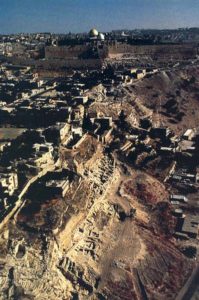

For eight seasons Yigal Shiloh directed excavations in Jerusalem—the heart of the Biblical world. And not simply any place in Jerusalem. He dug in the oldest inhabited part of the ancient site, the section known as the City of David, the area that comprised the city when King David captured it from the Jebusites and made it the capital of the United Kingdom of Israel.

For eight seasons Yigal Shiloh directed excavations in Jerusalem—the heart of the Biblical world. And not simply any place in Jerusalem. He dug in the oldest inhabited part of the ancient site, the section known as the City of David, the area that comprised the city when King David captured it from the Jebusites and made it the capital of the United Kingdom of Israel.

The importance of the site was matched only by the difficulties in excavating the precipitously steep slope that had been picked over by a host of predecessors. But Shiloh confounded the skeptics and uncovered spectacularly informative remains that brought him world-wide fame and adulation.

Then, in 1985 he was diagnosed as having stomach cancer. Two years later, on November 14, 1987, he died, thus ending a meteoric career whose short but brilliant light will be remembered as long as the history of Jerusalem is treasured.

The following two-part interview (Part II will appear in the May-June BAR “BAR Interview- Yigal Shiloh—Last Thoughts, Part II,” BAR 14-03) took place on June 30, 1987, at Yigal Shiloh’s home in Durham, North Carolina. Shiloh was teaching on a sabbatical at Duke University and also was being treated for stomach cancer by specialists from the Duke University Hospital.

Two years earlier, Shiloh had had more than half his stomach removed, but the operation did not get all the cancer; it reoccurred and was eating away at his vital organs. But his spirit refused to give up; there was one more procedure that might work. The procedure is described in the first part of this interview.

Unfortunately, Shiloh never regained enough strength to allow this procedure to be used. Finally, in October, he asked to return to Jerusalem. Two weeks after he returned, he was awarded the prestigious Jerusalem Prize in Archaeology. The presentation was made at his bedside by Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek. A week later, Yigal Shiloh died.—Ed.

June 30, 1987, Durham, North Carolina.

Hershel Shanks- Yigal, we’ve talked several times about the possibility of recording an interview. You said when you got a little stronger you would give me a call and we would do it. And yesterday you called me in Washington. I was, of course, delighted to hear you’re feeling stronger, and here we are.

Yigal Shiloh- It’s been a long fight, and I’m building up now to the next stage.

HS- What is that next stage? You told me the procedure and it sounds very hopeful. What is it?

YS- The main way to fight tumors [cancer] today is with chemotherapy. But the different agents of chemotherapy also destroy your own body. The stronger the chemical, the better the chance that it will take care of the tumors. But it will also destroy your own body more.

So now what they will do is to harvest my own bone marrow in a separate operation, not so complicated a one. Then they put it aside, freeze it. Then I go into chemotherapy, but very strong chemotherapy, ten times stronger than usual. As I said, hopefully, I have a good chance. But this very heavy dose of chemotherapy will completely break down my immune system—everything. But I can take this risk because they will have my frozen bone marrow. The next phase, after the chemotherapy, is to give me back my own bone marrow. They transplant my own bone marrow into myself, which is an easy process because it’s not rejected since it’s myself. The bone marrow that was in the body is affected by the chemotherapy, but the bone marrow that was frozen comes in again and helps to rebuild the immune system of my body. It is a process of a few weeks. Not a lot of danger. It is done in isolation, complete isolation because I will be completely without immunity to infection until it is built up again.

So now I have to regain my strength and re-build my white cells from the last chemotherapy. Once my body is normal and functioning with its usual blood counts again, then they will harvest my bone marrow, put it aside—it can wait for years—and then I will wait for an available isolation room and the heavy chemotherapy.

