Assyrian national history, as it has been preserved for us in inscriptions and pictures, consists almost solely of military campaigns and battles. It is as gory and bloodcurdling a history as we know.

Assyrian national history, as it has been preserved for us in inscriptions and pictures, consists almost solely of military campaigns and battles. It is as gory and bloodcurdling a history as we know.

Assyria emerged as a territorial state in the 14th century B.C. Its territory covered approximately the northern part of modern Iraq. The first capital of Assyria was Assur, located about 150 miles north of modern Baghdad on the west bank of the Tigris River. The city was named for its national god, Assur, from which the name Assyria is also derived.

From the outset, Assyria projected itself as a strong military power bent on conquest. Countries and peoples that opposed Assyrian rule were punished by the destruction of their cities and the devastation of their fields and orchards.

By the ninth century B.C., Assyria had consolidated its hegemony over northern Mesopotamia. It was then that Assyrian armies marched beyond their own borders to expand their empire, seeking booty to finance their plans for still more conquest and power. By the mid-ninth century B.C., the Assyrian menace posed a direct threat to the small Syro-Palestine states to the west, including Israel and Judah.

The period from the ninth century to the end of the seventh century B.C. is known as the Neo-Assyrian period, during which the empire reached its zenith. The Babylonian destruction of their capital city Nineveh in 612 B.C. marks the end of the Neo-Assyrian empire, although a last Assyrian king, Ashur-uballit II, attempted to rescue the rest of the Assyrian state, by then only a small territory around Harran. However, the Babylonian king Nabopolassar (625–605 B.C.) invaded Harran in 610 B.C. and conquered it. In the following year, a final attempt was made by Ashur-uballit II to regain Harran with the help of troops from Egypt, but he did not succeed. Thereafter, Assyria disappears from history.

We will focus here principally on the records of seven Neo-Assyrian kings, most of whom ruled successively. Because the kings left behind pictorial, as well as written, records, our knowledge of their military activities is unusually well documented-

1. Ashurnasirpal II—883–859 B.C.

2. Shalmaneser III—858–824 B.C.

3. Tiglath-pileser III—744–727 B.C.

4. Sargon II—721–705 B.C.

5. Sennacherib—704–681 B.C.

6. Esarhaddon—680–669 B.C.

7. Ashurbanipal—668–627 B.C.

Incidentally, Assyrian records, as well as the Bible, mention the military contacts between the Neo-Assyrian empire and the small states of Israel and Judah.

An inscription of Shalmaneser III records a clash between his army and a coalition of enemies that included Ahab, king of Israel (c. 859–853 B.C.). Indeed, Ahab, according to Shalmaneser, mustered more chariots (2,000) than any of the other allies arrayed against the Assyrian ruler at the battle of Qarqar on the Orontes (853 B.C.). For a time, at least, the Assyrian advance was checked.

An inscription on a stela from Tell al Rimah in northern Iraq, erected in 806 B.C. by Assyrian king Adad-nirari III, informs us that Jehoahaz, king of Israel (814–798 B.C.), paid tribute to the Assyrian king- “He [Adad-nirari III of Assyria] received the tribute of Ia’asu the Samarian Uehoahaz, king of Israel], of the Tyrian (ruler) and the Sidonian (ruler).”1

From the inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III and from some representations on the reliefs that decorated the walls of his palace at Nimrud, we learn that he too conducted a military campaign to the west and invaded Israel. Tiglath-pileser III received tribute from Menahem of Samaria (744–738 B.C.), as the Bible tells us; the Assyrian king is there called Pulu (2 Kings 15-19–20).

In another episode recorded in the Bible, Pekah, king of Israel (737–732 B.C.), joined forces with Rezin of Damascus against King Ahaz of Judah (2 Kings 16-5–10). The Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III successfully intervened against Pekah, who was then deposed. The Assyrian king then placed Hoshea on the Israelite throne. By then Israel’s northern provinces were devastated and part of her population was deported to Assyria (2 Kings 15-29).

