The story of the return of the Jewish people to Israel in the sixth century BCE begins with a rather eccentric king by the name of Nabonidus. Nabonidus, the son of Belshazzar, served as a minister for many years in the court of Nebuchadnezzar and eventually became the final king to rule over Babylonia. He ascended the Babylonian throne in the year 556 BCE at age 60 and ruled for seventeen years.

The story of the return of the Jewish people to Israel in the sixth century BCE begins with a rather eccentric king by the name of Nabonidus. Nabonidus, the son of Belshazzar, served as a minister for many years in the court of Nebuchadnezzar and eventually became the final king to rule over Babylonia. He ascended the Babylonian throne in the year 556 BCE at age 60 and ruled for seventeen years.

His widely accepted portrayal as an eccentric is illustrated by a Babylonian inscription which relates his rise to power-

At the beginning of my lasting kingship they revealed a dream to me. “Marduk, the great lord, and Sin, the light of heaven and earth, stood one on either side. Marduk said to me, ‘Nabonidus, king of Babylon, carry up bricks with thy horses and chariots, and restore E.HUL.HUL; make Sin, the great lord, to dwell in his abode.’ Fearfully I spoke to the lord of the gods, saying, ‘O Marduk, that temple which thou dost command me to rebuild, the Umman-manda surrounds it and he is exceeding strong.’ Then Marduk said to me, ‘The Umman-manda of whom thou speakest shall no longer be, neither he nor his land nor the kings who ac-company him.” (Smith 1924, 44)

Nabonidus awoke from his dream and, with this authorization from Marduk, began to build temples to the moon god Sin and to supplant the worship of Marduk with the worship of Sin. This reformation, in his eyes, had the approval of the gods and he undertook it with full force.

It appears that Nabonidus was quite a charismatic iconoclast. He rapidly cast his influence upon his constituents. But, as is often the case, his religious revolution was not without opposition. The priests of Marduk were now unemployed and their authority had been entirely undermined. Their resentment is recorded in what is called the Verse Account of Nabonidus, a libel which accuses him of mendacity, madness and impiety. It vituperatively mocks the king as one who, although entirely illiterate, believes he received prophecy.

In addition to the priests’ opposition, a schism developed between the palace and the people, who had heavy taxes levied upon them in order to fund the building of the new temples to Sin. This ultimately led to a form of silent revolution. The disgruntled priests of Marduk arranged a secret pact with the new power of the East, a young general named Cyrus, the son of Cambyses I. In 559 BCE, Cyrus conquered Media, Asia Minor, spreading his dominion from the Caspian Sea to India. On the fifteenth day of Tashritu (Tishre), 539 BCE, Cyrus entered Babylon and, with the help of the priests, took over the city without bloodshed. Nabonidus was dethroned (presumably he fled) and, true to his word, Cyrus allowed the priests of Marduk to restore their former worship.

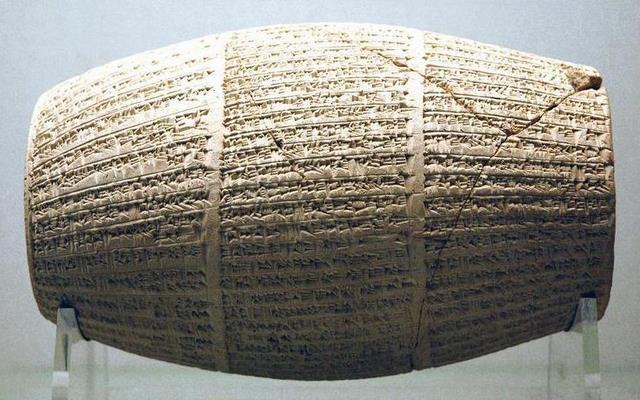

Recognizing his great success in Babylonia, Cyrus chose to turn this method into strategy. He would allow local residents to restore their ancestral faith and practice their religions freely in return for peaceful political takeover. This policy is recorded in what is known as the Cyrus Cylinder. The text reads as follows-

I am Cyrus, king of the world, great king, legitimate king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four rims (of the earth), son of Cambyses … whose rule Bel and Nebo love, whom they want as king to please their hearts.

When I entered Babylon as a friend and (when) I established the seat of the government in the palace of the ruler under jubilation and rejoicing, Marduk, the great lord, [induced] the magnanimous inhabitants of Babylon [to love me], and I was daily endeavoring to worship him. My numerous troops walked around in Babylon in peace, I did not allow anybody to terrorize (any place) … I strove for peace in Babylon and in all his (other) sacred cities.

