of armored trucks in Jerusalem. They also lost twelve men. The Arab toll in this “Battle of the Roads” was 135 dead.

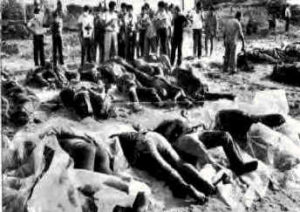

The next day on sale everywhere in the Holy City were gruesome photographs of the battle: the burnt and mutilated bodies of Haganah men, which for some perverse Arab reason, had been stripped of clothing and photographed in the nude. These naked shots hit “Holy” City markets afresh after every battle, and sold rapidly. Arabs carried them in their wallets and displayed them frequently, getting the same weird, abnormal “kick” that our perverts derive from nude photographs of women.

Source: Carlson, John Roy, From Cairo to Damascus. New York, 1951