HS- You’ve been a bright light to all of us for your courage. You know that? The way you’ve reacted, with such strength, you’ve said, “I’m going to live my life and do what I need to do.”

YS- I don’t have any other choice.

HS- Well, that’s part of your courage. Many people would give up more easily.

YS- I know the feeling of giving up in this situation. But even when you’re close to giving up, you get to a point where you ask yourself “What next?” And what next is not giving up. As long as there is a solution, it’s really a tough fight, but it’s not a lost fight. Statistically, some say there’s nothing here. But whatever I can do, I am doing. I don’t see why I shouldn’t fight all the way. I’m almost 50. Next week, I will be 50 years old. My life was never easy. But I have always done things.

Now it’s really frustrating—frustrating because it’s not in my hands or in my head. I cannot control things. I cannot decide how much I want to go on or how much I want to do. I’d like to do everything I can. And who knows what.

HS- How long ago were you diagnosed as having cancer?

YS- In December 1985. A little more than a year and a half ago. I had hoped that the first operation would be enough. Unfortunately, it was not. So we are going on.

HS- What did they do in the first operation?

YS- They took out two-thirds of my stomach. We hoped that this, with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, would take care of things. But it was not enough.

HS- Your greatest accomplishment and your best known archaeological effort has been a major excavation of the oldest inhabited part of Jerusalem, called the City of David (Ir David). In December of 1985 when you discovered that you had this tumor, had you finished your excavation?

YS- We finished the excavation long before December 1985. I’m sometimes shocked by the fact that nobody believed me when I said we were finished. I mean they would be thinking, “Are you really going to stop excavating such a nice site? With so much potential?” I won’t mention names here, but some of my colleagues have gone on this way, year after year. But I said “Yes, I’m stopping. Seven or eight years of excavations are enough for a first stage.” We planned to excavate for five years. We went on for two or three years more because it had to be done to answer some questions. Now we finished this chapter of research on the City of David.

It’s unfortunate that I’m not able to give 100 percent of my time to the work as I would like to do but we are clearly moving forward. And when we come to the stage that we have digested everything we have already excavated, then I will allow myself to excavate again in Jerusalem—or in another site. We all know that in eight weeks in a summer, we archaeologists uncover enough material to work on for the whole year.

And it is very important that we “clear the house” each year. I mean the technical work—not analysis, not publication, but technical work, stratigraphy, pottery drawing, photographing, basic analysis and so on. If you do these things, then you will be in control. Otherwise, not.

Originally, we did not put our material into a computer. I hesitated to do so at the beginning. I did not know exactly what to ask, what answers we were trying to get. But now I do. So we put everything into the computer, and now I’m just delighted. I can go into the files that I have here and look at a single locus out of 20,000 loci that we have at the site—and get the answers out easily. But it is very much ant’s work. It’s technical. But we have to have all these details to come to our conclusions.

I just saw a very interesting quotation from an interview you did [in BAR] with Avraham Biran (“BAR Interview- Avraham Biran—Twenty Years of Digging at Tel Dan,” BAR 13-04), where he says that the younger generation of Israeli archaeologists deal too much in details; they don’t draw general conclusions, but men like Albright and Breasted, he says, could see the overall picture.

I can agree and disagree with Biran at the same time. Biran is older than I by almost 30 years. I admire him as a person and his archaeological outlook and his life, and so on. I will not argue with him, because there is this gap between the generations. But what is this archaeology that deals too much in details that he criticizes. This is exactly what archaeology is today. It’s a science. And science has to deal with details. No single detail is more important than any other. There is no such thing as too many details. But he’s completely correct—and that’s why we have to learn from him and from our many other teachers—we don’t draw general conclusions. The general picture is a very important one.

I dwell on the subject because these details—once you put them all together—every piece, level, stratum, coin, definition, etc., once you put them together, in a computer system—if not now, in the future for sure—you will get some beautiful pictures. You will be able to visualize everything very quickly.