… I returned to (these) sacred cities on the other side of the Tigris, the sanctuaries of which have been ruins for a long time, the images which (used) to live therein and established for them permanent sanctuaries … Furthermore, I resettled upon the command of Marduk, the great lord, all the gods of Sumer and Akkad whom Nabonidus has brought into Babylon to the anger of the lord of the gods, unharmed, in their (former) chapels, the places which make them happy. (Pritchard 1955, 316)

Restoring the former worship brought happiness to the gods and served Cyrus well politically and militarily. He was able to bring peace to Babylon and his soldiers strolled freely through the city. All of this serves as significant backdrop for Ezra chapter 1, otherwise known as the Cyrus Declaration of 538 BCE.

In the first year of King Cyrus of Persia, when the word of the Lord spoken by Jeremiah was fulfilled, the Lord roused the spirit of King Cyrus of Persia to issue a proclamation throughout his realm by word of mouth and in writing as follows-

“Thus said King Cyrus of Persia- The Lord God of Heaven has given me all of the kingdoms of the earth and has charged me with building Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Anyone of you of all His people — may his God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem that is in Judah and build the House of the Lord God of Israel, the God that is in Jerusalem; and all who stay behind, wherever he may be living, let the people of his place assist him with silver, gold, goods, and livestock, besides the freewill offering to the House of God that is in Jerusalem.” (Ezra 1-1–4)

Rather than simply paraphrasing the policy outlined in the Cyrus Cylinder, the Bible stresses the motivation for his actions using the phrase, “the Lord roused the spirit of King Cyrus.” The invitation which Cyrus extended to the Jewish people to return to their ancestral homeland and rebuild the Temple was not, in this view, a result of astute political planning but rather a function of the spirit of the Lord. In fact, beyond this passage in Isaiah 44-28 and 45-1, Cyrus is called God’s “anointed one” and his “shepherd.” He is described as an instrument for the realization of the redemption of Israel through the will of God. These verses lend themselves to the belief that the Bible is a theological commentary on history rather than simply a history book.

It is hard to accurately state how many Jews returned to Zion. The estimate is that 49,000 Jews returned in the first wave in 538 BCE and that another 3,000 came to Israel in a second wave. The estimate is thus at approximately 52,000 Jews returning to Israel. It is also difficult to assess the proportion of the total Jewish population which had returned. (John Bright, A History of Israel, pp. 360–372.) Presumably, it was not a particularly impressive showing. However, the activities of the returned exiles were themselves remarkable.

The third chapter of Ezra describes the Jews’ building of an altar. The significance of this ac-tion cannot be underestimated. The people had not only returned to their land; through re-building the altar they had reestablished their spiritual connection to its holiness. Although it would be nearly twenty years before the Temple was finally built, the process had begun. The actions call to mind a day in Basel, Switzerland. Theodore Herzl wrote in his diary of Sept. 3rd, 1897-

If I were to sum up the congress in a word — which I shall take care not to publish — it would be this- At Basel I founded the Jewish state. If I said this out loud today I would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive it. (Lowenthal 1956, 224)

As history confirms, fifty years hence—in 1948—all recognized that day as the initial establishment of the State of Israel. So too, the building of the altar by the returnees in 538 BCE was the first step in the establishment of the Jewish state.

With such auspicious beginnings, subsequent events were somewhat disappointing. The Jewish people had come home, the altar was rebuilt, Zion restored and the building of the Temple was planned. The courage and faith of a select few had saved Israel from demise. Sadly, how-ever, the road was not smooth for the returnees. First, the Samaritans in the north accused the newcomers of sedition, appealing to the Persians to retract their royal permission to rebuild the Temple. Additionally, the Arab conquest of Edom had let to the Edomite occupation of southern Israel, creating a situation fraught with tension for the Jewish people. In fact, the Is-rael to which the exiles returned was just twenty-five miles from north to south. The new community in Zion was dogged by famine, crop failure, and pestilence; it would be another eighteen years until the poor and dispirited people would once again take up the challenge of rebuilding the Temple.

