Winter is sometimes the best time to dig in Israel’s Negev desert—and sometimes the worst. In summer the heat can be stifling; while in winter, cold windy days at times prevent any outdoor work. It was the winter of 1979 when I began to excavate Tel Ira, a site in the eastern Negev.a

Winter is sometimes the best time to dig in Israel’s Negev desert—and sometimes the worst. In summer the heat can be stifling; while in winter, cold windy days at times prevent any outdoor work. It was the winter of 1979 when I began to excavate Tel Ira, a site in the eastern Negev.a

As BAR readers know, modern archaeologists never excavate a site in isolation. Any site must be understood in the context of the entire area or region of which it is a part.

So naturally we conducted a detailed survey of the region around Tel Ira. Not surprisingly, we discovered literally scores of small archaeological sites that had previously been unknown.

One morning in January we were riding in our Jeep about five miles east of Tel Ira, slowly climbing the deeply fissured side of a hill above the Malhata Valley, looking for new sites. Our experienced eyes easily detected archaeological remains on the highest part of the flat-topped hill. We quickly drove the remaining way up the hill and jumped out of the Jeep.

Scattered about the site were large quantities of pottery sherds, all from the end of the Iron Age period, the ubiquitous archaeological indication of occupation in the Israelite period.

But as we collected the sherds, we also found some rarer objects—fragments of clay figurines and reliefs. I had been an archaeologist for 22 years. I had excavated more than 20 sites and surveyed vast areas. But never before had I seen a site with figurines and reliefs strewn about the surface.

I knew that obviously the site should be excavated, not simply surveyed on the surface. The funds needed for excavation were, fortunately, not large, but, in the restricted world of archaeological financing, five years would pass before we were able to obtain funding even for a small-budget excavation.

In 1984 we began the excavation of the site—named Horvat Qitmit, the ruins of Qitmit.b With help from the army, our small team from Tel Aviv University’s Institute of Archaeologyc has now completed 13 short periods of excavation at the site.

The excavation is not yet complete, however, and the research and analysis of the finds has barely begun, but enough is already known—and the material is so exciting—to justify what must be regarded as a preliminary report to BAR readers.

We now know that we are uncovering the first Edomite shrine ever excavated. Moreover, this Edomite shrine is located not in Edom but in ancient Judah, a fact, as we shall see, that has very considerable geopolitical significance,

Until barely 50 years ago, our sole information about the Edomites came from the Bible. We knew of the land of Edom east of the Jordan and south of the land of Ammon and Moab. We also knew that the Edomites were the hated enemy of the Israelites.

In the Biblical genealogies, Jacob’s twin brother Esau is the ancestral founder of the Edomites (Genesis 36). Jacob and Esau struggled even in the womb (Genesis 25-22). When Rebecca, their mother, pregnant with twins, inquired of the Lord, she was told-

“Two nations are in your womb,

Two separate peoples shall issue from your body;

One people shall be mightier than the other,

And the older shall serve the younger.”

Genesis 25-23

Esau was the firstborn, red and hairy. He became a hunter who sold his birthright to Jacob for a mess of pottage. By trickery, Jacob also obtained his dying father’s blessing, making Jacob master over Esau in fulfillment of the prophecy given Rebecca. When Esau learned what had happened, he was furious and sought to kill Jacob. Warned by his mother, Jacob fled to the land of her brother Laban.

When Jacob returned more than 20 years later, the two brothers were reconciled in tearful embrace. But they never really got along together, despite—or perhaps because of—their fraternal relationship.

Unlike Jacob, Esau took wives from among the Canaanite women. Esau then took his family to settle in another country.

“Esau took his wives, his sons and daughters, and all the members of his household, his cattle and all his livestock, and all the property that he had acquired in the land of Canaan, and went to another land because of his brother Jacob. For their possessions were too many for them to dwell together, and the land where they sojourned could not support them because of their livestock. So Esau settled in the hill country of Seir—Esau being Edom” (Genesis 36-6–8).

The powerful animosity between the Israelites and the Edomites is reflected in the divine admonition in Deuteronomy 23-7- “You shall not abhor an Edomite for he is your kinsman.” The abhorrence made the divine command necessary.

