Culture conflict on Judah’s frontier

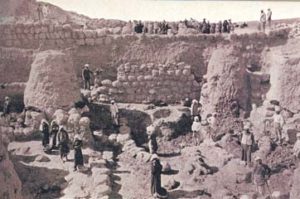

At 6 a.m. on April 6, 1911, a group of Arab villagers headed by a tall, red-haired, boldly mustachioed Scottish highlander named Duncan Mackenzie began to unearth a desolate hillock in Palestine believed to be Biblical Beth-Shemesh.

At 6 a.m. on April 6, 1911, a group of Arab villagers headed by a tall, red-haired, boldly mustachioed Scottish highlander named Duncan Mackenzie began to unearth a desolate hillock in Palestine believed to be Biblical Beth-Shemesh.

In the spirit of the times, Mackenzie, who had been Sir Arthur Evans’s chief assistant at the excavation of the Palace of Knossos in Crete, wanted to “penetrate to the true heart and inner mystery of Beth-Shemesh.” But after two years, the excavation broke off for lack of funds.1

A quarter century later, from 1928 to 1933, Elihu Grant of Haverford College, just outside Philadelphia, led an American expedition that resumed the excavation and systematically unearthed the whole western half of the tell down to bedrock, dismantling vast portions of the successive “cities” Mackenzie had excavated. Grant published three volumes of excavation reports, but they contain mostly raw, stratigraphically confused descriptions (Grant dedicated the volumes to his brother W.T. Grant of five-and-ten-cent store fame).2

Several years later, a young Biblical archaeologist named George Ernest Wright, who would later become one of the leading members of the profession in America and the excavator of Biblical Shechem, attempted to prepare a final synthesis of the Beth-Shemesh excavation. It was ingenious, but artificial. As Wright himself repeatedly emphasized, only a better-controlled excavation of the site could confirm or disprove many of his tentative conclusions.

And that is why we returned to the site six years ago, in 1990.3

Beth-Shemesh is a prime site for exploring the interaction of different cultures as reflected in the archaeological record. Beth-Shemesh is a border town, located at the meeting point of three of the most important ancient civilizations in Palestine—the Canaanites, the Israelites and the Philistines—whose borders frequently shifted. One of Biblical archaeology’s most challenging tasks is to identify the various regional cultures of the country and to study their interaction. In buffer zones like that around Beth-Shemesh, cultural contacts were common, ideas were exchanged and ethnic boundaries were frequently redefined. This presents the true challenge of the site.

Beth-Shemesh means “House of the Sun,” probably reflecting the fact that a Canaanite temple to the sun god once graced the city. If this thought sparked the imagination of Mackenzie, digging on behalf of the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund, or Grant, with his Haverford College expedition, their hopes were dashed. No such temple has been found. But a wealth of other information, some almost as dramatic, provides compensation enough.

Beth-Shemesh was first identified by the American orientalist Edward Robinson, traveling with his friend Eli Smith in the mid-19th century. This odd pair, one a Biblical scholar and the other fluent in Arabic, identified hundreds of Biblical sites, mostly based on the persistence of linguistic elements of the Biblical names in contemporary Arabic toponyms. Such was the case with Beth-Shemesh. A desolate hill known as Rumeillah lay adjacent to an Arab village called ‘Ain Shems (Well of the Sun). Here the site’s ancient name was preserved.4

The identification was confirmed by geography. Located about midway between the Mediterranean and Jerusalem, the site sits high on the south bank of the Nahal Sorek. This places Beth-Shemesh in the foothills of Judah known as the Shephelah, between the Mediterranean coastal plain and the hill country of central Canaan.5 Beth-Shemesh lies opposite Zorah, Samson’s birthplace, and from the site we can look down the Valley of Sorek all the way to Timnah (Tel Batash), where Samson was smitten with a Philistine girl whom he insisted on marrying despite his parents’ objections (Judges 14-1–3). There Samson propounded his famous riddle- “Out of the eater came something to eat, / Out of the strong came something sweet” (Judges 14-14).