HS- Now that you’ve completed the first phase of your Jerusalem dig, what is the overall significance? Is it just the finds? Some of them are obviously extraordinary, but what do we know about ancient Jerusalem, about ancient history in general, that we didn’t know before?

YS- Jerusalem is a unique site not only in Israel, but in the entire ancient Near East. It’s unique because we have three, four and sometimes five archaeological expeditions going on at the same time. It’s also a city with a very special history, a very complicated history.

HS- If you had to describe in a few sentences what your excavation has added to this complex story…

YS- I don’t like your saying “your excavation.” My excavation becomes more significant as part of the other excavations going on in Jerusalem. I would like to say “our excavation” because the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University has three main Jerusalem projects- [Professor Benjamin] Mazar’s excavation at the southern wall of the Temple Mount, [Professor Nahman] Avigad’s excavation in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City and my excavation in the City of David. As a young archaeologist at the Institute, I got the real tough area. They sent me down to the southeastern hill. That was left for last. They were not sure that anything could be found.

When we went down there to dig, we didn’t just go to excavate. I’m surprised sometimes to find archaeologists, when you ask them “What are you going to do?”, they say “I want to open five areas and two sections.” When you are going to attack a site you must ask, “What do I want to find out here? What was the condition of the site before? What am I looking for?” And if I decide what I’m looking for, what system am I going to be using?

Kathleen Kenyon’s principle error when she excavated in Jerusalem [1961–1967]—and some of her errors were really major ones, unfortunately—occurred because she didn’t think that way. She dealt with Jericho [1952–1958], with Jerusalem, and maybe even Samaria in the 1930s in the same way. The City of David is far more complicated than the others. It has so many problems. You can’t deal with it like I did in Megiddo, where I opened one area in the north and one in the south, using the same method in each area. No, in the City of David we used different methods, different systems, for different areas. In one area I had to use small brushes all the time, and clean, and go very slowly from the Early Bronze Age and the Chalcolithic period [4th millennium B.C.], and try to collect every item. In another area, like Area A in the south, I had to spend more than two weeks with a bulldozer just to push away dumps of previous excavations in the Mandate period. And then I had to make a special survey to look for the dumps of Raymond Weill, who excavated there in 1913–14 and 1923–24. After making sure I located them correctly, it took another two weeks just to clear them with a bulldozer.

Now you can tell me to do it in slow motion for eight years [without a bulldozer], but the money is public. You can’t do it so slowly. So I think we found the right way to do it. We used the right method and the right tools and I believe we got a beautiful picture of the archaeology of the City of David.

You ask what did you find there. I always smile at this question. I say, I don’t know what you want. First of all, go to the site. We left behind a beautiful archaeological garden. I go there sometimes like Nehemiah when he came by night to inspect the walls of Jerusalem. I just walk between the tourists going up and down Warren’s Shaft to hear what they are saying. I enjoy that. We spent some very tough, dangerous years there. There were some nights I couldn’t sleep, literally. I would pray to God that the season would finish and we would be out of that tunnel without an accident. But I took the risk. When I think about it today, I believe it was too much of a risk, but I took the risk because I knew what we were looking for.

But if you had asked me at the beginning how delighted I would be at the end, what interesting results we would get not only by reopening Warren’s Shaft, but also the kind of scientific information, the hydrogeological research that we have done, I would not have believed it. We are still working on this project to understand the water systems. A friend of mine from the department of geography and earth studies is now checking the outflow of the Gihon Spring, day by day, hour by hour. He has some beautiful results that will be coming out. We will know the connection, for example, between the rainfall in Jerusalem and the outflow of the Gihon Spring. People ask why was Jerusalem chosen as a site for a city. Maybe one of the reasons was because they knew about the water supply, the perennial water from the Gihon Spring, which is the best in all the area. This is only one point. There is much more. Second, we’ve got a museum now in a special corner of the City of David for all finds. Third, the City of David is part of a mosaic of culture—Canaanite, Israelite, Christian, Roman.