From the viewpoint of the Biblical historian, the source of much of Israel’s antagonism toward Edom could lay in the Edomites’ refusal to allow the Israelites to pass through Edom on their way to the Promised Land following the Exodus from Egypt, or more probably, the antagonistic relationship between the two neighbors may have had an influence on the telling of the Biblical story.

After leaving Kadesh-Barnea (which bordered on the land of Edom), the Israelites sent a message to the king of Edom-

“Thus says your brother Israel- ‘You know all the hardships that have befallen us; that our ancestors went down to Egypt, that we dwelt in Egypt a long time and that the Egyptians dealt harshly with us and our ancestors. We cried to the Lord and He heard our plea, and He sent a messenger who freed us from Egypt. Now we are in Kadesh, the town on the border of your territory. Allow us then to cross your country. We will not pass through fields or vineyards, and we will not drink water from wells. We will follow the king’s highway, turning off neither to the right nor to the left until we have crossed your territory.’

“But Edom answered him, ‘You shall not pass through us, else we will go out against you with the sword.’

“‘We will keep to the beaten track’ the Israelites said to them, ‘and if we let our cattle drink your water, we will pay for it. We ask only for passage on foot—it is but a small matter.’

“But they replied, ‘You shall not pass through!’

“And Edom went out against them in heavy force, strongly armed. So Edom would not let Israel cross their territory, and Israel turned away from them” (Numbers 20-14–21; see also Judges 11-17).

So the Israelites were forced to take another, more circuitous route.

According to Joshua 24-4, the Lord gave Esau—that is the Edomites—the hill country of Seir- “I gave Esau the hill country of Seir as his possession, while Jacob and his children went down to Egypt” (Joshua 24-4).

The land of Edom extended from the Wadid el-Hasa (Nahal Zered in the Bible, which runs into the Dead Sea) on the north to the mountain slopes north of Eilat on the south. Edom’s western border was the Arabah, the rift that extends south from the Dead Sea to the Red Sea. On the east, Edom’s border was the desert. The country sits on a high plateau, 3,500 feet above sea level. The adjacent Dead Sea is nearly 1,300 feet below sea level. The climate of the area is desert-like, although it has some water sources and certain areas are suitable for dry (that is, unirrigated) farming.

Israel and Edom fought with each other throughout the period of the Israelite kingdom. Saul, the first king of Israel, we are told, waged war against Edom (1 Samuel 14-47). His successor, King David, defeated the Edomites, and they consequently became his vassals (2 Samuel 8-13–14).

Israel apparently ruled Edom throughout David’s reign, as well as during Solomon’s reign. As late as the reign of King Jehoshaphat (870–846 B.C.), we are told that “there was no king in Edom” (1 Kings 22-47).

In the reign of Jehoshaphat’s son Joram (sometimes written Jehoram), the Edomites successfully rebelled and set up a king of their own (2 Kings 8-20)- “Thus Edom fell away from Judah to this day” (2 Kings 8-22).

In the reign of Amaziah (798–769 B.C.), Edom again came under Judah’s control; Amaziah, we are told, “defeated 10,000 Edomites in the Valley of Salt, and he captured Sela in battle” (2 Kings 14-7; see also 2 Chronicles 25-11–12). Amaziah’s son Azariah (or Uzziah) apparently completed the reconquest of Edom, for we are told that he restored Eilat to Judah and built it up (2 Kings 14-22).

Unwilling to accept a situation in which it was cut off from the maritime traffic of the Red Sea (as a result of the loss of Eilat), Edom managed to throw off the Judahite yoke during the reign of King Ahaz, at least to the extent that Edomites again settled Eilat—again the Bible adds, “to this day” (2 Kings 16-6).

For the next 150 years or so—at least until the Babylonian destruction of Judah in 586 B.C.—Edom flourished economically and enjoyed the high point of its political power. At the same time, the northern kingdom of Israel was conquered and destroyed by the Assyrians; and the southern kingdom of Judah was under increasing pressure, first from the Assyrians and then from the Babylonians. Edom, on the other hand, by means of shrewd diplomacy and cautious political policies managed to avoid getting involved in the aggressive campaigns of the superpowers and, despite the conquests of Assyrians and Babylonians in the region of Edom, managed to preserve is geographical integrity.