Although Beth-Shemesh is not mentioned by name in any extra-Biblical sources, it plays a prominent role in the Bible. A popular round stone pilgrim platform now sits atop the site of Beth-Shemesh, and from this vantage point it is easy to imagine the Ark of the Covenant returning to Israel from Philistine territory. You will recall that the Philistines captured the Ark at the battle of Ebenezer (1 Samuel 4-11). It did them no good, however; indeed, it caused them all sorts of difficulties, not the least of which was painful hemorrhoids (1 Samuel 5). On the advice of their priests and diviners, the Philistines loaded the Ark together with a guilt offering of five golden mice and five golden images of hemorrhoids on a new wooden cart harnessed to two milk cows that had never been yoked and sent it off aimlessly. The question was whether the cows would proceed to Israelite territory, thus indicating that the Lord of Israel had brought misfortune to the Philistines, or would remain within Philistine territory. According to the Bible, “The cows went straight in the direction of Beth-Shemesh along one highway, lowing as they went; they turned neither to the right nor to the left, and the lords of the Philistines went after them as far as the border of Beth-Shemesh” (1 Samuel 6-12). From this passage, one may assume Beth-Shemesh was the first city inside Israelite territory.

When the cart with the Ark arrived at Beth-Shemesh, the people were reaping their wheat. “When they looked up and saw the Ark, they went with rejoicing to meet it. The cart came into the field of Joshua of Beth-Shemesh and stopped there. A large stone was there; so they split up the wood of the cart and offered the cows as a burnt offering to the Lord” (1 Samuel 6-13–14). Mackenzie believed that a sheikh’s tomb (called a weli), standing at the point where the road climbs up from the valley and reaches the eastern edge of the tell, had been built next to the great stone mentioned in the Bible.

In Israelite tribal lists Beth-Shemesh is included in the allotment to the tribe of Dan (Joshua 19-41) but is also described as a town on the northern boundary of Judah (Joshua 15-10) and as a Levitical city of refuge in Judah (Joshua 21-16). The town is also mentioned as part of Solomon’s second administrative district (1 Kings 4-9). Israel’s King Jehoash defeated Judah’s King Amaziah during a critical battle in a civil war fought at Beth-Shemesh at the beginning of the eighth century B.C.E. (2 Kings 14-8–14).

The last Biblical reference to Beth-Shemesh reports that during the reign of Hezekiah’s father Ahaz (second half of the eighth century B.C.E.), “the Philistines had made raids on the cities in the Shephelah and the Negev of Judah, and had taken Beth-Shemesh, Aijalon, Gederoth, Soco with its villages, Timnah with its villages, and Gimzo with its villages; and they settled there” (2 Chronicles 28-18).

But the Bible, being a primarily theological work, leaves many historical gaps, often providing mere hints at major political, ethnic and cultural transformations. Archaeology must try to fill these gaps.

Digging before modern methods of excavation had been developed, Mackenzie committed what would today be considered an archaeological sin- He trenched along a massive wall at the edge of the tell, thus destroying the debris stratigraphy associated with the wall and that would have allowed it to be dated. Where he could not easily trench, he tunneled—to the same effect. But he did trace this massive wall of great rough blocks of stone. He called it the “Strong Wall.” He also exposed a well-preserved gateway in this wall on the south side of the mound. Mackenzie identified the wall and its gate as Canaanite, but, influenced by his former investigations of megalithic structures east of the Jordan, he was sure that the art of fortification was first taught to the Semites by “megalithic people.”

Mackenzie identified three “cities,” one on top of the other. With the aid of material from Grant’s excavation, Wright identified six strata—from the Early Bronze Age IV (c. 2000 B.C.E.) through the Late Roman period.

