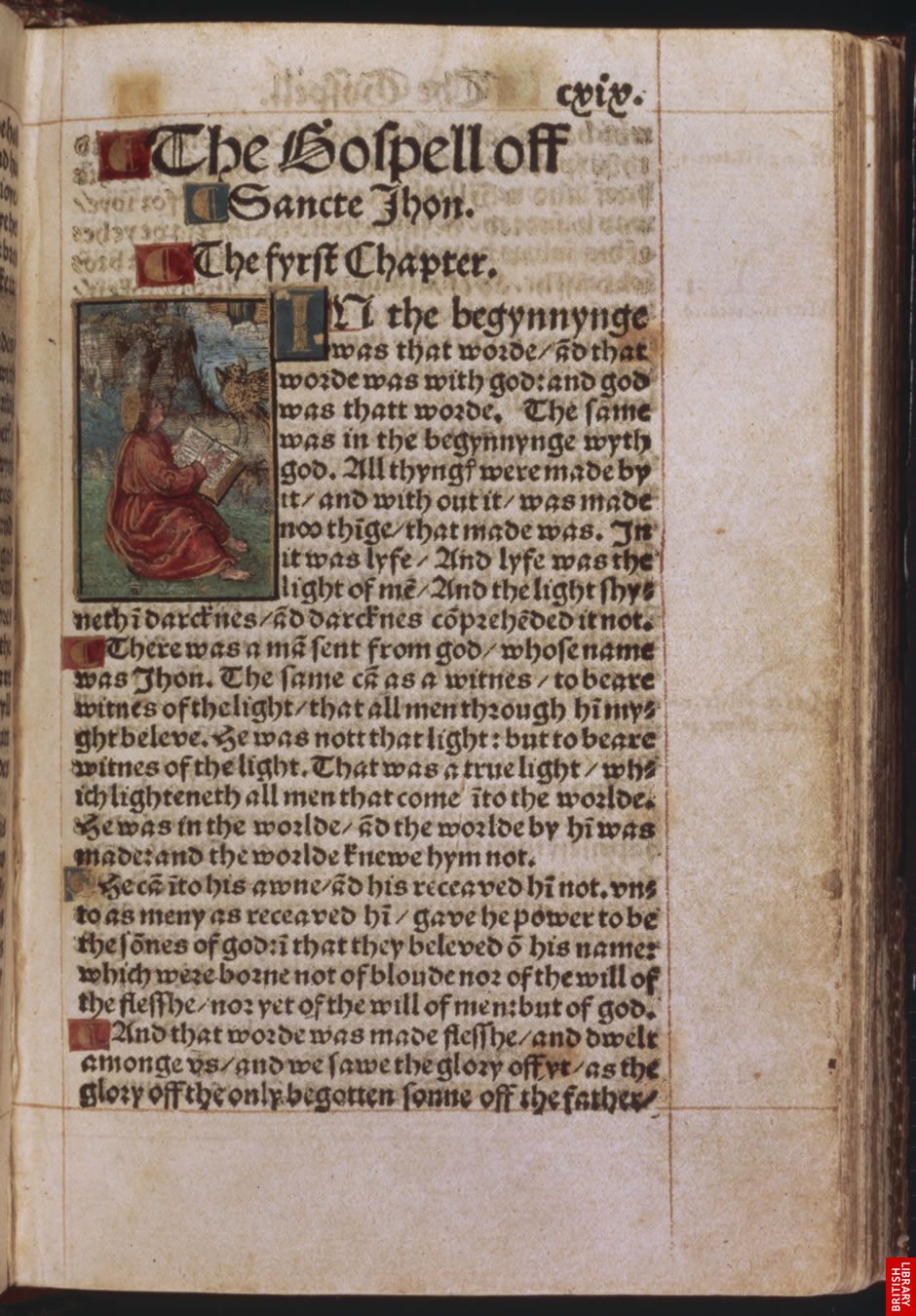

Tyndale’s New Testament was the first to be printed in English. This is one of only two complete copies surviving from the 3,000 or more printed in 1526 by Peter Schoeffer in the German city of Worms. Tyndale’s translation was pronounced heretical in England, so his Bibles were smuggled into the country in bales of cloth. Those discovered owning them were punished. At first only the books were destroyed, but soon heretics would be burned too – including Tyndale himself in 1536.

