Click here to view the original article.

BAR recently published a beautifully carved ivory pomegranate with an important inscription on it.a As partially reconstructed, the engraved inscription around the neck of the pomegranate reads as follows- “Belonging to the House of Yahweh, Holy to the Priests.” Based on this reading, many scholars have concluded that the ivory pomegranate originally came from the Jerusalem Temple constructed by King Solomon.

But how was the pomegranate used? Several suggestions have been made. One is that it was the head of a small scepter. A small hole had been carefully carved into the bottom of the pomegranate, into which a thin rod can fit. On the other hand, the pomegranate is quite small—less than 2 inches high—so it has also been suggested that it may have been a finial on a throne or cultic box, or a decoration on an altar, or an ornament elsewhere in the Temple.b

BAR’s initial publication of the pomegranate included pictures of other pomegranate scepters of similar size found with their rods intact, supporting the suggestion that the pomegranate was originally part of a small scepter, probably about 10 inches long. Since then, several other pomegranate scepters have been found.c

In the past year at Tel Nami, in an excavation I direct, we found one, possibly two and maybe three pomegranate scepters. They are being published here for the first time. We are pleased that they have been chosen by BAR as this year’s Prize Find. They are now on display in the Israel Museum, in a special case designated for new finds, so please stop by to see them if you are in Jerusalem.

I must confess we were quite surprised to find such extraordinary artifacts at Tel Nami. Before we began our excavation at this small site about eight miles south of Haifa, on the Mediterranean coast, we explored the site as part of a regional study. We thought, before starting our project, that it was probably a small fishing village. The site is situated on a stretch of land between the sea on one side and what were swamps on the other. The swamps in antiquity were fed by water from the Nahal Me’arot, flowing from the Carmel mountain range. This rivulet probably formed an estuary that served as a harbor or inner anchorage system. This would be quite important for our understanding of ancient sea trade before the earliest harbors were built in open water at the end of the second millennium B.C.E.d So you can see why our expectations were quite far from religious rituals or temple practices.

The archaeological remains examined in the course of our survey and excavationse clearly revealed that the site had been settled in the first part of the second millennium B.C.E. (Middle Bronze Age II A). It was abandoned at the end of this period (MB II A) or the beginning of MB II B. It was resettled in about the 14th century B.C.E. (Late Bronze Age II A). There were at least two destructions before its final abandonment sometime around 1200 B.C.E. After that period, only army stations from late periods—Turkish, English and Israeli—were built on the peninsula.

Changes in sea levels during Nami’s ancient existence produced changes in the coast line, resulting in changed settlement patterns at the site. In 1986, under sand dunes on the coast, architectural remains from the same periods as those on the peninsula were discovered. But in the 13th century B.C.E., this same area was used as a burial ground.

It was this cemetery that yielded our unexpected finds. Here we found an ivory scepter, 7 inches long, which probably came from a robbed grave. Unfortunately, only the rod was recovered; the head is missing. The ivory rod is exquisitely decorated with incisions.

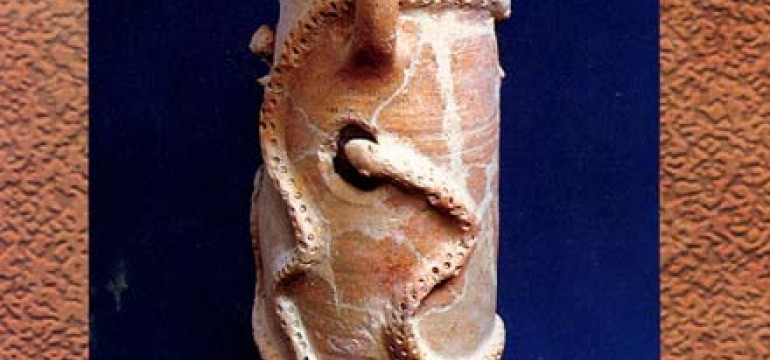

Not 15 feet from this ivory scepter rod, we discovered an unrobbed grave. There, two bronze scepters complete with heads lay on a skeleton. These scepters are about 13 inches long, nearly twice as long as the ivory scepter rod.

One of the bronze scepters is clearly topped by a pomegranate. The rod is decorated with incisions. As we excavated it, it appeared to have silver sheeting in some of the incisions. Unfortunately, this apparent sheeting disappeared when the object came into contact with the atmosphere.

The head of the second bronze scepter cannot be identified with certainty. It could be a pomegranate, or it could be a poppy seed pod. Both of these fruits were signs of bounty, because both have many seeds. As can be seen in the pictures, both of these bronze scepters were found in excellently preserved condition. They date to the 13th century B.C.E. or perhaps to the early 12th century B.C.E.

That they have a cultic significance is clear, although we are not sure precisely how they were used. One suggestion is based on the sacral reliefs depicted on the palaces at Nimrud and Khorsabad in Mesopotamia. At Nimrud, a man is depicted carrying a sacrificial animal in one hand and pomegranates in the other. At Khorsabad, a man is carrying a sacrificial kid, followed by another man carrying scepters that seem to bear the likeness of pomegranates, possibly as symbols of bounty. In short, the pomegranate scepters may have been used as part of the sacrificial rite.

In addition to the scepters already referred to, others have been found at various sites and from various periods. Two particularly beautiful ivory examples, dated to the 13th century B.C.E., come from Lachish. These were actually found in a Canaanite temple, confirming the cultic use of such scepters. Others have been found in Cyprus—just across the sea from Nami—in late second millennium contexts. Still others have been discovered in a Phoenician tomb at Achziv, north of Akko, dated to the eighth century B.C.E.

