Historical survey of the Jewish population in Palestine from the fall of the Jewish state to the beginning of Zionist pioneering

Historical survey of the Jewish population in Palestine from the fall of the Jewish state to the beginning of Zionist pioneering

CHAPTER I

UNDER THE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE RULE.

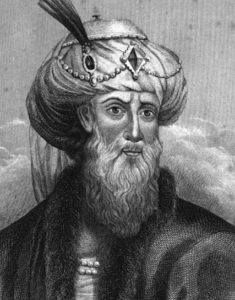

The vivid rhetoric of Josephus Flavius’ Jewish Wars and the absence of sources accessible to Western scholars for the later periods, have combined to create an impression in the minds of many people that the fatal issue of the Roman-Jewish war of 66-70 C.E. did not only result in the destruction of the Temple and of the city of Jerusalem, but brought Jewish life in Palestine to a complete standstill by obliterating what remained of the nation. However, even a cursory glance at the Jewish Wars will show that the struggle cannot have been as destructive as is popularly supposed. As shown on map A, Josephus specifically names as destroyed, apart from Jerusalem, four towns out of nearly forty, three districts (toparchies) out of eleven, and five villages. Even in these cases the destruction cannot have been very thorough. Lydda and Jaffa were burnt down by Cestius (Wars II,18,10 and 19,1), yet Jaffa had to be destroyed again (Wars III.9,3), while Lydda apparently continued to exist and surrendered quietly to Vespasian (ib. IV,18,1). The case of Bethannabris and the other villages in the Jordan Valley is even more instructive; burnt down by Placidus (Wars IV.7,5) they continued to flourish in the Talmudic period and remained Jewish strongholds down to the last days of Byzantine power in Palestine, i.e. over 500 years after their ‘destruction’. Even in Jerusalem, which underwent the misery of a long siege and piecemeal destruction, there was a revival of Jewish settlement after 70. According to the fifth century Christian author Epiphanius1 seven synagogues existed on Mount Zion, one of them still standing in the time of Constantine.

The conclusive proof of the survival of the Jews in Palestine, particularly Judaea, after 70 C.E., is furnished by the fact that another uprising, as formidable as the first, occurred barely 62 years later. The Second Roman-Jewish War, in which the Jews were led by Simon Bar-Kokhba, stands comparison with the first as regards duration (three and a half years against four), extent and destructiveness. It involved part of Galilee and the whole of Judaea, and led to a recapture of Jerusalem and the establishment of a Jewish government there; a whole Roman legion appears to have perished; and the prowess of the troops under Bar-Kokhba entirely dispelled the contempt in which the Jews had been held in the preceding century, inspiring in its place a hatred not far removed from respect.2 This time, however, the Jews paid a terrible price for their defeat in 135 C.E. The number of their dead given by Dio Cassius3 as 580,000 does not seem to be exaggerated if we consider that the greater part of Judaea was depopulated and had to be resettled. Jews were forbidden to dwell in or near Jerusalem, although even so, some Jewish villages managed to cling to the southern slope of the Judaean highlands, where their existence in the fourth century A.D. is attested by the “Onomasticon” of Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea (c. 264-c.339).4 Other villages were left in the coastal plain and the Jordan Valley, where their existence was found to be necessary to the Roman fiscus. In Galilee, however, the fundamentally Jewish character of the countryside remained unchanged even after 135 C.E., and the major part of Palestine Jewry was henceforward to be found there.

In the course of the two generations that followed the abortive attempt of Bar-Kokhba to regain Jewish independence in Palestine, the exigencies of daily life evolved a certain modus vivendi, whereby the Jewish population tacitly acquiesced in the renunciation for the time being of its attempts to gain political independence by the use of force. The Roman conquerors recognised this, first de facto, and later de jure, by the creation of a certain measure of autonomy in the administration of Jewish communal affairs, under the politico-religious leadership of the Nâsî’ (Patriarch) supported by the Sanhedrin, a mixed legislative body of religious teachers and a religious High Court. The Patriarchate became hereditary in the house of Hillel, and its authority was acknowledged not only by the Jews of Palestine, but also by those in the Diaspora. In the early days the Patriarch resided in various parts of Galilee, but he finally fixed his headquarters at Tiberias. This city therefore became the capital of Palestinian Jewry, remaining so until the end of the Byzantine rule, when the Jews were again allowed to take up residence in Jerusalem. The central authority of the Patriarch and Sanhedrin was assisted by local authorities throughout the area settled by Jews. Thus the Jewish population of Palestine, recovering from the disastrous defeat of Bar- Kokhba, again became an organized community with a corporate will. In the meantime, the central Jewish authorities introduced many measures intended to strengthen their position in Palestine- they proscribed emigration and encouraged Jews living abroad to return to the country, they prohibited the export from Palestine of some of the necessities of life such as wheat, oil and wine, they defended the Jewish peasants against abuse from within and without, they forbade the breeding of sheep and goats in closely cultivated areas as detrimental to agriculture.

That these measures proved effective is shown not only by the strong current of spiritual life among Palestinian Jewry in the ensuing centuries, although these saw the completion of the Mishna a codification of Jewish law and custom based on the interpretation of the Bible) and of the Palestinian Talmud (an elaboration of the former). But there was material development as well. The above two works frequently refer to Jewish settlements in Palestine in the second to fifth centuries C.E. Such references are the more valuable because they are spontaneous and incidental. Archaeological research is in addition constantly disclosing new names and localities, settled by Jews during the period, but for one reason or another not mentioned in the written sources.