When we came to attack the mound, I took out a map that showed every building in the City of David, and I put arrows on it—blue and red. The red arrows were what I wanted to do. The blue arrows were what I could do. There was a big difference, unfortunately, because of the houses and land ownerships and so on.

But I had to start somewhere. My main idea was to connect the City of David excavation—in which I would have, I hoped, Canaanite and Israelite levels—with the Temple Mount excavation to the north. At the same time I had to think about other things—the ancient water system; the fortification lines; how can I get to the earliest phases of the city without staying too long in the upper levels? I considered how to attack one problem after another.

HS- Do you remember, Yigal, in one of her books, Kathleen Kenyon described the difficulties of digging in the City of David and what she had uncovered and found. She concluded with a statement something like this- That if anybody else wants to go back to this pile of rocks, let them, and I wish them good luck. She implied that she didn’t think there was anything more to be found. Do you remember that?

YS- Not only do I remember it, I underlined it. I underlined two things in her book in this connection. One was that she said that if you want to excavate here any more you will have to use technical devices. The other thing, that she mentioned three or four times, is that there is no way she could see any reason to go back there.

Here again we come to one of the basic questions in the science of archaeology today—how to excavate. Kenyon was a devoted believer—we learned from her—in [long], narrow sections. We too had an area—Area E2, which we called the Kenyon section—where we used a [long], narrow section. It was so difficult to excavate because it was only three meters wide and twenty meters long. I wanted to be sure that there was no other line of fortification below it on the slope. So I went down in a very narrow section to the bedrock on the slope. This was so typical of how Kenyon dug that we called it our Kenyon Section. There is no question that this is one very important way to excavate. But it is not the only way. That’s the point. Kenyon thought once she took an area and, like a checkerboard, put down four small squares, perforating the area, that she had finished her work, that she got all of the material out of the area.

This is wrong in a regular mound. It is 100 percent wrong in the City of David and in Jerusalem.

In a salvage excavation last summer in Jerusalem, which was not done using the best archaeological techniques because it was a salvage operation, some very important finds contradicting Kenyon’s conclusions nevertheless came out, despite the fact that she had dug so very meticulously wherever she worked.

What we have learned in the last 20 years, between American and Israeli methodology especially, incorporating both in a common project, is that we must use more than one method. You start with a narrow section to scout the area, to learn what you will be looking for. Once you get an idea of the stratigraphy, you have to widen the area. But you widen it under control. Do you want to widen it in the Byzantine period, in the Early Bronze period, in the Iron Age? It’s up to you.

But you can never get enough material. In the City of David we could work for five years in one area alone, and still only be in the Iron Age.

One year we were working in an Iron Age area and we found, as Kenyon would have said, that it was built no earlier than the eighth century B.C., Hezekiah’s time.

The next year we started a new square, one meter to the north of this area. We went down—and boom—we came to the Solomonic period [10th century B.C.]. The next year, in another area farther north (Area E), we got Middle Bronze and Early Bronze material.

What happened? This is a mountainous area. Here we were digging in a big depression in an area that Hezekiah had rebuilt in the eighth century, but here [because of the depression], he didn’t clear everything down to the bedrock; he just leveled it. So here we hit an earlier history of the city—one area right next to the other. That’s why it’s so important to work with a larger area, to combine sections. Kenyon didn’t do that and that was a great mistake.

We can’t imagine the grandeur of Jerusalem in the Iron Age. Even I can’t imagine it. I’ve excavated royal centers like Megiddo, like Hazor, and I’ve worked on monumental art. These other sites covered about 60 to 100 dunams [15 to 25 acres], generally speaking. And these were big sites. Jerusalem had 60 dunams [15 acres] in David’s time. That was the area of the Canaanite city. But when David added the Temple Mount and all the adjacent area, we jump to 150 dunams [37 acres] in the tenth century. By the eighth century we are talking about a site of 600 dunams [150 acres]. I try to stress this in my lectures, but I don’t know how to do it. I mean, this is six times bigger than any other site in Palestine. And that is not the end of it. Because, we now know from the work of Gaby Barkay and others, the northern area was settled too, although it was not fortified. So you have to add a lot of suburbia around it. We are talking about a phenomenon that never existed before in Palestine. What is the next biggest site in Judea? Lachish with 75 to 80 dunams [20 acres], a little more than 10 percent the size of Jerusalem.

