The expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290 was not only the first of the great medieval expulsions, but was also one of the most thorough. Whereas in other countries and areas, even after expulsion, small groups of Jews living clandestine lives could often be found, the case in England was different. For more than three hundred years we hear of virtually no Jews in the country.

The expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290 was not only the first of the great medieval expulsions, but was also one of the most thorough. Whereas in other countries and areas, even after expulsion, small groups of Jews living clandestine lives could often be found, the case in England was different. For more than three hundred years we hear of virtually no Jews in the country.

In the years after the expulsion from Spain, occasional New Christians found their way to England, and we hear of one or two small groups, in London and Bristol, but these were all outwardly Christians and many of them were undoubtedly genuine Christians through and through.

Like so many other countries of Europe in the sixteenth century, England was going through its own religious struggles. Added to the usual post-Reformation tension between Catholics and the new Protestant groupings, there was another trend at work. In the early sixteenth century, the English crown pushed Catholic England to break with the authority of the pope. A Church of England was declared, still Catholic (although reformed in various ways), but independent. This was the start of a veritable seesaw of changing religious allegiances by the independent Church.

It seemed that every monarch was determined to take the new English Church in a different direction. Starting Catholic, then Protestant, then Catholic, then Protestant again, the Church swung backwards and forwards through three decades. By the late sixteenth century, the Church was firmly Protestant in a very English kind of way; doctrine was ambiguously defined, practice was not too dogmatic.

However, a more radical strain of Protestant thought, which went by the name of Puritanism, calling for a purification of the Church from all hints of the hated Catholicism, was becoming increasingly vocal. They were, of course, not the only ones who hated the Catholics. By this time Catholicism, which lived a semi-underground existence, was defined as the enemy; since it was associated with Spain and Portugal more than anywhere else, the Spanish speaking New Christians-most of whom seem to have appeared as Catholics-were doubly suspect. The government took action against them in 1609 and many fled the country. However, in the first part of the seventeenth century there were still small groups living in England, especially in London.

Meanwhile, the religious climate in England was becoming more radical. In an increasingly more complex situation where religious, economic and political factors became more and more intertwined, the Puritan influence grew from strength to strength. In 1642, a Civil War broke out between supporters of King Charles I and supporters of the Puritan group in Parliament. Some seven years later, the King was tried as an enemy of the people and beheaded. England was a Republic.

The “strongman” of the republic was the devout Puritan and soldier, Oliver Cromwell. From the death of the King in 1649 till his death in 1658, the country went through extensive changes in its political structure, but Cromwell was the central figure throughout. In December 1653, when a new constitution brought in a form of semi-monarchy, ruled by a Lord Protector, together with a Council and Parliament, Cromwell filled the role.

The Puritans in England were one of the strongest groups of Messianic believers in the entire Christian world. They were convinced that the days of the Messiah were drawing close, and many of their scholars had calculated a variety of mid-seventeenth century dates as the projected time of Christ’s return.

The Puritans were great biblical scholars, and identified strongly not just with the New Testament, like all Christians, but very much with the Old Testament, drawing upon the great military figures of biblical history for their inspiration. The Judges, Joshua, David, were all figures who had fought for their faith, and the Puritans identified with this alliance of military strength and divine faith. They regarded themselves as God’s army, and this self-perception led to an increasing regard for the Hebrews of old, their literature, the Bible, and their language, Hebrew.

For many of them, as for other committed Protestants, the enthusiasm for the Bible and its people, the Jews, stopped over 1500 years earlier when the Jews, according to Christian belief, had been superseded by Christians as God’s people. The intense interest evinced by groups like the Puritans, however, brought some of them to a less jaundiced picture of the Jews. Thus we find a new openness in certain Puritan (and other extreme European Protestant) circles towards the contemporary Jewish condition, especially as the Messianic expectation increasingly gripped them.

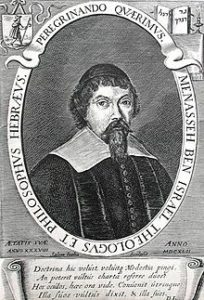

Menasseh ben Israel was aware of this. The son of an escapee from the Portuguese Inquisition who was living at this time in Amsterdam (at the same time as Uriel da Costa), he had come there as a child, a Christian boy named Manuel Dias Soeiro. Since then, as a Jew, Menasseh had proved himself to be extremely talented in his studies, and he had been given a position as preacher in the community when he was only eighteen. His interests lay not so much in the Talmudic sphere, like so many of his contemporaries, but rather in theological, mystical and philosophical directions. These interests and his extensive knowledge of languages, oriented him perhaps more than any other Jew of his age towards an interest in and a knowledge of goings-on in the outside world. He started publishing his writings (on his own printing press) in a number of languages and these writings brought him international fame among non-Jewish scholars who corresponded with him from all across Europe on a vast number of different issues.

