The Exodus, 1300-1200 BCE

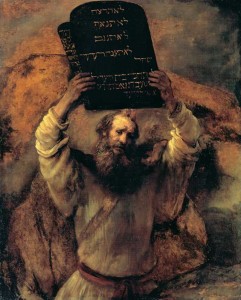

Moses Smashing the Tablets of the Law

While tending sheep for his father-in-law, Moses discovers a bush that was burning but not consumed. It is the beginning of an encounter with the divine. God reveals himself as the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and orders Moses back to Egypt to demand of Pharaoh that he allow the Israelites to worship their God in the desert. Pharaoh refuses, and God unleashes, through his messengers Moses and his brother Aaron, an ever-more devastating series of disasters against the Egyptians and their land. After the tenth and most devastating of theses calamities—the death of all firstborn Egyptian males—Pharaoh finally relents and the Israelites march quickly into the desert. Pharaoh has a change of heart and orders his mighty army to pursue. The Israelites are caught between the Sea of Reeds (Red Sea) and the Egyptian army. Following God’s command, the Israelites march into the sea, which parts just long enough to pass through. When the Egyptians pursue the Israelites, the waters fall back and drown them.

A powerful and exceedingly well-crafted story, but how historical is it?

Many of the details of the Exodus story match the historical and archaeological record. The Egyptians worried about having too many foreigners within their borders. The “Admonitions of Ipuwer” (thought to have been composed sometime in the 19th to 17th centuries B.C.E.) speaks of defenses meant “to repulse the Asiatics, to trample the Bedouin.” The 21st-century “Instructions of Merikare” says that the eastern Delta “abounds with foreigners.”

We also have records of Semitic peoples living in Egypt, including a papyrus that contains a list of more than 40 female slaves with Semitic names. Interestingly, one of those names is Shiphrah, the same name as that of the midwife in Exodus 1 who refused to kill male Israelite newborns.

Another telling detail is that the Exodus story has the Israelites forced into making mudbrick. And, indeed, a 15th-century wallpainting at Thebes depicts Semitic slaves making mudbrick. That was the common building material in Egypt at the time; a later writer living in Canaan could easily have assumed that the Israelites were forced to build Pharaoh’s store-cities using stone, the typical material used in Canaan. A further confirming detail is that the mudbrick mentioned in the Exodus story contains straw; mudbrick in Canaan was made without straw.

An object from about 1275 B.C.E. now called the Louvre Leather Roll records that mudbrick quotas were not being met, a detail that matches Exodus 5-14.

Such details aside, we cannot match any specific event in the Exodus story with anything known to history (that is, outside the Bible itself). We do not know the route the Israelites took out of Egypt or which mountain in the Sinai desert is Mt. Sinai. As mentioned above regarding the Patriarchs, the Biblical chronology is not consistent, giving the length of the Israelite stay in Egypt as 400 years (Genesis 15-13), 430 years (Exodus 12-40-41) and four generations (Genesis 15-16). 1 Kings 1-6 says that Solomon began to build the Jerusalem Temple 480 years after the Israelites left Egypt; because Solomon’s reign is reasonably well established as having begun in 960 B.C.E. and because the building of the Temple began in the fourth year of his reign, the Exodus would have occurred in 1436 B.C.E.

The figure of 480, however, seems to have more of a symbolic role than a historical one. It equals 12 generations of 40 years each, and 40 is a recurring number in the Bible. The wandering in the desert after the Exodus is given as 40 years, and David and Solomon are both said to have reigned for 40 years. Indeed, according to the chronology in the Book of Kings, the length of time from the building of the Temple to the end of the Babylonian Exile was 480 years—again, 12 times 40. The Biblical chronology, then, seems more concerned with placing the Temple at the center of its history than with providing us with historical dates.

There are other problems with placing the Exodus in the 15th century B.C.E. That period was a time of great Egyptian power in Canaan. The Book of Joshua, in contrast, does not even mention Egypt when recounting the Israelite conquest of Canaan. Even more problematic is that there is no archaeological evidence of a new people arriving in Canaan in the late 15th century B.C.E.

A more likely time for the Exodus to have occurred is the 13th century B.C. By that time, Egyptian influence had waned—making it understandable why Joshua makes no mention of it. More important, though, are the many signs of major demographic changes that took place in the central highlands of Canaan in the 13th century. The population expanded significantly and new villages were founded. Terrace agriculture—leveling areas along hillside slopes to allow for planting—became widespread, and cisterns lined with lime plaster to keep water from seeping away also became common.

Further bolstering a 13th-century B.C.E. date for the Exodus (assuming it is a historical event) is the Egyptian evidence. The long-reigning Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279-1213 B.C.E.) looms behind the Exodus story. The Israelites settle in the region of Ramesses (Genesis 47-11) and later build a city by that name (Exodus 1-11); that city later becomes a massing point before they flee into the desert. Ramesses II moved his capital to the northeastern Delta—the same area where the Israelites settled—and he instigated numerous large building projects that required much labor.

Pharaoh Merneptah, the son of Ramesses II, provides the first historical reference to the Israelites. On a black monument dating to 1207 B.C.E. he boasts of his having vanquished various peoples, including the Israelites, during a military campaign in Canaan. By the end of the 13th century B.C.E. the Israelites were known to the mighty ruler of Pharaoh as a people in Canaan. That is why scholars think that century is the most likely candidate for the emergence of the Israelites. But whatever the exact time and nature of their sojourn in Egypt, the Israelites treated their slavery and subsequent escape as central to their understanding of themselves as a people and to their relationship to their God.