More than 60 years have passed since Grant’s expedition to Beth-Shemesh, a period that has seen enormous strides in excavation techniques as well as in our knowledge of ancient societies. Recent excavations just west of Beth-Shemesh at Timnah/Tel Batash (a small field town) and Ekron/Tel Miqne (a member of the Philistine pentapolis) have brought to light a wealth of information concerning the history, economy and daily life of this region. However, to integrate Beth-Shemesh into the picture of the Sorek basin in Biblical times that has recently emerged required a new excavation of the site. This would allow us to study the frequent shifts in ethnic and political boundaries, as well as cultural affinities, in this friction zone between Judah and Philistia.

Since nearly three-quarters of the 7-acre mound was already excavated down to bedrock, we have concentrated mainly on the northeastern quarter of the tell, where unexcavated area is still available.

So far, the most ancient remains we have uncovered date to the Iron Age I (c. 1200–1000 B.C.E.), a crucial period in the site’s history, and in Biblical history, for this is when Israel was settling in Canaan.

The evidence from Beth-Shemesh is intriguing—even puzzling. It raises the question, once again, of how to identify Israelite remains in the archaeological record.

In the very first season we found (in Area A) a large structure dating to early Iron Age I that we have called the “Patrician House.” In one particularly long room we uncovered a floor beautifully paved with large river pebbles shining from frequent foot traffic. An internal courtyard contained several fireplaces. The eastern entrance to the courtyard was preserved almost to its full height, about 5 feet. The building had at least one upper story, as indicated by the mass of fallen mudbricks that sealed the ground floor. Was the bedroom on the second floor? We can’t be sure, but some gold jewelry, including an earring, apparently had fallen from above. We found it among the mudbricks of the upper-story walls.

The buildings east of the “Patrician House,” in Area D, were of much poorer quality. A few installations found in them, such as a large grinding stone and a hearth, reflect daily life. In one of the rooms we found an important detail- Near the hearth was a large flat stone that probably served as a base for a wooden column. A row of four similar column bases, contemporaneous with the “Patrician House,” was also found in Area A.

This level was destroyed in a fiery conflagration sometime at the end of the 12th century, in the middle of Iron Age I. We exposed traces of this destruction at every point in our excavation where we reached Iron Age I levels. This destruction debris is probably what Mackenzie called the “Red Burnt Stratum.” Above the ash layer were additional Iron Age I phases, indicating that the site was immediately reoccupied. In the later Iron Age I houses, however, we found a much different kind of roof support from what we found in the early Iron Age I houses directly below. The roof supports in the uppermost Iron Age I level consisted of square monolithic stone columns, which are considered one of the hallmarks of Israelite material culture.

In Iron Age I (the period of the Israelite settlement and the Judges), these monolithic stone columns were common in Israelite settlements along the Judean highlands, the central mountain ridge that runs north and south of Jerusalem. In Iron Age II (c. 1000–586 B.C.E.), the use of these columns spread all over the country.

But such columns are not found in the earliest Iron Age I phase at Beth-Shemesh. The wooden columns found in the early Iron Age I buildings at Beth-Shemesh represent a different architectural tradition, more akin to Canaanite architecture characteristic of the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Age I, known from various sites in the Shephelah, such as Timnah, Tel Halif, Lachish and others.6

Another supposed Israelite ethnic marker is the presence of large storage jars known as collar-rim pithoi, which have a bump around the neck that resembles a collar. Collar-rim jars are rare at the level of the “Patrician House.” Instead, the pottery repertoire from this level shows clear Canaanite affinities.

The strong Canaanite cultural traditions at the site during most of Iron Age I, and the absence of typical Israelite traits, would seem to indicate that at this time Beth-Shemesh was a Canaanite town. Can this conclusion be reconciled with the Biblical accounts identifying the city as Israelite at this time? Or do the Biblical narratives reflect a later political situation that has been retrojected?