The implacable feelings of enmity and hatred between Israel and Edom—the result of this long history of strife and warfare—is clearly reflected in the prophecies of Israel’s greatest prophets. The prophet Jeremiah in his prophecy concerning the nations says of Edom-

“And Edom shall become an astonishment. Every one that passes by it will be astonished and will hiss at all the plagues thereof. It shall be like the overthrow of Sodom and Gomorrah and the neighbor cities thereof, says the Lord. No man shall abide there, neither shall any son of man dwell therein” (Jeremiah 49-17–18).

The prophet Ezekiel pronounced judgment on Edom with these words- “Thus said the Lord God- I will stretch out my hand against Edom and cut off from it man and beast, and I will lay it in ruins” (Ezekiel 25-13).

The Edomites did not come to Judah’s aid when the Babylonians attacked Jerusalem in the early sixth century B.C.—thus there was no limit to Israel’s enmity. Listen to the prophet Obadiah-

“Thus said my Lord God concerning Edom-

I will make you least among nations,

You shall be most despised.

Your arrogant heart has seduced you,

You who dwell in clefts of the rock,

In your lofty abode.

You think in your heart,

‘Who can pull me down to earth?’

Should you nest as high as the eagle,

Should your eyrie be lodged ’mong the stars,

Even from there I will pull you down

—declares the Lord

…

“For the outrage to your brother Jacob,

Disgrace shall engulf you,

And you shall perish forever.

On that day when you stood aloof,

When aliens carried off his goods,

When foreigners entered his gates

And cast lots for Jerusalem,

You were as one of them.

How could you gaze with glee

On your brother that day,

On his day of calamity!

How could you gloat

Over the people of Judah

On that day of ruin!

How could you loudly jeer

On a day of anguish!

How could you enter the gate of My people

On its day of disaster,

Gaze in glee with the others

On its misfortune

On its day of disaster,

And lay hands on its wealth

On its day of disaster,

How could you stand at the passes

To cut down its fugitives!

How could you betray those who fled

On that day of anguish!

As you did, so shall it be done to you;

Your conduct will be requited!”

Obadiah 1-1–4, 10–15

Other prophets, such as Isaiah, Joel, Amos and Malachi, also vented their wrath on Edom.

The earliest archaeological evidence for the Edomite tribes in the land of Edom was discovered by the American rabbi-archaeologist Nelson Gluecke in the 1930s and 1940. In his surveys east of the Jordan, Glueck identified as Edomite some sites he dated to the 13th to 12th centuries B.C. This was the same period when other Semitic peoples—such as the Moabites and the Ammonites (east of the Jordan) and the Israelites (west of the Jordan)—were consolidating their tribal units into what we might call proto-nations. Glueck correctly identified some of the pottery as Edomite, but it is dated to a much later period—the eighth to seventh centuries B.C. The archaeological evidence from the 13th to 12th centuries in the territory of Edom is rather sparse, but it does point to some kind of early occupation.1

This archaeological evidence is supplemented by an Egyptian papyrus document (Papyrus Anastasi VI) dating to the end of the 13th century B.C., in which an Egyptian official, who is overseeing the frontier, reports on certain Shasu tribes in Edom. According to this report, “[We] have finished letting the Shasu tribes of Edom pass the fortress (of) Mer-ne-Ptah Hotep-hisr-Maat. Life, prosperity, [and] health, which is [in] Tjeku. … ”

This report, one of a group that served as models for schoolboys, presents the form in which an official on the eastern frontier of Egypt would report the passage of Edomite tribes into the better pasturage of the Delta.

Strangely enough, that is the only extra-Biblical source that sheds any light on the Edomites in this period.

The next extra-Biblical reference to Edom comes from Assyria 400 years later. The gap can possibly be explained by the fact that there were no campaigns against Edom either by the Assyrians or by the Egyptians during this period. After this gap, several Assyrian rulers refer to Edom or Edomite kings in their victory inscriptions. Adad-nirari (reigned 810–783 B.C.) mentions Edom in his list of conquests. Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 B.C.) campaigned in Syria-Palestine and subdued a number of rulers who paid him tribute, including Qosmalaku, king of Edom (spelled U-du-mu-a-a in Akkadian cuneiform). In 712 B.C., Sargon II fought against a coalition of states in the region, including Ashdod, Judah, Moab and Edom.