Excerpted from Biblical History: From Abraham to Moses, c. 1850-1200 BCE, Steven Feldman, COJS

Overview

- The Mists of Antiquity 2000-1000 BC, Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem- Sacred City of Mankind, Steimatzky Ltd., Jerusalem, 1991.

- Biblical History- From Abraham to Moses, c. 1850-1200 BCE, Steven Feldman, COJS.

- From Egypt to Sinai (Exodus 5-24, 32; Numbers), Christine Hayes, Open Yale Courses (Transcription), 2006.

Primary Sources

Artifacts

-

- Ugaritic Alphabet Tablet, 14th-13th century BCE

- Marzeah Tablet, c. mid-14th century BCE

- The Story of Moses, 1330-1210 BCE

- The Capture of Joppa, c. 1300 BCE

- Book of the Dead, c. 1300 BCE

- Page from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer, c. 1300 BCE

- The Construction of Pithom, 1292-1225 BCE

- Stele of Seti, 1294-1279 BCE

- Abydos King List, 1294-1279 BCE

- Mummy of Seti, 1279 BCE

- Turin King List, 1279-1213 BCE

- Statue of Ramesses II, 1279-1212 BCE

- Ramesses II Inscription, 1279-1212 BCE

- Mummy of Ramesses II, 1279-1212 BCE

- Dream Interpretation Manual, c. 1275 BCE

- Beit el-Wali

- Ozymandias

- Leather Scroll- Quota for Brick-making, 1274 BCE

- The Battle of Kadesh at the Ramesseum, 1274 BCE

- Stela of Ramesses II, 1261 BCE

- Ramesses the Great and the Hittite Treaty, 1258 BCE

- Papyrus Harris, late 13th-early 12th century BCE

- The Wisdom of Amenemope, 1250 BCE

- The Lakhish Ewer, c. 1220 BCE

- Stelae and Reliefs of Pharaoh Merneptah, c. 1207 BCE

- Mummy of Merneptah, 1213 – 1203 BCE

- Papyrus Anastasi I, c. 1200 BCE

- Papyrus Anastasi III, c. 1200 BCE

- Papyrus Anastasi V, c. 1200 BCE

- Jar Handle, 13th century BCE

- Bronze Statue of Caananite Ruler, 13th century BCE

- Archives of Ashour Adein, 13th century BCE

- Beit Shemesh Hoard, 13th century BCE

- Canaanite Ivory Knife Handle, 13th or 12th century BCE

- Bronze Scepters and Incense Burner, 13th or 12th century BCE

- Mt. Ebal Altar, 13th-12th century BCE

- Epithet of El, late Iron Age

- Hittite Figure

Images

Articles

- Hittites in the Bible: What Does Archaeology Say? Aharon Kempinski, Biblical Archaeology Society (5:5), Sep/Oct 1979.

- Red Sea or Reed Sea? Bernard F. Batto, Biblical Archaeology Review (10:4), Jul/Aug 1984.

- Redating the Exodus, John J. Bimson and David Livingston, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:5), Sep/Oct 1987.

- Ancient Records and the Exodus Plagues, Robert R. Stieglitz, Biblical Archaeology Review (13:6), Nov/Dec 1987.

- The Route Through Sinai, Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, Biblical Archaeology Review (14:3), May/Jun 1988.

- Pomegranate Scepters and Incense Stand with Pomegranates Found in Priest’s Grave, Michal Artzy, Biblical Archaeology Review (16:1), Jan/Feb 1990.

- 3,200-Year-Old Picture of Israelites Found in Egypt, Frank J. Yurco, Biblical Archaeology Review (16:5), Sep/Oct 1990.

- Scholars Disagree: Can You Name the Panel with the Israelites? Anson F. Rainey, Biblical Archaeology Review (17:6), Nov/Dec 1991.

- Power to the Powerless—A Long-Lost Song of Miriam, George J. Brooke, Biblical Archaeology Review (20:3), May/Jun 1994.

- Exodus Itinerary Confirmed by Egyptian Evidence, Charles R. Krahmalkov, Biblical Archaeology Review (20:5), Sep/Oct 1994.

- BARlines- Huge Tomb in Egypt May Hold Pharaoh’s Firstborn, Carol Arenberg, Biblical Archaeology Review (21:4), Jul/Aug 1995.

- First Person: A Name in Search of a Story, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review (24:1), Jan/Feb 1998.

- Let My People Go and Go and Go and Go, Abraham Malamat, Biblical Archaeology Review (24:1), Jan/Feb 1998.

- The Egyptianizing of Canaan, Carolyn R. Higginbotham, Biblical Archaeology Review (24:3), May/Jun 1998.

- Cultural Crossroads, Trude Dothan, Biblical Archaeology Review (24:5), Sep/Oct 1998.

- Strata: A Lot More than Oranges, Judith Sudilovsky, Biblical Archaeology Review (26:2), Mar/Apr 2000.

- How Reliable Is Exodus? Alan R. Millard, Biblical Archaeology Review (26:4), Jul/Aug 2000.

- Contrasting Insights of Biblical Giants, Biblical Archaeology Review (30:4), Jul/Aug 2004.

- A People Is Born, Rina Abrams, COJS.

- Derechef Ramses II, National Museum News, Spring 2007.

- Rembrandt’s Great Jewish Painting, Meir Soloveichik, Mosaic, June 10, 2016.

Maps

Videos

Websites

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website