One more factor complicates the story even further. Our paleozoologist, Brian Hesse, analyzed over 6,000 animal bone fragments recovered from the Iron I level of the “Patrician House.” Fewer than 1 percent were pig bones; the rest were primarily from sheep and goats. This contrasts with Iron I levels at such Philistine sites as Ashkelon (19 percent pig bones), Tel Miqne/Ekron (18 percent) and Tel Batash/Timnah (8 percent). This in itself is hardly surprising, since we know that the Philistines originated outside the Levant and had different cultural traditions. However, it also contrasts with Late Bronze Age Canaanite sites in the Shephelah and the coastal plain- Lachish (7 percent pig bones), Tel Batash/Timnah (5 percent), Tel Miqne/Ekron (8 percent) and Ashkelon (4 percent). While our results seem quite different from those of Philistine and Canaanite sites, they are quite consistent with the minimal percentage of pig bones at Iron Age I Israelite sites in the Judean highlands.7

So what are we to conclude? Is the relative presence or absence of pig bones, obviously reflecting a different diet, an ethnic marker? Should we conclude that the early Iron Age I level at Beth-Shemesh, with its Canaanite affinities, was an Israelite town because of the absence of pig bones? Does this level reflect the cultural and ethnic interaction between Canaanites and Israelites that must have taken place at border sites like Beth-Shemesh during the period of Judges? If so, who destroyed this town in a fiery conflagration? And who were the new settlers who introduced the pillared house, commonly associated with the Israelites, to Beth-Shemesh? Apparently, they were of a different stock from the people who inhabited the town in the 12th century B.C.E., before its destruction, since they also changed the orientation of the houses and replaced the earthen floors with thick plaster ones. These and other intriguing questions concerning the Iron Age I remains at Beth-Shemesh still await answers in the forthcoming seasons of excavation at the site.

Among the Iron Age II remains in the southern section of our excavations (Area B) was an eighth-century building containing an olive oil press with a large crushing basin and three hole-mouth jars sunk into the pebble floor. A pressing vat and a heavy stone weight were located just outside the building.

Beth-Shemesh was destroyed in the late eighth century B.C.E., during the famous military campaign of the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib. By 721 B.C.E. the Assyrians had put an end to Israel, the northern kingdom. They then turned their sights on Judah and Philistia, to the south- “In the 14th year of King Hezekiah [of Judah], Sennacherib of Assyria came up against all the fortified cities of Judah” (2 Kings 18-13). In a cuneiform account of this military campaign, Sennacherib boasts that he destroyed 46 of Hezekiah’s “strong cities,” driving out over 200,000 people.8 One of our new findings is that Beth-Shemesh was indeed a “strong city” at that time and therefore was worthy of attack by Sennacherib.

The first indication of the city’s importance in Hezekiah’s time (late eighth century B.C.E.) comes from the large number of so-called LMLK (l’melech) handles found at the site (LMLK means “[belonging] to the king”). These words were impressed on the handles of Judahite jars, followed by the name of one of four cities in Judah. Associated with King Hezekiah’s military administration, the jars were apparently mass produced, filled with food supplies and issued to the main strongholds of Judah as part of the preparations for the Assyrian assault.9 So far we have found 13 LMLK handles; previous excavations of the site uncovered 42. We have also found 3 handles stamped with the seal of a royal official; previous excavations uncovered 12. This total is exceeded at only five other sites in Judah- Jerusalem, Lachish, Ramat Rahel, Gibeon and Mizpah/Tell en-Nasbeh. Some of the same officials’ names have been found at both Beth-Shemesh and such important sites as Jerusalem—a strong indication of Beth-Shemesh’s importance in the Judahite military and administrative organization.