After his famous campaign against Judah in 701 B.C., Sennacherib tells us that Aiaramu, king of Edom, was among those who paid tribute to him. During the reign of Esarhaddon (680–669 B.C.), Qosgabri, king of Edom, is mentioned among the 12 kings of the region who contributed money toward the construction of Esarhaddon’s royal palace in Nineveh. This same king of Edom is mentioned again during the reign of Esarhaddon’s successor, Ashurbanipal (668–633 B.C.). The beginning of this same king’s name (Qosg … ) was also found on a seal impression excavated at Uum el-Biyara.f

In a series of Hebrew letters recovered from the excavation of the fortress at Arad by the late Yohanan Aharoni, the Edomites are also mentioned. Aharoni notes that the letters came from stratum VI and suggest that this stratum was destroyed by the Edomites in 595 B.C.g According to Aharoni, the letter mentioning the Edomites is addressed to the Judahite commander of the Arad fort, who is ordered to send soldiers to reinforce the garrison at Ramat Negeb in the eastern Negev, because an attack by the Edomites is anticipated—“lest the Edomites come,” to use the language found on the Hebrew ostracon (an inscribed pottery sherd).

That Edom appears so frequently in inscriptions connected with the Assyrian and Babylonian military campaigns testifies to Edom’s importance as a political power in the eastern Mediterranean world at this time. In the seventh century B.C., Edom was apparently at the height of its cultural and political development. To its neighbor Judah, Edom no doubt loomed as a menace threatening Judah’s very existence, especially as Assyrian power declined (late seventh century B.C.) and as Babylonian pressure on Judah mounted, toward the end of the seventh century.

Pottery from this period that can be identified as Edomite was first identified by Nelson Glueck at Tell el-Kheleifeh, on the northern shore of the Gulf of Eilat.h There Glueck excavated a fort built in the eighth century B.C. and destroyed in the early sixth century B.C. In stratum IV, Glueck found a large quantity of pottery painted with geometric designs, some with triangular knobs and some undecorated plain pottery of distinct shape, all of which markedly differed from contemporaneous Judahite pottery. Glueck denominated this distinctive pottery repertoire as Edomite, and the designation has withstood the test of time.

Similar pottery has now been found at a number of sites on the Edomite plateau, confirming that this pottery is specific to this area. Especially important is an excavation directed by Dr. Crystal Bennett of the British School of Archaeology at Buseirah, which is apparently the Edomite city of Bozrah, mentioned several times in the Bible as the capital of Edom.i A number of archaeological surveys in the area of ancient Edom have also recovered quantities of Edomite pottery. On the basis of this considerable evidence, we can now say that Edomite pottery is richly diverse and technically accomplished.

Edomite pottery has also been found in both the eastern and western Negev in Israelite strata from the seventh and the beginning of the sixth centuries B.C. These sites include Arad, Horvat ‘Uza, Tel Malhata, Tel Ira, Tel Masos and Tel Aroer in the eastern Negev and Tel Sera and Tel Haror in the western Negev. Edomite pottery has been found as far west as the fort at Kadesh-Barnea in the southwest Negev highlands, and in an Iron Age site recently excavated at Hasevah in the Arabah.

At most of these Negev sites, only small quantities of Edomite pottery were found, primarily painted sherds. At three sites, however—Tel Malhata, Tel Aroer and Tel Ira—larger quantities of pottery including some complete undecorated vessels were recovered.

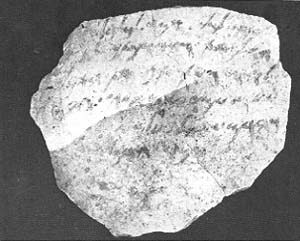

Not only Edomite pottery, but Edomite writing has now been identified. Unfortunately, all these inscriptions are in very fragmentary condition. For this reason their contents tell us very little, but they do tell us a great deal about the paleography of the Edomite script and about the structure of the Edomite dialect.

