During the century and a half before the State of Israel was established, the crucial ingredients necessary for creating the State came into being. Those ingredients were expansion of the Jewish population to a critical mass, the collapse of the imperial order in the Middle East, economic and cultural modernization, the development of Zionism, and the emergence of the Jewish question as a central problem in European politics. Many of the difficulties that have faced Israel since its founding also have roots in this period.

During the century and a half before the State of Israel was established, the crucial ingredients necessary for creating the State came into being. Those ingredients were expansion of the Jewish population to a critical mass, the collapse of the imperial order in the Middle East, economic and cultural modernization, the development of Zionism, and the emergence of the Jewish question as a central problem in European politics. Many of the difficulties that have faced Israel since its founding also have roots in this period.

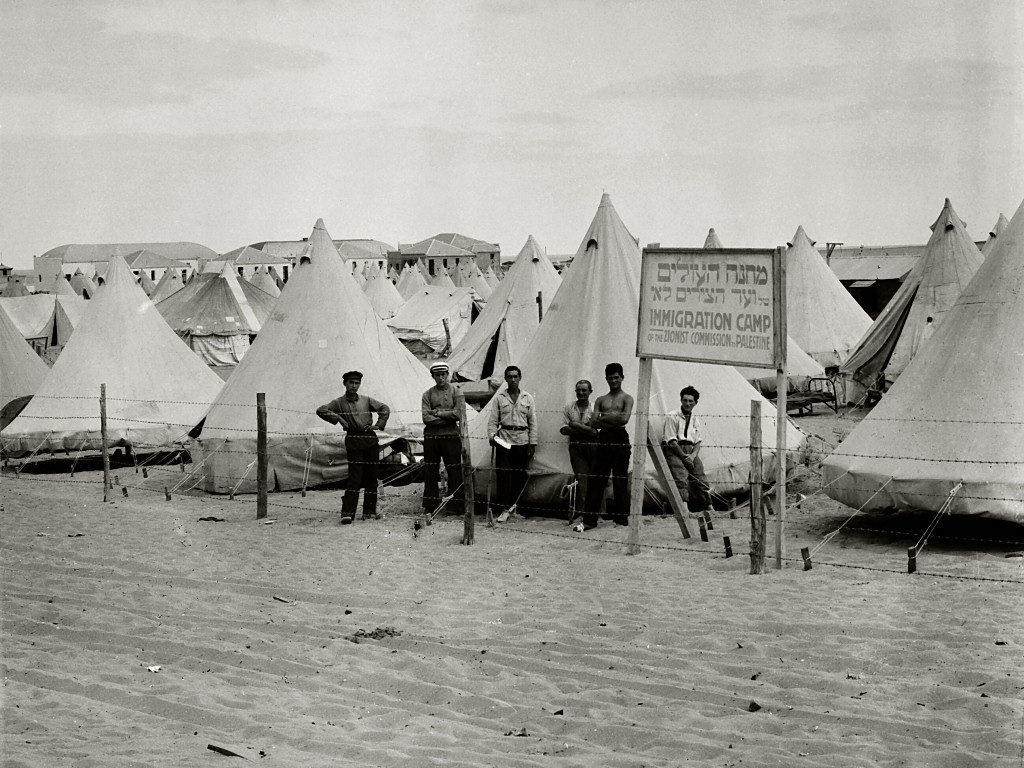

At the beginning of the nineteenth century there were fewer than 5,000 Jews in Palestine out of a total population of 250-300,000. By 1948 the number of Jews had increased 130 times, to 650,000 — more than a third of the country’s 1.85 million residents. Much of that growth was catalyzed by mounting European interest in the region, stimulated in turn by the ongoing decay of the Ottoman Empire and the power vacuum it left in the eastern Mediterranean. The spread of modern steamship transportation helped France, Germany, Russia, and Great Britain develop their economic interests in Palestine, which often brought material benefit to local Jews. After the First World War Britain replaced Turkey as the governing authority, operating under a mandate from the League of Nations to promote the eventual creation in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. During the 1920s and through to the mid-1930s the British mandatory government cooperated with the World Zionist Organization in facilitating large-scale Jewish immigration. It also built up a modern economic and administrative infrastructure in the country, which permitted Palestine to support an ever-expanding population.

Growing numbers of Jews became interested in settling Palestine under the influence of the Zionist movement, which called upon Jews to enter the ranks of modern political nations by returning en masse to their historic homeland in order to claim sovereignty over it. The Zionist message appealed at first mainly to Jews from eastern Europe who, beginning in the 1880s, sought effective ways to overcome mounting threats to their physical security and material wellbeing in that part of the world. From the early twentieth century Palestine served as a site of a series of Zionist-inspired projects aimed at promoting Jews’ economic self-sufficiency and capacity for self-defense — both prerequisites for eventual national independence. The Zionist movement also fostered the creation of a Jewish secular culture anchored in the Hebrew language, which was also regarded as an essential aspect of life in a modern Jewish national state. The rise of Nazism in the 1930s and its influence on policies toward Jews in several other European countries increased the attractiveness of the Zionist project, bringing unprecedented Jewish demand for immigration to Palestine.

However, Zionist expansion under British auspices aroused opposition from Palestine’s Arab majority. Increasingly that opposition was expressed through armed action. Hoping to reduce friction and seeking a solution to Palestine’s political future, Britain ended its partnership with the Zionist movement in 1939, a few months prior to the outbreak of World War II, thus preventing Palestine from becoming a refuge for Jewish refugees from Nazi rule. The ensuing refugee crisis, and later the Holocaust, alienated the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) from the British, and at the end of the World War Britain faced an armed Jewish revolt against the Mandate. The fate of European Jewry helped muster international support for Zionist proposals to concentrate Jewish survivors of Nazism in a Palestinian Jewish state. That support eventually enabled the State of Israel to come into being despite the armed opposition of the Arab world, which continued to resent what they saw as a foreign intrusion into their region.