If Beth-Shemesh was such an important city during Hezekiah’s reign, how was it fortified? This question especially intrigued us because George Ernest Wright, in his analysis of Grant’s excavation, concluded that Beth-Shemesh “could never have been very important for the defense of the kingdom of Judah.” In his view, after the tenth century B.C.E. Beth-Shemesh was an unfortified village.10

Initially, our own explorations of the site seemed to confirm this. We could find no fortification remains, even in the areas previously excavated. At several points we sunk trial trenches in an effort to find Mackenzie’s “Strong Wall.” Finally, at one place (Area C), we found a massive wall built of four stepped courses of large boulders, which appeared to match Mackenzie’s laconic descriptions and photographs of the “Strong Wall.” Digging down further, we were astonished to come upon a tunnel that ran along the outer face of the wall, barely wide enough for a man to pass through. Suddenly we realized that this was one of Mackenzie’s tunnels, a common method of exploration among British archaeologists in Palestine at the beginning of the century. That we had indeed come upon one of Mackenzie’s tunnels was confirmed when we found an Arabic drinking jar in the tunnel, left behind by one of Mackenzie’s workers. As we peered into the tunnel—a unique relic of pioneering archaeology in the Holy Land—we could not help but admire the daring, adventurous spirit of “founding fathers” of Biblical archaeology like Mackenzie.

We were further surprised, however, to find that behind the “Strong Wall” was an impressive corner of a second wall or of a large fortress, built of large flat stones found on huge boulders. Parts of this fortified corner were preserved to a height of over 6 feet. Its flat upper course indicates that it once supported a massive mudbrick superstructure. The four stepped courses we had earlier come upon were part of a large bastion in front of these fortifications. A most interesting feature in the fortifications was a paved postern (secret passage), which led outside the city through the wall. It was originally roofed with huge stone slabs. (Knowledge of a similar postern apparently enabled the Israelites to capture Canaanite Bethel, according to Judges 1-22–26.)

Mackenzie had dated his “Strong Wall” to the Canaanite period; Wright placed it more specifically in the Middle Bronze Age IIC (17th century B.C.E.). Dating these fortifications is admittedly difficult- With only the foundations preserved, there are no living floors by which to date them. Digging carefully beneath the wall down to bedrock, however, we could date its construction to Iron Age II, probably to the period of the United Monarchy of David and Solomon (tenth century B.C.E.). We established that this was the earliest fortification system at Beth-Shemesh. It was probably built when the political border between Judah and Philistia was established and Beth-Shemesh was fortified and established as a regional administrative center, as suggested by Joshua 21 and 1 Kings 4-9.

In the southern section of our excavation (Area B), we found remains of the Iron Age II (1000–701 B.C.E.) city immediately under the surface. Here we uncovered part of a very large building built of massive walls, three stones in width (4 feet). Walls separated the building’s long halls, which were either paved with rounded riverbank stones or covered with thick plaster. In some cases large flat stones were used as column bases. A thick ashy layer was found everywhere in the house, but no artifactual remains were recovered. Stratigraphically, this building sits immediately on the remains of 11th-century B.C.E. burnt houses. We may conclude, then, that this public building had been constructed by the tenth century B.C.E., probably during the period of the United Monarchy. Thus Beth-Shemesh adds to the evidence of a centralized monarchical administration during the period of David and Solomon.

Indeed, evidence revealed by Grant’s excavation tends to confirm that Beth-Shemesh was thoroughly reorganized during Iron Age II. The haphazard plan of the Iron Age I village was abandoned and the new town carefully planned. Houses were built around the edge of the mound, facing inward upon a street that formed a large semicircle within this area. A few public buildings were built among the private houses; One spacious residence probably housed the city or district governor. A tripartite pillared building served as a storehouse. A large stone-lined silo held grain. All this was revealed in Grant’s excavation.

On a more personal level, we can identify one of the most prominent families in the area for several centuries. Among our finds was a piece of a double-sided game board. On its narrow side the name of its owner is incised- Hanan. Harvard paleographer Frank Cross dates the inscription to the latter part of the tenth century B.C.E. The same name also appears on a 12th-century B.C.E. proto-Canaanite ostracon found at Beth-Shemesh by Grant’s expedition, and “[Be]n Hanan” was found incised on a tenth-century B.C.E. bowl fragment from the neighboring site of Tel Batash/Timnah. Since the Bible lists the place name “Elon Beth-Hanan” immediately after Beth-Shemesh in Solomon’s second district, the excavators of nearby Tel Batash suggested that the family of Hanan must have been of considerable importance in the Sorek valley. Their suggestion is now confirmed by our discovery of the Hanan inscription.