The largest Edomite inscription yet found is on an ostracon from Tell el-Kheleifeh. It is a fragmentary list of names. First identified as Edomite script by Professor Joseph Naveh of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, it is basically a west Semitic script that reflects the influence of contemporaneous Aramaic script. By the eighth to seventh centuries B.C., this Aramaic script had already begun to penetrate the region along with the Assyrian military campaigns.

Other sites in the Judahite Negev also yielded Edomite inscriptions—two at Tel Aroer and one at Horvat ‘Uza. At Tel Aroer, an inscribed seal and a small Edomite ostracon fragment were found. At Horvat ‘Uza, we found a complete Edomite ostracon.2

The discovery of Edomite pottery and inscriptions at sites in the Judahite Negev naturally raises questions. Obviously, there was some connection between Judah and Edom during the seventh and the beginning of the sixth centuries B.C. Perhaps it consisted of the ordinary commercial relations common between neighboring countries. On the other hand, the Edomite pottery and inscriptions found in the Judahite Negev may have belonged to Edomites who had settled as minority elements among the dominant Judahite population. It might even be possible to interpret the Edomite pottery and inscriptions as evidence of an Edomite conquest of parts of the Judahite Negev.

Based only on the materials I have mentioned, it would be difficult to choose among these three possibilities, possibilities which, incidentally, are not mutually exclusive. But our recent excavation of Horvat Qitmit has convinced me that at least part of the Judahite Negev was at times conquered and occupied by the Edomites.

From the outset, when we first discovered Horvat Qitmit, we knew of its Edomite connection, for some Edomite sherds from the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. were found on the surface among large quantities of other pottery. The fragments of clay figurines and reliefs that were scattered on the surface clearly indicated that this had been a cultic site, destroyed some 2,600 years ago.

After partially excavating the site, we have determined that there was only one archaeological stratum, consisting of two phases.

The site comprises two much-eroded building complexes. The two building complexes are approximately 65 feet apart without any apparent connection. Thus far we have excavated only the southern complex (Complex A), which seems to have contained the main part of the temple.

The temple structure in Complex A consists of three contiguous rectangular rooms, each approximately 6 ½ by 13 feet. Each room opens to the south (the direction of Edom) across its entire width. The middle room is approached by two steps. In the building’s second phase, some of the walls were doubled in thickness (green on the plan) and podiums approximately 3 feet high were added inside each of the three rooms (blue on the plan). The podiums are topped by broad, flat stone slabs.

What purpose did these podiums serve? No structural function is apparent. We may speculate that statues and cult vessels connected with some sacrificial ritual were placed on them.

The crushed chalk floor in each of the three rooms was covered with a layer of ash about a foot thick. On the floor and in the layer of ash, we found huge quantities of pottery sherds, as well as the bones of sheep and possibly goats. Some of the bones even have scratch marks from having been chewed.

About 35 feet south of this temple building was an area enclosed on three sides by straight walls—on all sides except the north; that is, this area opened toward the temple structure. Inside the enclosure was a bamah, a low platform (preserved only to a height of about 16 inches). The bamah was built of medium-size fieldstones set on bedrock. The bamah measured about 4 feet by 3 feet.

Fissures in the bedrock within the enclosure had once been filled with plaster to create a smooth surface; large chunks of dislodged plaster were found strewn about the enclosure area.

Another enclosure, this one circular, was located east of the rectangular enclosure, to complete the structure of Complex A. Inside the circular enclosure, we found a small altar made of flintstones set on a stone base, together with a basin made of fieldstones next to the altar. The basin measured about 3 feet in diameter and was plastered on the inside and over its outer rim. A pit nearly 3 feet deep was hewn out of the bedrock a few feet south of the basin. Animals were no doubt sacrificed on the altar. The basin was probably for water storage. The pit probably served as a drain-pit for the spillover water from the basin or for the blood drained from the animal sacrifices.

The complex as a whole probably served as a diverse cultic center, including not only areas for animal sacrifice, but also for ritual meals, the offering of prayers and the performance of other rites. This is confirmed by the extraordinary finds, mostly from the rectangular enclosure area. There we recovered not only everyday pottery vessels, but also various cultic objects, clay statues and figurines.