That’s why it’s so important, if you find, for example, a capital, as we have. This gives you an idea about what the city was really like. But just a sample. This is why we must look at the details. We have, as it were, only a button, and from that we must reconstruct the robe—and what a beautiful robe it was. Take this single [lower part of a palmette] capital that was found. It’s very hard stone, mizzi. Almost all other capitals were done in nari stone, which is very soft stone. But in Jerusalem, they used hard stone, just like in Greece. The curves on this single Jerusalem sample are not angular but round and beautiful. Things like this show you how fine a piece it is.

Then we found other small pieces that give you an idea of what Jerusalem was like at its height in the Iron Age. That’s why meticulous work like we are doing, collecting every small piece, is so important.

Take the charred wood we found. So okay, it’s a nice piece of furniture. But let’s go one step further. That’s what I try to teach my students to do. We went to the school of applied sciences at the [Hebrew] University and asked them to identify the tree from which the furniture was made. And if they can identify the tree, can they tell us where it came from? So we found out that some pieces of the wood were not local, but imported from Turkey and Syria—decorated wood from southern Turkey and northern Syria. We know about the big cities there. This puts the whole thing in a kind of perspective. It’s so important because the opposite is often argued, that Jerusalem in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. was an isolated site—politically and culturally—up in the mountains. That’s why every bit of evidence is so important, like this charred wood or a small South Arabian inscription we found which proves connections with certain Arabian elements, it gives us an idea of how the local culture was mixed together with other elements.

Pottery typology today is advancing very well, especially in the Iron Age. We don’t talk about pieces of sherds any more; now we compare complexes of pottery. If you compare different Iron Age sites, going down from Jerusalem to Lachish to Miqne, Batash, Ashdod, Ashkelon, you find that three regions emerge. One is the coastal area—Ashdod, Ashkelon and so on. Second is the Shephelah, the low hills that form a kind of border between Judea and the outer world; there we have Miqne and Batash. The third area is Judea itself in the hills—Tell Beit Mirsim, Lachish, Jerusalem, Ramat Rachel and so on. When you compare the material cultures of these three areas, you find a striking difference. Look at the pottery. In Jerusalem and Lachish—Judea—it’s almost purely local. More than 80 percent of the pottery is local Judahite pottery. There is a little bit of imported ware, but very little. Then you move to the Shephelah, down to Miqne and Batash. There you find about 30 percent or even more of the pottery is imported from the coast and less than 70 percent is local. Then you move to the coast and the percentage of local pottery falls still more. Then go south. In Beer-Sheva, for example, you have a new element—the Edomite pottery. About 30 percent of the pottery at Tel Malhata is Edomite. This shows that today, from a technical point of view, we can define different cultures. In the Judahite mountain sites we have a highland culture. When you go down you begin to have more connections with others.

HS- Something that is puzzling to me is the relative paucity of material from the early tenth century, from the Davidic and Solomonic Monarchy, the United Kingdom. You tell me that there was such great glory and yet, isn’t it true that statistically much, much more pottery has been found from the late eighth century than from the early tenth century?

YS- In each area we uncover an abundant quantity of pottery and finds from the latest level of settlement in that area whether it’s Middle Bronze, eighth century, seventh century …

HS- What about the tenth century?

YS- Just a moment. In Jerusalem we are dealing with a terrace system. Now the last king of Judah to maintain this terrace system—to build it and repair it—was Hezekiah in the late eighth century B.C. In certain areas we excavated the last three levels of Jerusalem ending with Hezekiah. Everything earlier was gone. Hezekiah built on bedrock. He cleared it to bedrock. In other areas, where we moved to the side, we have a second kind of area that was not destroyed by the builders of the last level. There we started to get an abundant quantity of other finds.