Having established the role of Beth-Shemesh as a fortified administrative center during the United Monarchy, we still faced Mackenzie and Wright’s contentions about the decline of Beth-Shemesh after that period. Admittedly, these contentions seemed curious in light of the strategic position of Beth-Shemesh at the meeting point of the western and northern borders of Judah, facing both the Philistine and the Assyrian menace, and the multitude of royal LMLK handles found at the site. It was therefore with much enthusiasm that we uncovered a previously unknown northern city gate that indicates that the city must have been fortified until its destruction during Sennacherib’s campaign in Judah in 701 B.C.E. This formidable two-chambered gate, which opens onto a plastered city square or plaza (compare 2 Chronicles 32-6), was built at the end of the ninth or beginning of the eighth century B.C.E. directly above the earlier system of fortifications. The new gate clearly confirms Beth-Shemesh’s role as a fortified stronghold on the border of Judah. It is reasonable to assume that the gate was built either by King Amaziah, who may have relied on the gate and the fortifications of which it was a part when he clashed at Beth-Shemesh with King Jehoash of Israel, or by King Uzziah, who expanded into Philistine territory and built cities there (2 Chronicles 26-6).

We now come to the gem of our excavation—the underground water reservoir built at Beth-Shemesh during the period of the United Monarchy. Its discovery can be attributed to volunteers Glenn and Paul White of Massachusetts, a father and son team who learned of the excavation through BAR’s annual survey of volunteer opportunities.

One of the mysteries of the site involved the water supply. As far as we know, Beth-Shemesh lacks a source of living water. So where did the inhabitants get their water, an element so crucial in both the ancient and modern Middle East? The name of a nearby Arab village, ‘Ain Shems, hints at a spring (‘ain means spring in Arabic), but no spring was identified by any of the great 19th-century travelers who investigated the Sorek valley and none is there today.

Both Mackenzie and Grant report finding many bell-shaped cisterns during their excavation of the mound. These homely installations, used to collect rainwater, were dug all over the country until the beginning of the 20th century. We were therefore hardly surprised to find a cistern shaft in the middle of the plaza onto which the northern gate of the city opened. We assumed the cistern was cut in recent times by the fellahin, or Arab peasants, of ‘Ain Shems. But our two devoted volunteers were dissatisfied with this explanation. They insisted on lowering a video camera into the depths of the cistern. Only then did we realize the importance of the find—our most spectacular discovery at Tel Beth-Shemesh! The video photos revealed a mammoth underground water reservoir, with a large central space and four lateral halls branching out to form a huge cross-shaped reservoir.

With the help of a rope ladder, we descended over 20 feet down the narrow shaft of the reservoir. A few intact jugs and hole-mouth jars lying in the silt accumulated on the bottom of the halls indicated that the reservoir had been used mainly during the Iron Age.11

Each of the four branches of the reservoir is 30 feet long, over 20 feet high and 6 to 12 feet wide. (Originally, they were all the same width, but two were later narrowed.) The reservoir was hewn in soft chalk, then plastered up to the ceiling. Initially it was plastered with a nearly 4-inch layer resembling cement. When this cracked, the entire system was covered with a thinner layer of plaster, about ¾ of an inch thick. Signs of periodic repairs to this later layer of plaster can easily be seen.

The capacity of the reservoir is about 7,500 cubic feet. The reservoir was fed with rainwater collected by a network of plastered channels all over the site. A few of these channels were unearthed by us; Mackenzie found others quite near the surface. Surprisingly, one of the channels went through the city gate; usually gate channels are used for drainage, not to bring water into the city.

