When he found it, Ofer Broshi was on army duty. Army life can be exhausting or boring—or sometimes both. At that moment, Broshi, a rugged young kibbutznik, was more bored than tired. He was resting on the summit of a hill in northern Samaria, above the ancient road connecting the Biblical towns of Dothan and Tirzah.

When he found it, Ofer Broshi was on army duty. Army life can be exhausting or boring—or sometimes both. At that moment, Broshi, a rugged young kibbutznik, was more bored than tired. He was resting on the summit of a hill in northern Samaria, above the ancient road connecting the Biblical towns of Dothan and Tirzah.

He looked aimlessly at the ground. Then suddenly he saw something staring back at him from beneath the soil. It was obviously not alive. He reached to see what it was, brushing away the dirt that partially covered it. He was startled to discover that the eyes he had seen belonged to a beautiful bronze figurine of a young bull, which he soon held in his hand, turning it every which way in disbelief.

Broshi brought the figurine back with him to his kibbutz. Almost every kibbutz has at least one amateur archaeologist and Kibbutz Shamir of which Broshi is a member was no exception. There kibbutznik and amateur archaeologist Moshe Kagan arranged to have the bull displayed in the kibbutz antiquities collection.

It was there that I first saw it. I immediately recognized its importance and promptly notified the Department of Antiquities. Negotiations between the kibbutz and the Department resulted in the transfer of the bull to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem for study. It is now displayed there in a special showcase. (In exchange, the Department of Antiquities donated various other artifacts of less importance to the kibbutz collection of antiquities.)

But it was equally important to study the context in which the bull had been uncovered. Thanks to Ofer Broshi’s precise information and to the cooperation of the Department of Antiquities, I was able to locate the site and explore it.

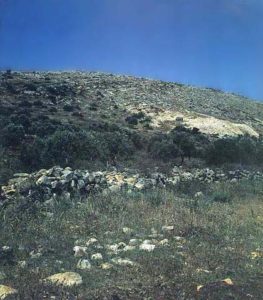

I vividly recall my first visit to the site. It is located on the summit of a high ridge. In the distance I could see the most important ridges in northern Palestine. There to the north were Mount Tabor and Mount Meiron; to the west was Mount Carmel; to the northeast was Mount Gilboa; and to the south was Jebel Tamun.

We commenced a detailed archaeological survey of the ridge but found no remains of an ancient settlement. What we did find on the hill was rather startling—the remains of an ancient cult site!

In a few days of excavation, we were able to expose whatever was left of this cult site, which, although badly damaged by erosion, proved to have important significance for our knowledge of Biblical “high places.”

In the excavation we found a handful of potsherds, the indestructible pieces of pottery which mean so much to archaeologists. We found the rims of some cooking pots, some pieces of rounded bowls, the neck of a flask, some disk bases of shallow bowls. By studying these fragments we were able to date the occupation of the site to the period archaeologists call Iron Age IA—about 1200 B.C.—a time when the Israelite tribes started their permanent settlement of the Land of Israel. Our dating task was made somewhat easier because this was a one-period site. It had been used for only a short time and was then abandoned. Thus, we concluded, the bronze figurine of the young bull was probably used in some religious ritual in the days of the Judges in the land assigned to the tribe of Manasseh.

More exciting than the pottery were the structural remains on the top of the ridge. The structure had been built on bedrock. Most of it had unfortunately eroded away. But enough was left to identify a wall built of large field stones that had once enclosed an elliptical area about 70 feet in diameter.

At the eastern part of the enclosure we found a large stone over four feet long, three feet high, and about one and three-quarters feet thick. It had been worked, but only slightly The sides were left rough and uneven. Nevertheless, it was easy to distinguish this large stone slab from the other largely unworked stones used to build the enclosure wall.

The uneven bedrock in front of the three-foot-high stone had been leveled with a paving of rough flat stones.

The site appears to have been an open-air cult center comprising a massive stone enclosure wall with a large rectangular stone slab set on a special pavement. The stone slab—although wider than it is high—may be identified in Biblical terms as a kind of “standing stone” or massebah (compare Genesis 35-14). Or perhaps it was a kind of altar which stood in front of the pavement of flat stones.