The cultic objects included a large quantity of wheel-made, cylindrical, cult stands, mostly painted with designs in red and black. Some of these cult stands were fenestrated (with windows). Others had zoomorphic or humanoid figurines attached to the solid bases or placed on projecting ledges, forming scenes of a cultic nature. The figurines are sometimes hollow and sometimes solid, and they include humans, cattle, sheep and birds. One of the figurines is a human-headed sphinx with a bearded face.

Some of the human figurines portray only the torso, with the lower half of the body represented by a triangular wedge that was evidently inserted in slots in the cult stands or in some other object.

The faces on the human figurines are quite similar. Most are finished by hand, but a few are made from a mold. Some of the human features of the anthropomorphically shaped stands, such as noses and hands, are practically life size. Altogether they have a remarkable sculptural quality.

According to Professor Pirhiya Beck, who is currently studying the iconography of these cult stands, the warrior figures represent the people who placed them in the temple to serve as their surrogates; there the surrogates would constantly worship the Edomite god, calling down his blessing on the person represented by the figurine.

Human figures in the shape of vessels (anthropomorphic vessels) have been found at contemporaneous Israelite sites (for example, at Gezer and Beth-Shemesh), but none is parallel to the Qitmit figurines, except a fragment from Tel Erani. The Tel Erani fragment has a bearded head equal in size to the heads on our stands from Horvat Qitmit. This fragment appears to have once been attached either to a vessel or perhaps even to a cult stand. Cult stands with scenes using human and animal figures are known in the ancient Near East as early as the third millennium B.C. The best known is the famous stand from Tel Ta’anakh from the Late Bronze Age. Another example, found in the Iron Age level at Ashdod, features human figures—musicians, in this case—in the fenestrations.j

Other cultic vessels from Qitmit include three pottery chalices decorated with pomegranates. One of the chalices has an intact pomegranate with traces of six more pomegranates that were once attached around the outside of the vessel. The pomegranate motif was widespread in the ancient Near East from very early times and often appears in a ritual context, probably representing fertility because of the pomegranate’s many seeds.

We also found miniature altars decorated at the top with rounded knobs, and fragments of perforated incense-burning cups of a kind commonly found at Transjordanian sites, particularly at Tell el-Kheleifeh. This latter type of altar has three short legs and holes in the walls.

Another noteworthy find from the rectangular enclosure was a stone seal on which was depicted a figure dressed in a long gown, with one hand raised heavenwards in a gesture of supplication or blessing. Similar representations have been found on numerous seals throughout the Near East dating from different periods. This seal probably belonged to one of the Edomite priests who served at Qitmit. To the priests, or perhaps to the worshippers, belonged numerous bronze finger-rings and crescent-shaped earrings found in our excavation.

Five inscribed sherds, parts of whole vessels and of a cult stand, were also found in the excavation, one in Complex A and four in Complex B. All of the inscriptions are unfortunately very fragmentary. Two, however, belong to a single text that was incised after firing. It probably came from a cult stand. What remains of the text is a single line that, standing alone, yields no meaning; however, it does contain the name of the principal Edomite god Qos (QWS). The paleography of the script on all the sherds is similar to contemporaneous inscriptions from eastern Transjordan, and thus may reasonably be assumed to be in the Edomite script.

But the most extraordinary of our finds from Horvat Qitmit was a three-horned goddess figurine, also found in the rectangular enclosure. One curved horn was placed at each side of the head, and a third sprouts from the middle of the goddess’s forehead. Professor Beck has described this goddess in greater detail in the sidebar.

In my earlier discussion of the Edomite pottery from the seventh to early sixth centuries B.C., I noted that it was found in large quantities at Transjordanian sites within the territory of Edom, as described in the Bible. This same pottery has been found in small quantities at nearly all sites in the Biblical Negev, in strata dating to the late seventh to early sixth centuries B.C. At Horvat Qitmit, however, the proportion of Edomite pottery is several times greater than at other Negev sites. This must be regarded as the determining factor in the site’s cultural attribution. In short, Qitmit was an Edomite cult-center, and the area around it must have been controlled by the Edomites. Qitmit cannot be explained either on the basis of ordinary trade relations or as a small community of Edomites living in a Judahite settlement. Moreover, Qitmit existed for some time, as reflected in its solid construction and its two phases.