At one point, Israel, already but a shadow of its former self and crushed by the burden of the annual tribute to Assyria, decided to revolt. Shalmaneser V (726–722 B.C.), who reigned after Tiglath-pileser III, marched into Israel, besieged its capital at Samaria and, after three years of fighting, destroyed it (2 Kings 18-10). This probably occurred in the last year of Shalmaneser V’s reign (722 B.C.). However, his successor, Sargon II, later claimed credit for the victory. In any event, this defeat ended the national identity of the northern kingdom of Israel. Sargon II deported, according to his own records, 27,290 Israelites, settling them, according to the Bible, near Harran on the Habur River and in the mountains of eastern Assyria (2 Kings 17-6, 18-11).

Later, in 701 B.C., when King Hezekiah of Judah withheld Assyrian tribute, Sargon II’s successor, Sennacherib, marched into Judah, destroying, according to his claim, 46 cities and besieging Jerusalem. Although Sennacherib failed to capture Jerusalem (2 Kings 19-32–36), Hezekiah no doubt continued to pay tribute to Assyria.

The two principal tasks of an Assyrian king were to engage in military exploits and to erect public buildings. Both of these tasks were regarded as religious duties. They were, in effect, acts of obedience toward the principal gods of Assyria.

The historical records of ancient Assyria consist of tablets, prisms and cylinders of clay and alabaster. They bear inscriptions in cuneiform—wedge-shaped impressions representing, for the most part, syllables. In addition, we have inscribed obelisks and stelae as well as inscriptions on stone slabs that lined the walls and covered the floors of Assyrian palaces and temples.

In all of these inscriptions, the king stands at the top of the hierarchy—the most powerful person; he himself represents the state. All public acts are recorded as his achievements. All acts worthy of being recorded are attributed only to the Assyrian king, the focus of the ancient world.

The annals of the kings describe not only their military exploits, but also their building activities. This suggests that the spoil and booty taken during the military campaigns formed the financial foundation for the building activities of palaces, temples, canals and other public structures. The booty—property and people—probably provided not only precious building materials, but also artists and workmen deported from conquered territories.

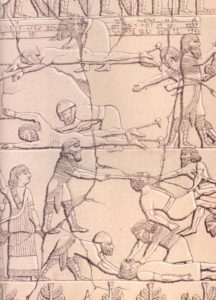

The inscriptional records are vividly supplemented by pictorial representations. These include reliefs on bronze bands that decorated important gates, reliefs carved on obelisks and some engravings on cylinder seals. But the largest and most informative group of monuments are the reliefs sculpted into the stone slabs that lined the palaces’ walls in the empire’s capital cities-Nimrud (ancient Kalah), Khorsahad (ancient Dur Sharrukin) and Kuyunjik (ancient Nineveh).

According to the narrative representations on these reliefs, the Assyrians never lost a battle. Indeed, no Assyrian soldier is ever shown wounded or killed. The benevolence of the gods is always bestowed on the Assyrian king and his troops.

Like the official written records, the scenes and figures are selected and arranged to record the king’s heroic deeds and to describe him as “beloved of the gods”-

“The king, who acts with the support of the great gods his lords and has conquered all lands, gained dominion over all highlands and received their tribute, captures of hostages, he who is victorious over all countries.”2

The inscriptions and the pictorial evidence both provide detailed information regarding the Assyrian treatment of conquered peoples, their armies and their rulers. In his official royal inscriptions, Ashurnasirpal II calls himself the “trampler of all enemies … who defeated all his enemies [and] hung the corpses of his enemies on posts.”3 The treatment of captured enemies often depended on their readiness to submit themselves to the will of the Assyrian king-

“The nobles [and] elders of the city came out to me to save their lives. They seized my feet and said- ‘If it pleases you, kill! If it pleases you, spare! If it pleases you, do what you will!’”4

In one case when a city resisted as long as possible instead of immediately submitting, Ashurnasirpal proudly records his punishment-