In front of this massebah or altar and on the pavement next to it were other finds. One was a fragment of a bronze object we cannot identify. The fragment includes a folded piece of a flat bronze sheet and part of a handle. It may have been a bronze mirror of the Egyptian type. But the major significance of the piece is that its excellent state of preservation indicates that a bronze object would not corrode in the terra rosa soil of the site. Our bronze fragment thus served to authenticate the finding of the bronze bull figurine at this site.

Among the stones of the pavement, near the massebah or altar, we found a fragment of a pottery object, which originally was part of a square incense burner or similar cult object like those found at Taanach, Megiddo and Beth Shean, or it might possibly have been a model of a cult-shrine such as was found at Tirzah (Tell el-Farah [North]). In either case, this pottery fragment confirms the cultic nature of the site.

Also consistent with this activity are a few remains of some animal bones, possibly from sacrificial animals.

We may assume that at other places in the enclosure, now completely eroded, there were other installations for cultic functions. Perhaps a sacred tree, often mentioned in the Bible in connection with cult places on top of hills and mountains, grew in the center of the enclosure where our excavations uncovered no finds at all (see Ezekiel 6-13).

The bull figurine itself is unique. It is not only the largest bull figurine ever found in Israel—indeed, in the entire Levant—it also combines naturalistic and stylized elements in an unusual way.

The bull is seven inches long and five inches high. It can stand on its feet without support or tang. It was made by the so-called “lost wax” technique. The animal was first created in wax. Then the wax was covered with clay. Several holes were made in the clay cover. Hot molten bronze was then poured into the clay cover through one of these holes. The molten metal naturally melted the wax, which poured out through other holes. What is perhaps the remains of the hole into which the molten bronze was poured can still be seen at the top of the animal’s neck.

The treatment of the legs is clear evidence that the bull was first modeled in wax. Each pair of legs was molded as a separate long strip which was bent above the body of the animal, thus creating a ridge on its body and back, continuing the line of the legs.

The rounded eyes of the animal consist of protruding ridges around depressions which must have once contained inlays of glass or semi-precious stone, thus giving the animal an intense and vivid expression.

Some of the bull’s other features are quite naturalistic. In addition to the eyes, look at the ears and horns. The legs too are quite lifelike. The male organs were sculpted in detail, an indication of power and fertility.

On the other hand, other characteristics are stylized and schematic. The body is rectangular. The breast is a heavy triangle. The neck is flat. The head is triangular from the front, and long and narrow from the side. The mouth is a straight slot at the flat bottom of the head. All these features give the animal a simplistic look.

The small hump on the back of the animal, above its forelegs, enables us to identify the bull as a “Zebu Bull” (Bos indicus), a type which originated in India and reached the Near East as early as the fourth millennium B.C. It is known in various artistic representations from the ancient Near East, and actual bones of such bulls were excavated, for example, at Deir Alla in the Jordan Valley. Our figurine was probably the product of a local, non-professional artisan lacking a defined artistic heritage.

The bull motif itself, however, is extremely common—and therefore extremely important—in Near Eastern iconography. It is a symbol both of power and fertility. Sometimes the bull appears as a cult object itself, for example, as a young striding god to be worshipped as the symbol of the deity. Other times it appears as a depiction of an attribute of the West Semitic storm god Hadad who is known in the Bible as Baal.

There are some examples from the second millennium B.C. of representations showing the worship of a bull as a symbol of a deity. In a famous Hittite relief, a royal couple stands in prayer before a bull on an altar. In another group of artistic depictions, however, the bull appears as the attribute of the storm god Hadad (or Baal). He is sometimes shown holding the bull with reins. In this aspect the bull symbolizes Baal’s strength and power. In other examples we find the storm god standing on top of a bull, the bull serving as a pedestal for the god.

This double aspect of the bull—both as a symbol of a deity itself and as an attribute of the storm god—is important in any attempt to understand the cult of the golden calf in the Bible. Scholars disagree as to the meaning of this cult. Some claim the calf was simply the pedestal of Yahweh, like the cherubim over the Ark of the Covenant in the Jerusalem Temple. If this is true, our bull figurine may have been considered only a pedestal for the god—seen or unseen—worshipped at our site. Others believe the golden calf had a much deeper meaning as a symbol of the god of Israel or even of a foreign deity. Both interpretations are supportable on the basis of the iconographic material.