HS- Did you excavate an area where you got abundant early 10th-century finds?

YS- Yes, we have an area with 10th-century finds. But what happens—and I’ve spoken about this again and again—the builders of each period went down to bedrock. You have to be lucky. In the City of David the eastern slope was neglected after the First Temple period [ending in 586 B.C.]. When Nehemiah returned to visit the site in his famous night walk, he could hardly walk there because all the houses had been destroyed. These are the houses we excavated. He discovered them 150 years after they were destroyed. We, 2500 years later.

HS- When Nehemiah built his wall, he built it higher up on the slope.

YS- Yes, he built everything on top of the hill and neglected the whole eastern slope. This was fortunate for us. So in this area the first level we came to was a little from the Persian period [sixth to fourth century B.C.], but mainly from the late Iron Age.

Now let’s move to the next phase. In the area I just described they built their houses on bedrock. But then for some reason, they decided to build the city wall at some five, six, or seven meters farther east, farther down the slope. In the area between the houses on bedrock and the city wall was a depression. When we excavated in this depression, we found Early Bronze material, Middle Bronze material, Late Bronze material, even Chalcolithic. Do you understand? This proves again and again what I said about the defects in Kathleen Kenyon’s system of working. You could work five years in one area. For example, in the southern part of Area E, we worked for five years. For five years, we found material only from the eighth century, the seventh century. We were very happy with this, no doubt. But once we moved farther north, just three meters, there was a depression. We looked down and instead of bedrock we found Middle Bronze and Early Bronze material. This ended up being the area where I excavated the first house from the Early Bronze Age, below the Iron Age city wall. Now I have another such house, but only two of them.

Do you think Early Bronze Jerusalem was comprised of only two houses? No, of course not! But it’s again a sample, a very nice sample that allows us to understand Jerusalem of the Early Bronze period.

HS- I’d like to ask you about the stepped-stone structure. This was a huge, monumental structure. Is it the largest structure in Iron Age Palestine?

YS- In dimension, yes. The only other structure I know of that is so large is the platform for the palaces at Lachish. Another large structure was the huge earthen wall that existed in Samaria. Not everyone knows about it, but it was there.

HS- You’ve speculated as to what this huge Iron Age stepped-stone structure was.

YS- I didn’t speculate. I don’t speculate.

HS- You suggested that it was used to support some other structure.

YS- It is a supportive wall, a revetment wall that held up the base of something that was built on top of it. Nothing more.

HS- Why would they go to all this trouble? They apparently built something on top of a hill that stuck out over the side that needed this enormous support. Why would they do that? Why not just move farther over on top of the hill? Then they wouldn’t need this huge structure as a support.

YS- There was no more space on top of the hill. That’s exactly the point. The Iron Age builders were not the first to do this, nor were they the last. You must put yourself in their shoes. You’re looking at it from outside, from a modern viewpoint. Why should they bother, why should they do this? I learned in archaeology a long time ago—and this helps me greatly—to put myself in their shoes, to enter their way of thinking. Now what happened here? The Early Bronze period was delightful in Jerusalem. The first Early Bronze people settled in the nicest area, very close to the spring. The next families moved higher and higher up the hill. Then they had a problem. In the Middle Bronze Age, and the Late Bronze Age, when they wanted to build a fortress, something like they had at Lachish, they had to build up huge terrace walls to form a base and a flat surface. We found these terrace walls at the base of the stepped-stone structure. Then they filled the space between the terrace walls to support the structure on top. From the top to the supporting walls at the lowest point is over 25 feet, filled with stones. This system was used all over this area, even though you can’t find it all now. In an article in Levant, Hank Franken talks about why Kenyon couldn’t see this phenomenon. In the end, he agrees with me, he can see it.

