These three faiths all originate in the Middle East. According to the Torah, Abraham, founder of the Jewish nation, was born in the southern Mesopotamian town of Ur of the Chaldees (now in modern Iraq). By God’s command he then migrated to Canaan, a region corresponding roughly to modern day Israel and Lebanon. Jesus of Nazareth was born in Bethlehem, in Israel, around the year that now defines the beginning of the common or Christian era (CE, AD). The Prophet Muhammad lived in Mecca, in present day Saudi Arabia, until 622 when he led his followers on a journey to Medina called the Hijrah (migration). This event marks the year in which the Islamic calendar begins (AH).

These three faiths all originate in the Middle East. According to the Torah, Abraham, founder of the Jewish nation, was born in the southern Mesopotamian town of Ur of the Chaldees (now in modern Iraq). By God’s command he then migrated to Canaan, a region corresponding roughly to modern day Israel and Lebanon. Jesus of Nazareth was born in Bethlehem, in Israel, around the year that now defines the beginning of the common or Christian era (CE, AD). The Prophet Muhammad lived in Mecca, in present day Saudi Arabia, until 622 when he led his followers on a journey to Medina called the Hijrah (migration). This event marks the year in which the Islamic calendar begins (AH).

From the Middle East each faith spread throughout the world. Some of that geographic diversity is represented specifically in this section. Elsewhere in this catalogue there are manuscripts and other objects from Europe, North and West Africa, the Indian subcontinent and China, as well as from the Middle East.

In addition to geographic diversity is the diversity that comes from within the faiths themselves. Some of the many denominations or sects of each faith are explored here. Jewish manuscripts are particularly prominent in this section, because it is important to set out clearly the different historical strands within Judaism before examining its textual and artistic traditions.

Judaism

In early Jewish history Palestine and Babylonia were the two major centres of religious authority. Each developed a different liturgy, or rite for public worship. In the Middle Ages central and northern European Jews known as Ashkenazi (derived from the Hebrew word for Germany) followed a rite from the Palestinian tradition. The Ashkenazi rite gradually spread to other Jewish communities in Western Europe and far beyond. Jews living in Spain and Portugal, known as Sephardi (from the late Hebrew word for Spain) adopted Babylonian liturgical practices. Sephardi custom spread to North Africa, the Balkans, Holland, Italy, some areas of Germany and Austria, and other parts of the world where Spanish and Portuguese Jews had settled after their expulsion from Spain and Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century. What distinguishes the Sephardi from the Ashkenazi tradition is not the statutory prayers as such, but the order and wording of certain prayers, as well as some differences in liturgical poetry and rituals. Both traditions are consistent with Orthodox Judaism, believing that the Torah was given by God to Moses at Mount Sinai, and combining the written and oral Torah.

Both Ashkenazi and Sephardi traditions are illustrated here- a Pentateuch written in Ashkenazi square script, a printed Sephardic prayer book with some text in Ladino, the language of the Sephardim, and a rare miniature printed Ashkenazi daily prayer book. The wide geographic range and cultural diversity of the Diaspora is particularly apparent from the manuscripts included- a specially prepared Chinese Torah scroll, an Ethiopian Psalter and an impressive Pentateuch, one of the very few Hebrew manuscripts to survive from medieval Portugal.

The second aspect of Jewish life highlighted is the presence of sects and reform movements. Among the earliest of these were the Samaritans, who may have split from mainstream Judaism as early as the fourth century BC, and have continued to the present. The Samaritan example here is a Pentateuch written in Damascus in 1339. Another group of Jews to emerge in the Middle Ages were the Karaites (literally, ‘people of the Scripture). Their distinctive tradition is limited to the written Hebrew Bible alone, illustrated here by a Russian Pentateuch with a translation in the Tatar dialect.

Reform Judaism originated in Germany in the nineteenth century, and denied the divine inspiration of the Torah. Instead, the movement accepted the critical theory that the Bible was written by separate authors, combined over time. Most radically, it totally rejected the idea of a return to Zion and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, as articulated in the Hebrew Bible. This drastic shift was later reversed in the aftermath of the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel.