“I flayed as many nobles as had rebelled against me [and] draped their skins over the pile [of corpses]; some I spread out within the pile, some I erected on stakes upon the pile … I flayed many right through my land [and] draped their skins over the walls.”5

The account was probably intended not only to describe what had happened, but also to frighten anyone who might dare to resist. To suppress his enemies was the king’s divine task. Supported by the gods, he always had to be victorious in battle and to punish disobedient people-

“I felled 50 of their fighting men with the sword, burnt 200 captives from them, [and] defeated in a battle on the plain 332 troops. … With their blood I dyed the mountain red like red wool, [and] the rest of them the ravines [and] torrents of the mountain swallowed. I carried off captives [and] possessions from them. I cut off the heads of their fighters [and] built [therewith] a tower before their city. I burnt their adolescent boys [and] girls.”6

A description of another conquest is even worse-

“In strife and conflict I besieged [and] conquered the city. I felled 3,000 of their fighting men with the sword … I captured many troops alive- I cut off of some their arms [and] hands; I cut off of others their noses, ears, [and] extremities. I gouged out the eyes of many troops. I made one pile of the living [and] one of heads. I hung their heads on trees around the city.”7

The palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud is the first, so far as we know, in which carved stone slabs were used in addition to the usual wall paintings. These carvings portray many of the scenes described in words in the annals.

From the reign of Shalmaneser III, Ashurnasirpal II’s son, we also have some bronze bands that decorated a massive pair of wooden gates of a temple (and possibly a palace) at Balawat, near modern Mosul. These bronze bands display unusually fine examples of bronze repoussé (a relief created by hammering on the opposite side). In a detail, we see an Assyrian soldier grasping the hand and arm of a captured enemy whose other hand and both feet have already been cut off. Dismembered hands and feet fly through the scene. Severed enemy heads hang from the conquered city’s walls. Another captive is impaled on a stake, his hands and feet already having been cut off. In another detail, we see three stakes, each driven through eight severed heads, set up outside the conquered city. A third detail shows a row of impaled captives lined up on stakes set up on a hill outside the captured city. In an inscription from Shalmaneser III’s father, Ashurnasirpal II, the latter tells us, “I captured soldiers alive [and] erected [them] on stakes before their cities.”8

Shalmaneser III’s written records supplement his pictorial archive- “I filled the wide plain with the corpses of his warriors…. These [rebels] I impaled on stakes.9…A pyramid (pillar) of heads I erected in front of the city.”10

In the eighth century B.C., Tiglath-pileser III held center stage. Of one city he conquered, he says-

“Nabû-ushabshi, their king, I hung up in front of the gate of his city on a stake. His land, his wife, his sons, his daughters, his property, the treasure of his palace, I carried off. Bit-Amukâni I trampled down like a threshing (sledge). All of its people, (and) its goods, I took to Assyria.”11

Such actions are illustrated several times in the reliefs at Tiglath-pileser’s palace at Nimrud. These reliefs display an individual style in the execution of details that is of special importance in tracing the development of military techniques.

Perhaps realizing what defeat meant, a king of Urartu, threatened by Sargon II, committed suicide- “The splendor of Assur, my lord, overwhelmed him [the king of Urartu] and with his own iron dagger he stabbed himself through the heart, like a pig, and ended his life.”12

Sargon II started a new Assyrian dynasty that lasted to the end of the empire. Sargon built a new capital named after himself—Dur Sharrukin, meaning “Stronghold of the righteous king.” His palace walls were decorated with especially large stone slabs, carved with extraordinarily large figures.