Was our bull figurine a real cult object in itself, or was it just a votive offering object, symbolizing the strength of the god? Its relatively large size, the great care taken in its manufacture, the inlaid eyes, all suggest that it was a cult object of great importance. Yet we cannot be sure of its exact significance.

From finds at other sites, we know that the Israelites continued Canaanite metallurgical technology and metallurgical traditions during Iron Age I. And, indeed, Israelite metal artisans are referred to in Judges 17-4–5. So our bull figurine may be the product of a local Israelite craftsman inspired by Canaanite traditions, or it may have been obtained by the Israelites through trade with Canaanites in the villages of northern Israel.

What is the basis of the site’s identification as an Israelite cult place? The first thing to note is that the site is not near any major ancient Canaanite city The closest mounds are between four and six miles away However, a series of small Iron Age I sites has been discovered in the vicinity during archaeological surveys of the region. Our site is located in the middle of a cluster of such small sites. These small sites can probably be related to the settlement process by the Israelite tribes in this area. These sites flourished as small agricultural villages and our cultic enclosure probably served as a central ritual place for a group of these settlements. We can thus conclude that Israelites, probably from the tribe of Manasseh, were the builders of this cult site.

Open cult places were a permanent feature of the Israelite cult from patriarchal times until the religious reform of Josiah in the late seventh century B.C. In the patriarchal narratives we find altars (mizbeah) erected by the Patriarchs in the open—close to major cities like Shechem, Bethel, Jerusalem, Hebron and Beer-Sheva. Some of them were erected near a sacred tree (Genesis 12-6–7, Genesis 13-18), and in at least one case, the installation included a sacred stone (massebah) (Genesis 35-14). Such altars were probably simple installations, providing a place for sacrifice or the placing of offerings in a well-defined enclosure. Our cult place is no doubt an illustration of such an ancient “altar” built in the open, outside a group of small settlements. The large stone defined by us as a massebah was part of the cult place, just as the masseboth in the patriarchal narratives. Our example is the earliest known open cult place which may be attributed to Israelites (later ones are known from Arad and Hazor), and it is the only one situated outside a settlement on top of a remote ridge.

The Biblical term bamah (1 Kings 14-23, 2 Kings 17-9–11, 23-13–14), usually translated as “High Place,” should also be mentioned in relation to our site. Although the exact meaning of the term is still open to debate, all agree that the bamah was an open cult place of some sort. It appears in the Israelite cult as early as the time of Samuel and continues throughout the monarchic period until the reform of Josiah. Sometimes the bamah is an open cult place on hills or mountains (1 Kings 14-23; 2 Kings 17-9–11; 23-13–14; 18-20, 29). Sometimes a bamah is mentioned without definite location or is located inside towns. The bamot at Ramah, Gibeah and Gibeon mentioned in connection with Samuel and Solomon show how important these cult installations were at the time. Etymologically the word bamah derives from “body” and, metaphorically, from “mountain ridge,” so the Israelite bamah probably originated in open cult places on tops of mountains of the kind represented by our site. Thus the “altars” of the patriarchal narratives may be related to the later bamot. And our site may exemplify both.

But who was worshipped here? Perhaps Baal. Or perhaps Yahweh. The relation between Yahweh and the bull among the northern Israelite tribes is reflected in the Biblical traditions concerning the golden calf. As you will recall, the northern king Jeroboam set up golden calves at Bethel and Dan after the kingdom divided following Solomon’s death (1 Kings 12-28). Scholars consider the golden calves erected by Jeroboam as a revival of an old practice known among the northern tribes of Israel from their early history. Others suggest that Jeroboam introduced a new cultic practice and that the story of the golden calf at the foot of Mount Sinai in Exodus 32 is anachronistic (written long after the episode it describes) and was intended to legitimize and reinforce the opposition to Jeroboam’s deed. The question of the nature of Israelite religion during this period is a complex one. At least one source in the books of Judges (6-25, where Gideon’s father worshipped Baal at Ophrah) hints at the existence of a Baal cult among the Israelites during the period of the Judges. Thus the identification of the specific cult at our site must remain, for the time being, an open question.

(For further details, see “Cult Site from the Time of the Judges in the Mountains of Samaria,” by Amihai Mazar, in Eretz Israel, Vol. 16, Jerusalem, 1982 [in Hebrew], and a forthcoming article in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research.)