The first Jewish Reform Temple opened in 1818 in Hamburg, and a copy of its first Reform prayer book is included in this section. The Reform movement in Britain began in 1836, when some members of the Bevis Marks Synagogue in London attempted innovations to both liturgy and worship. Ignored by the synagogue leadership, this group’s determination led ultimately to the founding of the first British Reformed synagogue. The Reform faction in Britain has been more traditionalist than both the nineteenth-century German Reformists and the current Jewish Reform movement in the United States, with which it has no links. Liberal Judaism in Britain is closer in creed and practice to the German and American Reform movements than it is to British Reform Judaism. Its founders in 1902 included Lily Montague, a charismatic aristocrat, and the biblical scholar Claude Montefiore. Like the German Reform movement fifty years earlier, it sought to make radical innovations in worship, with the use of more English in services, musical accompaniment, and equal participation by men and women. What was initially intended as a supplement to the existing Orthodox and Reform services ended up as a newborn religious movement, leading to the creation in 1911 of the first Liberal synagogue in Britain. The Liberal movement tends to embrace a more open outlook, particularly on more challenging and controversial issues. This is illustrated in the modern Liberal prayer book, in the exhibition open to prayers for the United Nations Sabbath, with a prayer for the Lord to bless the United Nations and help it achieve world peace.

Christianity

Christianity today includes a multiplicity of denominations and sects, despite the continuing vitality of the Ecumenical Movement, wide participation in the World Council of Churches, and extensive interdenominational discussions focused on reunion. Some of these divisions occurred in the first centuries of Christianity, during a period in which several important church councils were held to decide complex theological points of doctrine. A sixth-century Syriac copy of ecclesiastical laws formulated at fourth- and fifth-century church councils illustrates some of the decisions taken at these councils. A significant division within Christianity occurred with the so-called ‘Great Schism’ between the Eastern and Western churches, led traditionally from Constantinople and Rome, respectively. Political, ecclesiastical and theological differences developed over the centuries. In 1439 representatives of both churches met in Florence to attempt to resolve the differences, including the vexed questions of whether the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son (‘filioque’) or from the Father through the Son, questions of transubstantiation, purgatory and hell, of papal supremacy, and of the order of precedence among the Eastern patriarchs. This section includes an impressive copy of the papal bull that announced an imposed agreement reached on these issues, complete with the papal authorization and the signature of the Byzantine emperor. However, the union was not subsequently ratified by an Eastern synod, and has never been implemented, resulting in the final breach and continued division between the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches.

Another major split within Christendom illustrated in this section is that between England and Rome. In 1534, after protracted and unsuccessful negotiations with the pope over the proposed annulment of his first marriage, King Henry VIII (r. 1509-47) was declared the head of a new Church of England, repudiating the pope’s authority. The so-called ‘Great Bible’ was printed in London five years later. The king’s new status as head of the English church is dramatically illustrated on its title page, where the king distributes Bibles to his subjects. The Bible also represents another aspect of the English Reformation – the order that every parish should have a large reading copy of the Bible in English.

Islam

After Muhammad’s death in 632, Islam spread rapidly. During the period of the Umayyad caliphate that ruled from Damascus (661-750), Islam spread west from Egypt to Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. It also expanded into the Iberian Peninsula, becoming the dominant power in Spain from 711. A rare thirteenth-century Qur’an from Granada illustrates this period of rule in the West, prior to the Christian Reconquista largely completed by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492. Islam also reached India at an early date (the first mosque was built there during the lifetime of Muhammad). A sixteenth-century Indian patron commissioned the beautiful Qur’an written in gold, black and blue included in this section. Islam in South East Asia is represented by a Malay Qur’an, produced on paper manufactured in Europe. Its expansion through trade is demonstrated by part of a remarkable Chinese Qur’an originally made in thirty volumes, written in a particular script associated with Chinese calligraphy, often referred to as sini, or Chinese Arabic.

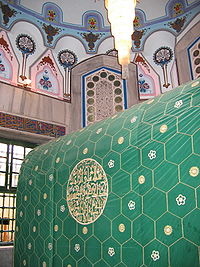

Within Islam, there are two principal divisions. The largest denomination is of Sunni Muslims, who regard the leader or caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632-4) as Muhammad’s rightful successor, chosen by the people. However, Shi’a Muslims recognize the succession of Muhammad’s cousin and son-in law, ‘Ali (r. 656-61). A standard or ‘alam used in the Shi’a processional ceremonies on ‘Ashura, the tenth day of the first month of the Muslim year commemorating the martyrdom of ‘Ali’s son, Husayn, is included in the last section. Sufism is another sect within both branches of Islam, a mystical tradition encompassing a diverse range of beliefs and practices.

Wahhabism is another religious and spiritual reform movement within Islam illustrated by the last manuscript in this section. It is a history of the Najd region in present-day Saudi Arabia, the region where the founder of this movement, Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab, was born in 1703. Based on legal interpretations that are conservative and literal in approach, Wahhabism forbids all practices that might be considered innovations, and rejects, for example, the Sufi custom of venerating saints. Over the generations Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s teachings became the religious force behind the formation of what is today the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Pages 38-39