A few hundred yards from Damascus Gate and over the wall from the Garden Tomb, magnificent burial cave lies beneath a Dominican monastery.

A few hundred yards from Damascus Gate and over the wall from the Garden Tomb, magnificent burial cave lies beneath a Dominican monastery.

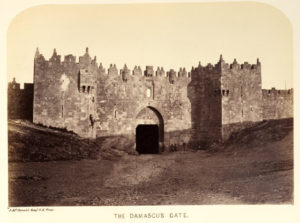

Damascus Gate, the most important entrance to Jerusalem’s Old City, fairly bustles with activity inside and out. Arab men in their robes and keffiyehs; Arab women in long embroidered dresses; priests from a dozen different Christian denominations, Eastern and Western, each with his distinctive gown or collar or hat; Orthodox Jews with long beards and black garb walking to the Western Wall of the Temple Mount to pray; young Israelis; and tourists from everywhere—all mingle and brush shoulders. As a dozen languages blend together, honking taxis and braying mules create a cacophony. Odors typical of Near Eastern bazaars—sweet Turkish coffee, roasted nuts, spices and sheepskin—float through the air.

As its name implies, Damascus Gate opens onto the road to Damascus, 140 miles away. In Hebrew, the gate is called Sha-ar Shechem, Shechem Gate, because the road also leads to Shechem, modern Nablus, on the way to Damascus.

Within a block of the gate, on the right going north, is a large, walled compound—the monastery of the Dominican fathers. Within its walls is not only the Monastery of St. Étienne (St. Stephen), but also the famous École Biblique et Archéologique Française, or the French School, as it is sometimes called.

Read the rest of Jerusalem Tombs from the Days of the First Temple in the online Biblical Archaeology Society Library.