Sargon’s son and successor, Sennacherib, again moved the Assyrian capital, this time to Nineveh, where he built his own palace. According to the excavator of Nineveh, Austen Henry Layard, the reliefs in Sennacherib’s palace, if lined up in a row, would stretch almost two miles. If anything, Sennacherib surpassed his predecessors in the grisly detail of his descriptions-

“I cut their throats like lambs. I cut off their precious lives (as one cuts) a string. Like the many waters of a storm, I made (the contents of) their gullets and entrails run down upon the wide earth. My prancing steeds harnessed for my riding, plunged into the streams of their blood as (into) a river. The wheels of my war chariot, which brings low the wicked and the evil, were bespattered with blood and filth. With the bodies of their warriors I filled the plain, like grass. (Their) testicles I cut off, and tore out their privates like the seeds of cucumbers.”13

In several rooms of Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace at Nineveh, severed heads are represented; deportation scenes are frequently depicted. Among the deportees depicted, there are long lines of prisoners from the Judahite city of Lachish; they are shown pulling a rope fastened to a colossal entrance figure for Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh; above this line of deportees is an overseer whose hand holds a truncheon.

Sennacherib was murdered by his own sons. Another son, Esarhaddon, became his successor. As the following examples show, Esarhaddon treated his enemies just as his father and grandfather had treated theirs- “Like a fish I caught him up out of the sea and cut off his head,”14 he said of the king of Sidon; “Their blood, like a broken dam, I caused to flow down the mountain gullies”;15 and “I hung the heads of Sanduarri [king of the cities of Kundi and Sizu] and Abdi-milkutti [king of Sidon] on the shoulders of their nobles and with singing and music I paraded through the public square of Nineveh.16

Ashurbanipal, Esarhaddon’s son, boasted-

“Their dismembered bodies I fed to the dogs, swine, wolves, and eagles, to the birds of heaven and the fish in the deep…. What was left of the feast of the dogs and swine, of their members which blocked the streets and filled the squares, I ordered them to remove from Babylon, Kutha and Sippar, and to cast them upon heaps.”17

When Ashurbanipal didn’t kill his captives he “pierced the lips (and) took them to Assyria as a spectacle for the people of my land.”18

The enemy to the southeast of Assyria, the people of Elam, underwent a special punishment that did not spare even their dead-

“The sepulchers of their earlier and later kings, who did not fear Assur and Ishtar, my lords, (and who) had plagued the kings, my fathers, I destroyed, I devastated, I exposed to the sun. Their bones (members) I carried off to Assyria. I laid restlessness upon their shades. I deprived them of food-offerings and libations of water.”19

Among the reliefs carved by Ashurbanipal were pictures of the mass deportation of the Elamites, together with severed heads assembled in heaps. Two Elamites are seen fastened to the ground while their skin is flayed, while others are having their tongues pulled out.

There is no reason to doubt the historical accuracy of these portrayals and descriptions. Such punishments no doubt helped to secure the payment of tribute—silver, gold, tin, copper, bronze and iron, as well as building materials including wood, all of which was necessary for the economic survival of the Assyrian empire.

In our day, these depictions, verbal and visual, give a new reality to the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel in 721 B.C. and to Sennacherib’s subsequent campaign into Judah in 701 B.C.

1. Stephanie Page, “A Stela of Adad-nirari III and Nergal-eres from Tell al Rimah,” Iraq 30 (1968), p. 143.

2. Albert Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, Part 2- From Tiglath-pileser I to Ashur-nasir-apli II (Wiesbaden, Germ.- Otto Harrassowitz, 1976), p. 165.

3. Grayson, p. 120.

4. Grayson, p. 124.

5. Grayson, p. 124.

6. Grayson, pp. 126–127.

7. Grayson, p. 126.

8. Grayson, p. 143.

9. Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, 2 vols. (Chicago Univ. of Chicago Press, 1926–1927), vol. 1, secs. 584–585.

10. Luckenbill, vol. 1, sec. 599.

11. Luckenbill, vol. 1, sec. 783.

12. Luckenbill, vol. 2, sec. 22.

13. Luckenbill, vol. 2, sec. 254.

14. Luckenbill, vol. 2, sec. 511.

15. Luckenbill, vol. 2, sec. 521.

16. Luckenbill, vol. 2, sec. 528.

17. Luckenbill, vol. 2, secs. 795–796.

18. Luckenbill, vol. 2, sec. 800.

19. Luckenbill, vol. 2, sec. 810.