Cyrus was succeeded by his son who, like his grandfather, was named Cambyses. Cambyses II headed a regional crusade which brought him all the way to Egypt. While in Egypt, he was informed that Gaumata had usurped his throne in his absence and conquered all of the Eastern provinces. The news drove him to suicide. In 520 BCE, Darius, an officer in the royal court and relative of the royal family, took over. He killed Gaumata, quelling the revolt in Persia. These historical events deeply affected the Jewish people’s impression of the Persian Empire. The immutability of the Empire’s power base was now thrown into question. In a new world in which edicts could be revoked and empires overturned, the Jews felt that possibilities were different- Perhaps the Temple could be rebuilt.

The prophet Haggai spurred along the situation already set into motion by political develop-ments. In the first chapter of the Book of Haggai, the prophet appealed to the tired and poor masses and attempted to shake their apathy, feeling that they had resigned themselves to a life with no Temple. He was successful in encouraging the community to take up the challenge and actualize the dream of building the second Temple and by March of 515 BCE the Temple was completed. However, the second Temple was of a lower standard than the first, and the Jews in Israel were disappointed. The prophet tried to help them maintain perspective-

But be strong, O Zerubbabel,—says the Lord—be strong, O high priest Joshua son of Jehozadak; be strong, all you people of the land—says the Lord—and act! For I am with you—says the Lord of Hosts. So I promised you when you came out of Egypt, and My Spirit is still in your midst. Fear not! … The glory of this latter House shall be greater than that of the former one, said the Lord of Hosts; and in this place I will grant prosperity—declares the Lord of hosts. (Haggai 2-4–5, 9)

The prophet prevailed upon the people to change their attitude, explaining that, while the physical structure of the Temple might pale in comparison with that of Solomon, God would suffuse the house with glory if the people would work towards its rebuilding.

This notion was even translated into halakha. Maimonides (Hilchot Beit HaBechira 6-16) distinguishes between what is called sanctity of the first phase (kedusha rishona) and sanctity of the second phase (kedusha shinia). The first phase refers to land sanctified through conquest, the second phase to land sanctified through settlement during the time of the return to Zion. In contrast to the conquest at the time of Joshua, which was characterized by intimate Divine guidance and intervention, the settlement by the returned exiles received only general prophetic instruction. The sanctification through settlement, a direct function of people’s actions, served to override the original sanctification, a clear indication that Haggai’s words held true. The active role of the Jewish people breathed spiritual grandeur into the new House of God and into the reconstituted settlement in the Land of Israel.

Works Cited-

Smith, Sidney, trans. 1924. Babylonian Historical Texts- relating to the capture and downfall of Babylon. London- Methuen & Co.

Lowenthal, Marvin, ed. 1956. The Diaries of Theodor Herzl- edited and translated with an introduction by Marvin Lowenthal. New York- Dial Press.

Pritchard, James B., ed. 1955. Ancient Near Eastern Texts- relating to the Old Testament (Princeton, NJ- Princeton University Press.

JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh- The Tradition Hebrew Text and the New JPS Translation – second edition. 1999. Philadelphia- The Jewish Publication Society.

Appendix

English translation to the Rambam– Hilchot Beit HaBechira 6-16

The Code of Maimonides Book 8- The Book of the Temple Service

Translated from the Hebrew by Mendell Lewittes

Yale Judaica Series vol. XII

Yale University Press- New Haven, 1957.

Treatise One- The Temple

Chapter 6; Section 16, pp 28–29

Now why is it my contention that as far as the Sanctuary and Jerusalem were concerned the first sanctification hallowed them for all time to come, whereas the sanctification of the rest of the Land of Israel, which involved the laws of the Sabbatical year and tithes and like matters, did not hallow the land for all time to come? Because the sanctity of the Sanctuary and of Jerusalem derives from the Divine Presence, which could not be banished. Does it not say and I will bring your sanctuaries unto desolation (Lev. 26-31), wherefrom the Sages have averred- even though they are desolate, the sanctuaries retain their pristine holiness.

By contrast, the obligations arising out of the Land as far as the Sabbatical year and the tithes are concerned had derived from the conquest of the land by the people (of Israel), and as soon as the Land was wrested from them the conquest was nullified. Consequently, the Land was exempted by the Law from tithes and from (the restrictions of) the Sabbatical year, for it was no longer deemed the Land of Israel.

When Ezra, however, came up and hallowed (the land), he hallowed it not by conquest but merely by the act of taking possession. Therefore, every place that was possessed by those who had come up from Babylonia and hallowed by the second sanctification of Ezra is holy today, even though the land was later wrested from them; and the laws of the Sabbatical year and the tithes appertain thereto in the manner we have described in Laws Concerning Heave Offerings.