The running water collected by these channels must have carried much silt, so a routine cleaning of the reservoir bottom would have been essential. Indeed, the 2-foot silt layer on the bottom of the reservoir contained pottery from only the very last phase of use, when normal maintenance of the water system had already ceased.

Even after a preliminary inspection, we suspected that a reservoir of this size probably had another, more convenient entrance. A nearby, slanting dump full of pottery appeared to have been partly thrown into a cavity—a hidden opening? We cleared enough of the dump to realize that it covered a slanting shaft blocked with earth and stones. Further excavation here was too dangerous for our enthusiastic volunteers. We therefore moved to the spot where our calculations indicated (on the basis of the partially exposed shaft) that the head of the shaft and the entrance complex to the underground reservoir should be located. For two seasons we excavated this intricate complex, which retained its secrets until the last moment. Slowly and cautiously, we cleared tons of debris from the depths of an unfamiliar slanting shaft. At last we exposed one of the finest examples of water engineering and management in the kingdom of Judah.

The slanting shaft enclosed a stairway leading down to the water in the reservoir (“The Secret of the Cistern”). Retaining walls reinforced the sides of the shaft. At the east side of the shaft was a large pier, around which the stairway descended. At the bottom of the stairs, one enters the reservoir through a square opening. Inside the opening is a small bench where water drawers could place their jars. Here we found two jars and a globular cooking pot, as if their owners had left them there yesterday.

This construction is one of the most impressive architectural remains from the period of the United Monarchy.

Determining when a water system was built is notoriously difficult because these structures lack living floors and are continuously cleaned of any accumulations. One way to meet the challenge is to identify the latest layer of settlement through which the water system was dug. The water system must have been constructed after this layer. This gives us what archaeologists call a terminus post quem.

A careful investigation of the entrance to our water reservoir revealed that its original walls lie above a heavily burnt Iron I layer. We therefore assume that the complex was built later than this—in the 10th century, the time of the United Monarchy, when Beth-Shemesh was completely reshaped into a fortified administrative center. This conclusion is buttressed by the recent finding at Tel Beersheba of a similar complex that has also been dated to the tenth century B.C.E.

The date when the reservoir went out of use presents yet another problem. In the reservoir we found pottery dating to the seventh century B.C.E., later than the latest pottery found on the mound either by us or by our predecessors. On the basis of the pottery on the mound, we had assumed that the destruction of the city was the work of Sennacherib in 701 B.C.E. So what was seventh-century pottery doing in the reservoir?

Then we found some seventh-century pottery in the earthen fill mixed with stones and broken pottery that had been used to block the entrance shaft to the reservoir from top to bottom.

This suggests a more complicated scenario for the end of Beth-Shemesh. We have no doubt that the fortified city was destroyed during Sennacherib’s campaign in 701 B.C.E., like so many other Judahite sites in the Shephelah. Unlike most of them, however, Beth-Shemesh was not deserted after that. Though probably minor and therefore difficult to detect, human activity continued in some quarters of the site. We assume that the reoccupation concentrated around the water reservoir.

This is evident from the continued use of the reservoir as well as from the seventh-century pottery mixed into the fill in the entrance shaft, which would have been shoveled there from close by. This renewed settlement lasted only a short time, however, and soon failed. Probably Philistines from the neighboring sites of Ekron and Timnah destroyed it after Sennacherib gave them the fertile parts of the Shephelah that were taken from Judah. We conjecture that the Philistines blocked the entrance to Beth-Shemesh’s water reservoir with the fill containing the seventh-century B.C.E. pottery in order to cut off the life source of the town—its water supply—thus assuring the complete abandonment of the site by their bitter enemies, the Judahites.

1. See Duncan Mackenzie, “Excavations at Ain Shems (Beth-Shemesh), 1911,” Annual of the Palestine Exploration Fund 1 (1911), pp. 41–94; “Excavations at Ain Shems (Beth-Shemesh), 1912,” Annual of the Palestine Exploration Fund 2 (1912–1913).