In the same grave where we found the bronze scepters at Tel Nami, we also found bronze incense burners. One of these—a four-footed stand—has three hanging “bells” attached to the top of the stand. The bells represent either pomegranates or poppy seed pods.

A few similar stands, although not of such exquisite workmanship, have been found at Ugarit (Ras Shamra),1 Beth-Shean and Megiddo (the latter in a temple).2 The stands held a bronze plate on which incense was burned, but precisely how this functioned ritually is still unknown.

One possible answer may be found on Egyptian reliefs that date to the same period as our finds at Tel Nami. In the depiction of sieges of Canaanite cities carried out by Seti I, Ramesses II, and possibly Merneptah and Ramesses III, one can discern a cultic event taking place inside the walls of the besieged Canaanite town. Men and women are shown on the uppermost level of their fort with their hands pointing toward heaven, while some children are hanging over the walls, their bodies limp. A bearded man holds an incense stand, usually burning. The stand is much like the ones found at Tel Nami. The thin middle section seems to indicate that these were indeed made of metal, probably bronze, the common metal of the period.

Who then is the bearded figure holding the bronze incense burner? Could this be the priest? What is the cultic event taking place on top of these besieged walls in which these burners played such an important role? Is it possible that these people are involved in child sacrifice?3 The besieged city was in imminent danger of destruction the mighty Egyptian army was at its gates. Almost all was lost. Could the Canaanite gods hear the desperate cries of their people with such an offering and with the sweet smell of incense entering their divine nostrils?

Attestations to such child sacrifice do exist. King Mesha of Moab did just that—sacrificed his son—as a last resort when besieged by the Israelites (2 Kings 3-27).f There is no clear description of this practice among the Israelites, although it is mentioned several times in the Bible, especially in relationship to the god Moloch4 (Isaiah 30-33; Genesis 22-1–19; Exodus 22-29; Judges 11-29–40).

The practice of child sacrifice in dire need is not peculiar to the Semites. When the Greek navy under Agamemnon could not depart for battle because of high winds, Agamemnon, in a desperate attempt to calm the seas, sacrificed his daughter, Iphigenia.5 The Greeks were not besieged by humans, but rather by their gods, but the propitiation was the same.

Child sacrifice continued later in the first millennium B.C.E. In some cases, various animals such as a ram or a heifer were substituted for the child. Even Iphigenia, in later stories, was saved at the last minute by the goddess Artemis, who exchanged a hind or a bear for the young girl.

Perhaps it is premature to suggest child sacrifice at Tel Nami, but it does seem clear that the pomegranate scepters and the bronze incense stands were used in some religious ritual. I suspect that the skeleton on which we found these implements is the mortal remains of a priest and that the tomb deposits represent cultic implements used by him in the performance of his office. Incidentally, a pair of gold earrings in the form of pomegranate blossoms were also found in the same grave, accentuating the importance of the pomegranate to the cult represented in the grave.

Just a few months ago, we discovered at Tel Nami a temple perched on top of the peninsula, about 300 feet from the cemetery. Perhaps, when we have fully excavated the temple, we will know more about the religious rites of the ancient peoples who lived here in what must have been an important international port in the second millennium B.C.E.

a. André Lemaire, “Probable Head of Priestly Scepter From Solomon’s Temple Surfaces in Jerusalem,” BAR 10-01; see also Hershel Shanks, “Was BAR an Accessory to Highway Robbery?” BAR 14-06; Shanks, “Pomegranate, Sole Relic From Solomon’s Temple, Smuggled Our of Israel, Now Recovered,” Moment, December 1988; Nahman Avigad, “The Inscribed Pomegranate from the ‘House of the Lord,’” Israel Museum Journal 8 (1989), p. 7.

b. See “Pomegranate ‘Priceless’ Says Harvard’s Frank Cross,” BAR 10-01.

c. Avigad, “The Inscribed Pomegranate,” p. 13.

d. B.C.E. (Before the Common Era) is the religiously neutral term used by scholars, corresponding to B.C.

e. We were assisted by archaeologists and volunteers from the University of Haifa, Denmark, Italy and the United States (Univ. of Mass. at Amherst and the Program of Nautical Archaeology, Texas A & M). Mr. and Mrs. Robert Shay of Philadelphia and Prof. Daniel Hillel made major donations.

f. See Baruch Margalit, “Why King Mesha of Moab Sacrificed His Oldest Son,” BAR 12-06.

1. Claude F-A. Schaeffer, Enkomi-Alasia, Paris, 952.

2. H. W. Catling, Cypriot Bronzework in the Mycenaean World (Oxford Clarendon Press, 964).

3. See Baruch Margalit, “Why King Mesha of Moab Sacrificed His Oldest Son,” BAR 12-06. See also A. Spalinger, “A Canaanite Ritual Found in Egyptian Reliefs,” Journal of the Society of the Study of Egyptian Archaeology 8 (1978), pp. 47–60.

4. Roland de Vaux, Ancient Israel, vol. 2 (New York McGraw Hill, 1961). But see Lawrence E. Stager and Samuel R. Wolff, “Child Sacrifice at Carthage—Religious Rite or Population Control?” BAR 10-01.

5. Aeschylus, The Agamemnon.