Qitmit was constructed during the last days of the kingdom of Judah. It may have continued in use for some years after the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of the Judahite population.

What can we make of this Edomite shrine in the heart of the Judahite settlement of the eastern Negev? It attests to the continued struggle between Judah and Edom since the peoples emerged as nations, a struggle amply reflected in the Bible. The Biblical evidence must reflect the historical reality of the period of the Judahite kingdom. From the Biblical evidence and the evidence from Qitmit, it may fairly be assumed that Edom invaded and conquered extensive Judahite territory in the eastern Negev some time near the fall of Jerusalem, either before or after, taking advantage of Judah’s weakness. This Edomite invasion of the eastern Negev was a prelude to the further expansion of Edomite settlement into the Hebron highlands, the southern Shephelah.k and the northern Negev. Finally in the Hellenistic period (337–37 B.C.), and probably already in the Persian period, the Edomite position in Judah was “legitimized.” This formerly Judahite area, now settled by the Edomites, became officially known as “Edumea” or Idumea. The Edomite cult-center at Horvat Qitmit represents an important stage of this Edomite expansion into Judah.

a. On behalf of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, and the Israel Department of Antiquities.

b. I named the site after a small wadi at the foot of the site, named Wadi Qatamat in Arabic and Nahal Qitmit in Hebrew. “Qatamat” in Arabic means dusty, ashy sand. The Hebrew name is derived from the Mishnah and means ashes.

c. The expedition was directed by the author and included students of Tel Aviv University’s Institute of Archaeology, as well as a number of volunteers. The scientific team included Dani Weiss and Dani Goldschmidt, area supervisors; Liora Freud, area supervisor and registrar; Joseph Kapelyan, surveyor and drawer of finds; Moshe Weinberg and Avraham Hay, photographers. The pottery restoration was carried out in the institute’s laboratory by Naomi Nedav, Mira Barak, Yona Shapira and Rahel Pelta.

d. A wadi is a dry river or streambed that flows only as a result of flash floods in winter.

e. See Floyd S. Fierman, “Rabbi Nelson Glueck—An Archaeologist’s Secret Life in the Service of the OSS,” BAR 12-05.

f. The seal impression reads- LQOSG[BR] MLK’[DM], “Belonging to Qosg[br] King of E[dom].”

g. See Anson F. Rainey, “The Saga of Eliashib,” BAR 13-02.

h. Gary D. Pratico, “Where is Ezion-Geber? A Reappraisal of the Site Archaeologist Nelson Glueck Identified as King Solomon’s Red Sea Port,” BAR 12-05.

i. Other sites in the area of Edom where Edomite pottery has been found include Umm el-Biyara (perhaps Biblical Selah), Tawilan and a small site named Ghrareh, about 12 miles south of Petra.

j. For photographs and discussions of these two stands, see LaMoine F. DeVries, “Cult Stands—A Bewildering Variety of Shapes and Sizes,” BAR 13-04.

k. The Shephaleh is the Biblical term for the low hilly area between the Judean mountains and the coastal plain.

1. More recent evidence contradicts Glueck’s conclusion that the land of Edom was unoccupied between the beginning of the second millennium B.C. and the end of the 13th century B.C. Glueck’s conclusion, which is no longer accepted, supported a late date for the Israelite conquest of Canaan because prior to the 13th century the area was unoccupied. The Bible records that the Israelites met resistance from several peoples in this area on their march to Canaan. In the last decade, as a result of extensive archaeological surveys in Jordan, many sites dating to Middle Bronze II and Late Bronze periods have been discovered in the land of Edom, Moab and Ammon. Glueck’s conclusion must therefore be modified. (See James A. Sauer, “Transjordan in the Bronze and Iron Ages- A Critique of Glueck’s Synthesis,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Research 263 (1986), pp. 1–26; see also John J. Bimson and David Livingston, “Redating the Exodus,” BAR 13-05, pp. 40–53, 66–68; and Baruch Halpern, “Radical Exodus Redating Fatally Flawed,” BAR 13-06, pp. 56–61.)

2. Itzhaq Beit-Arieh and Bruce Gesson, “An Edomite Ostracon from Horvat ‘Uza,” Tel Aviv 12 (1985), pp. 96–101.