2. Elihu Grant, Ain Shems Excavations (Palestine) 1928–1931, Part I (Haverford- Haverford College, 1931); Ain Shems Excavations (Palestine) 1928–1931, Part II (Haverford- Haverford College, 1932); Rumeileh Being Ain Shems Excavations (Palestine), Part III (Haverford- Haverford College, 1934). See also Beth-Shemesh (Palestine)- Progress of the Haverford Archaeological Expedition (Haverford- Haverford College, 1929).

3. The excavation is being conducted under the auspices of the University of Bar-Ilan and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. We have also received support from the Dr. Irving and Cherna Moskowitz Chair in the Land of Israel Studies, the Dr. Simon Krauthammer Chair in Archaeology at Bar-Ilan University, the Beth-Shemesh municipality and the Jewish National Fund. The project is directed by the authors and by associate director Steve P. Weitzman of Indiana University, Bloomington. Special thanks are offered to all our staff members, BAR volunteers and students from Bar-Ilan University, Ben-Gurion University, Indiana University, and North Bible College in Minnesota.

4. For the identification of the site see Edward Robinson, Biblical Researches in Palestine and the Adjacent Regions, vol. 2 (London- Crocker & Brewster, 1856), pp. 223–224; Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine, vol. 2 (London- Palestine Exploration Fund, 1896), pp. 209–210.

5. For a concise discussion pertaining to the history of the Shephelah during the Biblical period, see Anson F. Rainey, “The Biblical Shephelah of Judah,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR) 251 (1983), pp. 1–22.

6. Amihai Mazar, “Features of Settlement in the Northern Shephelah During MB and LB in the Light of the Excavations at Tel Batash and Gezer,” Eretz-Israel 20 (1989), pp. 62–65 (Hebrew) and additional references there.

7. Brian Hesse and Paula Wapnish, “New Perspectives and Evidence on Ethnicity and the Pig in the Levant” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature/American Schools of Oriental Research [AAR/SBL/ASOR], Philadelphia, November 1995); Hesse, “Pig Lovers and Pig Haters- Patterns of Palestinian Pork Production,” Journal of Ethnobiology 10 (1990), pp. 195–225; Assaf Yasur-Landau and Shlomo Bunimovitz, “The Philistine Kitchen—Foodways as Ethnic Demarcators,” in Eighteenth Archaeological Conference in Israel, Abstracts (Jerusalem- Israel Exploration Society/Israel Antiquities Authority, 1992); Ann Killebrew, “Functional Analysis of Thirteenth and Twelfth Century B.C.E. Cooking Pots” (paper presented at the annual meeting of AAR/SBL/ASOR, San Francisco, November 1992).

8. James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, rev. ed. (Princeton- Princeton University Press, 1955), p. 287.

9. Bibliography concerning the issue of LMLK jars is extensive. See most recently Andrew G. Vaughn, “The Chronicler’s Account of Hezekiah- The Relationship of Historical Data to a Theological Interpretation of 2 Chronicles 29–32” (Ph.D. diss., Princeton Theological Seminary, 1996), chap. 4. See also Nadav Na’aman, “Sennacherib’s Campaign to Judah and the Date of the LMLK Stamps,” Vetus Testamentum 29 (1979), pp. 61–86; Na’aman, “Hezekiah’s Fortified Cities and the LMLK Stamps,” BASOR 261 (1986), pp. 5–21, and reference there.

10. Grant and George Ernest Wright, Ain Shems Excavations (Palestine), Part IV (Haverford- Haverford College, 1938), p. 26; Wright, “Beth-Shemesh” in Michael Avi-Yonah, ed., Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (English edition; London- Oxford University Press, 1976), vol. 1, p. 252.

11. The first inspections of the water reservoir were conducted with the help of a group of researchers from the Israel Cave Research Center headed by Tsvi Tsuk. They also prepared the reservoir’s plan, which was drawn by Judith Dekel (Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University). We thank them all for their help.