HS- So the lower part of the stepped-stone structure is Late Bronze?

YS- The lower part is Late Bronze.

HS- Canaanite?

YS- Canaanite. These terraces provided a large area for construction. Kenyon said that these were terraces of houses. But she was wrong. They were technically just revetment walls to provide more level space in this area for construction.

Now, be careful. A second phase is Israelite, completely Israelite. The Canaanite buildings on the slope here were completely destroyed. Huge elements of the revetment wall (terraces) still exist from what was the base of the acropolis of the Canaanite period. But then in the Israelite period, you have a new system, a new acropolis. This was just one point where we found it, but they did it all over. Israelites patched up the Canaanite system, they filled in the gaps. Some scholars suggest that this is what the Bible refers to when it says that David and Solomon repaired the Millo [1 Kings 11-21; 1 Chronicles 11-8]. Maybe. I am not sure.

So first you have the Canaanite filled terraces from the Late Bronze Age. Then you have the stepped-stone structure from the Israelite period. Then something else happened in Jerusalem. They needed still more space. They built all over this area. The Israelites decided to build houses even lower down from the acropolis and even into the sides of the stepped-stone structure. Then it was all destroyed by the Babylonians [in 586 B.C.]. Then in the Hellenistic period, a huge, smooth revetment—a glacis—was placed over and covered the whole area.

Now the Hellenistic period was the last in which a revetment was built here. Actually, the last one wasn’t in the Hellenistic period; the last one was our expedition.

HS- [Laughter.]

YS- Don’t laugh. We did it. Why? We built a revetment to support the buildings on top of the hill. We did the same thing as the ancients, purposely. We used cement rather than stone. You can see it today. This will be Shiloh’s monument. It will be different from Shlomo’s [Solomon’s] monument.

But, you see, you must see with the eyes of an architect in this area, you must consider the needs, and then try to understand why they would go to such misery, such great effort to meet their needs. The more powerful the kingdom, the more construction that will go on. Nothing can stop it. That’s how you can judge the period.

That’s what I teach my students, but with them I go in the other direction. With you, I come out with the conclusions. With them, I say look through this beautiful window on Jerusalem. What can you conclude from what you see?

HS- As we mentioned earlier, when Kathleen Kenyon finished her excavation here, she in effect said good luck to anybody who follows her, but they will not find much. What do you say? Is there more to be found in Jerusalem?

YS- Yes. But I believe the eastern slope of the City of David is finished.

HS- There’s nothing more in the eastern slope?

YS- Well, in 20 years if a new system is developed, there may be more even here. But if you ask me what about now, I say give me some money, and I will go to some places on the top of the hill. I believe that with meticulous work going from one area to the other, renting some sites, excavating them, and then giving them back, there is much to be found. Here we could find some very interesting things about the inside of the city, not just the edges of the city, as we have been doing. There would be nothing surprising from the later part of the Israelite period—the eighth, seventh century B.C. We already have plenty of information from our excavation relating to this period. But for earlier periods we would surely get something on the top of the mound. We would then be in the heart of the city.

HS- Why wouldn’t these earlier periods have been destroyed by later periods up there as well?

YS- It would be destroyed by later periods. But I believe in my system of excavating one square next to the other, I would have a lot of Byzantine squares and Roman squares, but in a very meticulous way, we can find some area with earlier material—just as [Benjamin] Mazar found in his excavation south of the Temple Mount.

In Part II of this interview which will appear in the May-June BAR (“BAR Interview- Yigal Shiloh—Last Thoughts, Part II,” BAR 14-03), Yigal Shiloh describes his confrontations with ultra-Orthodox extremists who claimed that the City of David archaeologists were defiling a cemetery and tried to close down the dig. He also airs his views on the term “Biblical archaeology,” talks in detail about the Israelite four-room house, and shares reminiscences about Israel’s great archaeologists of the generation before him—Benjamin Mazar, Yigael Yadin and Yohanan Aharoni.