Menasseh, like all Jews, was drawn to the idea of the Messianic coming, and felt-through hints in the great Spanish Jewish mystical work, the Zohar-that the Messianic time was drawing near. He constantly looked for signs of the Messiah, including hints of the existence of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, exiled from their homeland over 2000 years previously and never discovered. The Messiah could only come if all the tribes were ready. He became convinced on hearing various rumours and reports, that the tribes existed. To him, it was clear that conditions were drawing near for a Messianic coming.

The Jewish world itself was in chaos. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were being slaughtered in the Ukraine in the terrible Polish wars of the midseventeenth century. The Inquisition was still seeking out victims.

New havens were needed for the Jews. Moreover, Menasseh believed that the Messiah could only come when Jews were found in all the corners of the world. These two ideas came together in his mind because there was one edge of the civilized world where there were no Jews-and that was England.

England, at the western edge of Europe, was Jew-less. Menasseh knew from his correspondents that Messianic excitement was running high among the Puritans of England. He had received letters from English scholars telling him of the turmoil in the land. He knew that Cromwell was not only a devout Puritan, but also a humane and tolerant man.

He decided to petition Cromwell to allow Jews to settle in England. He would marshal all the arguments at his disposal, the theological as well as the merely practical. And he was nothing if not eloquent. He wrote letters, books and petitions, sent representatives, and finally in 1655 he went there himself, presenting to Cromwell a petition for the readmittance of the Jews into England.

“Three things, if it please your Highness, there are that make a strange Nation well-beloved amongst the natives of a land where they dwell- Profit, that they may receive from them; Loyalty, that the strangers hold towards the Princes of the country and the Nobility, and purity of their blood. Now when I shall have explained that all these three things are found in the Jewish Nation, I shall certainly persuade your Highness that with a favourable eye you shall be pleased to receive again the Nation of the Jews, who in time past lived in England, but whom I know not by what false informations, were cruelly ‘handled and banished.

Profit is a most powerful motive, and one which all the World prefers before all other things- it is a thing confirmed, that merchandising is, as it were, the proper profession of the Nation of the Jews. I attribute this in the first place to the particular Providence and mercy of God towards His people- for having banished them from their own Country, yet not from His Protection, He hath given them, as it were, a natural instinct, by which they might not only gain what is necessary for their need, but that they should also thrive in riches and possessions; whereby they should not only become gracious to their Princes and Lords, but that they should be invited by others to come and dwell in their lands.

Moreover, it cannot be denied, but that necessity stirs up a man’s ability and industry; and that it gives him great incitement, by all means to try the favour of Providence. And the Jews are forced to use merchandising until that time, when they shall return to their own Country.

From that very thing we have said, there rises an infallible profit, commodity and gain to all those Princes in whose lands they dwell.

Now in our dispersion, our Fore-fathers, flying from the Spanish Inquisition, came some of them into HoIland, while others got into Italy, and others betook themselves into Asia; and so easily they give credit to one another, and having perfect knowledge of all the kinds of Money, Diamonds, Cochineal, Indigo, Wines, Oil, and other Commodities, and holding correspondence with their friends and families, whose language they understand; they abundantly enrich the lands and Countries of Strangers, where they live, not only with necessities but also luxuries.

The love that men ordinarily bear to their own Country and the desire they have to end their lives where they had the beginning, is the cause, that most strangers having gotten riches where they are in a foreign land, are commonly taken by a desire to return to their native soil, and there peaceably to enjoy their estate; so when they depart from thence, they carryall away, and spoil them of their wealth; transporting all into their own native Country. But with the Jews the case is different; for where the Jews are once kindly received, they make a firm resolution never to depart from there, seeing they have no proper place of their own- and so they are always with their goods in the cities where they live, a perpetual benefit, to the country.

Therefore, (if it please your Highness) it follows that the Jewish Nation, though scattered through the whole World, are not therefore a despicable people, but a plant worthy to be planted in the whole world and received into populous cities; being trees of most savoury fruit and profit, they should be favoured with laws and privileges, or prerogatives, secured and defended by arms.”

The meeting between the Rabbi from Amsterdam and the English soldier, both gripped by their own different forms of Messianic expectation, must have been dramatic. Cromwell was impressed. He convened a conference of Whitehall to discuss the issue. Menasseh presented his arguments, undoubtably with great eloquence, but his audience was divided. Some were favourable, many not. The conference came out of the fourth session with no agreement, at which point Cromwell dissolved it. No answer was reached; officially at least, the status quo was maintained. Menasseh was crushed.

However, three months later, another petition with Menasseh’s signature attached came before Cromwell. This request, submitted by members of the New Christian community, asked for permission to worship in their own way, unmolested, and to be allowed their own burial ground. This was granted-and paved the way for the de-facto restoration of Jewish worship in England, laying the basis for the Jewish community of the future. Menasseh died soon after his return to Holland, but the community he helped to legitimize lives on today.

Pages 135-140