Tyndale was a scholar and theologian who was born in Gloucestershire at the end of the 15th century. Tyndale was educated at Oxford and then at Cambridge. An impressive scholar, fluent in eight languages, he was ordained as a Christian priest in around 1521. As a chaplain back in Gloucestershire, he was influenced by the writings of Dutchman Desiderius Erasmus, who argued for personal faith between the individual and God, not mediated and controlled by the Church hierarchy.

But such views, and Tyndale’s plans to translate the New Testament into English, were unpopular with the clergy. He fled to London in 1523 and tried unsuccessfully to find support from the bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstal.

Although the Old Testament had first been written in Hebrew and the New Testament in a dialect of Greek and, possibly, Aramaic, the official language of the medieval Church was Latin – the language of the Roman Empire, which had adopted Christianity as its religion during the fourth century.

Christians continued to be governed from Rome by the Pope during medieval times. Church services were conducted in Latin throughout the Christian world, and translation of the Latin Bible into the vernacular, in other words the local language anyone could understand, was actively discouraged.

None the less, by Tyndale’s day, vernacular Bibles were available in parts of Europe, where they added fuel to the popular questioning of religious authority initiated by the monk Martin Luther – a religious crisis known as the Reformation, which resulted in the splitting of Christianity into Catholic and Protestant Churches.

In England, however, under the 1408 Constitutions of Oxford, it was strictly forbidden to translate the Bible into the native tongue. This ban was vigorously enforced by Cardinal Wolsey and the Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas More, in an attempt to prevent the rise of English ‘Lutheranism’. The only authorised version of the Bible was St Jerome’s Latin translation, known as the ‘Vulgate’, made in the fourth century and understood only by highly-educated people.

Tyndale’s mission was to make the Bible accessible to all. His translation was undeniably Lutheran in tone, replacing traditional words with new ones that argued a shift in the balance of religious power- ‘Congregation’ instead of Church; ‘elder’ in place of priest; and ‘repentance’ for penance.

Though spurned by the clergy and in constant danger, Tyndale made influential friends among the laity. In May of 1524, aided by money from Sir Humphrey Monmouth and others, he set sail for Germany where he hoped his secret work could be continued in greater safety.

He based his translation on a New Testament in Greek that had recently been complied by Erasmus from several manuscripts older and more authoritative than the Latin Vulgate.

Printing began in Cologne in the summer of 1525, but wind of the project soon reached the Dean of Frankfurt. He not only arranged a ban on printing in Cologne but also alerted Cardinal Wolsey to Tyndale’s activities. Tyndale fled with his assistant, William Roy, to Worms, where a pocket-sized edition was the first of two to be completed. By April 1526, Tyndale’s New Testament was being read behind closed doors in England.

Tyndale had already begun translating the Old Testament with the financial backing of a few English traders. When Cardinal Wolsey died, he judged it safe to move to Antwerp in 1534 and live there openly. But he was betrayed by a spy called Henry Philips, and imprisoned in Vilvoorde Castle, accused by Henry VIII of spreading sedition in England. In 1536 he was strangled and burned at the stake.

Yet already, members of the royal family – Anne Boleyn, in fact – were openly reading Tyndale’s text. More English-language printed Bibles appeared, and by 1611 they had gone from being prohibited to being officially sanctioned, when the King James Authorised Bible appeared.

The British Library bought what it called “the most important printed book in the English language” for a little over a million pounds in 1994. When Lord Oxford bought it for his collection in the 1700s, it had cost him just 20 guineas.

British Library- Tyndale’s New Testament

See also-