Shortly after 538 B.C.E. the Davidic scion Sheshbazzar set out from Babylon at the head of a group of returning Judeans and soon arrived in the Land of Israel. He apparently had the title pehah, governor, as did his successor, Zerubbabel. Sheshbazzar must have immediately taken steps to begin rebuilding the Temple, but the Bible credits

Shortly after 538 B.C.E. the Davidic scion Sheshbazzar set out from Babylon at the head of a group of returning Judeans and soon arrived in the Land of Israel. He apparently had the title pehah, governor, as did his successor, Zerubbabel. Sheshbazzar must have immediately taken steps to begin rebuilding the Temple, but the Bible credits

Zerubbabel with its completion (Ezra 3-6–11). With the rebuilding of the Temple came the restoration of the sacrificial ritual.

The early years of the Second Commonwealth were difficult ones. Judea was actually no more than a small area around Jerusalem, and by 522 B.C.E. its population must have numbered less than twenty thousand. The holy city itself was in ruins and scarcely inhabited. The Samaritans to the north, a mixed people made up of remnants of the populace of the destroyed northern kingdom of Israel and various groups brought in by the Assyrians, were openly hostile. Many Judeans were so preoccupied with eking out a living that they took little interest in the rebuilding of the Temple. The situation deteriorated to the point that work on the Temple had to cease temporarily.

At about this time, Zerubbabel, the nephew of Sheshbazzar, succeeded to the governorship. Zerubbabel was the son of Shealtiel son of Jehoiachin, a scion of the royal family of Judah. Sometime between 538 and 522 B.C.E. Zerubbabel had arrived in Jerusalem at the head of a group of returning exiles. The high priesthood was reconstituted under the Zadokite high priest Joshua ben Jehozadak. Nevertheless, eighteen years after the start of construction, the Temple had still not been completed. The political circumstances leading to the ascension of Darius I (522–486 B.C.E.) to the throne of the Persian Empire aroused messianic expectations among the Jews of Judea, as shown in the books of Haggai and Zechariah, both composed around 520 B.C.E. These two prophets agitated for the completion of the Temple and the restoration of the pure worship of the God of Israel to the exclusion of all syncretistic practices. The leaders of Judea understood the importance of the Temple, and within four years it was finished. The work of building the Temple was apparently carried on despite efforts by the Samaritans to depict it as a messianic ploy aimed at reestablishing Judean independence under a Davidic king.

In March of 515 B.C.E. the Temple was completed amidst great rejoicing. Sacrifices and prayers for the king of Persia were offered. Judea now had its national and religious center. The future of the Jewish people in its ancestral land was assured for the foreseeable future. God could be properly worshipped in accord with the ancient traditions. There is some reason for thinking that the messianic agitation surrounding the person of Zerubbabel led the Persian authorities either to remove him from office or to not reappoint him when his term ended. In any case, from now until the time of Nehemiah (mid-5th century B.C.E.) the high priests ruled. Judea seems for a time to have been only a small theocratically ruled political unit within the larger province of Samaria. This state of affairs lasted for about seventy years after the completion of the Second Temple. In the early years of this period, the Persian Empire attained its high point under Darius I. The little we know of the situation in Judea indicates that only limited progress was made toward repopulating it. Most of the empire’s Jews remained in the Diaspora. The sparse evidence tells us that Jews were settled, for example, in Babylonia itself, in Sardis (in Asia Minor), and in Lower (northern) Egypt.

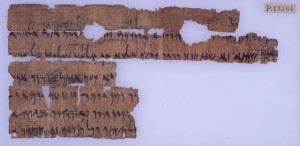

At the same time, Jews flourished in Elephantine in Upper (southern) Egypt throughout the fifth century B.C.E. There they were established in a military colony entrusted by the Persian Empire with the defense of its interests. Many Aramaic documents have survived from Elephantine, and these provide us with a window into the colony’s culture and religion. The Elephantine Jews, in a temple of their own, practiced a syncretistic form of worship not unlike that of First Temple times, mixing pagan elements with the religion of the God of Israel.

By the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the population of Judea had probably doubled, and additional groups of exiles had returned. Some Jews now lived in more northerly parts of the country, in the territory of the erstwhile Kingdom of Israel. While the high priests controlled internal affairs, other matters rested in the hands of the governors of the province of Samaria who, according to the biblical account, were not above accusing the Jews of sedition when it was advantageous to them. Because of difficulties with their neighbors, the security of Judea deteriorated, and sometimes during the reign of Artaxerxes I (465/64–424 B.C.E.) the rebuilding of the fortifications of Jerusalem was begun. The aristocracy of Samaria, with the help of an order from the king, was able to stop this project temporarily.

Monotheistic worship was certainly the norm in Judea. The books of Malachi and Nehemiah, however, speak of such problems as violations of sacrificial law, neglect of the Sabbath, and nonpayment of tithes. There was a breakdown of morality and a rise in divorce. Cheating of employees and preying on the weak became commonplace, and many of the poor were reduced to servitude. Intermarriage with the surrounding nations threatened the continuity of the Jewish community.

It was at this crucial juncture that the great reformers Ezra and Nehemiah made their appearance. Fortuitously, this was also a period of great instability in the Persian Empire. In an effort to shore up his lines of communication with Egypt, Artaxerxes wanted to regularize the situation in Palestine, and this provided Ezra and Nehemiah with the opportunity to make substantial progress.

The chronological relationship of the careers of these two great leaders poses serious difficulties. Nehemiah’s career extended from 445 until sometime after 433 B.C.E. Ezra’s dating is more difficult. The plain sense of the biblical text suggests that he arrived in Judea in 458 B.C.E. (thirteen years before Nehemiah) and completed his work shortly after Nehemiah’s arrival. Some scholars take the view that he arrived long after Nehemiah’s work had ended. A final approach, following the Greek text of the apocryphal 1 Esdras, suggests that Ezra arrived shortly before the end of Nehemiah’s career in about 428 B.C.E.

According to the biblical account, which we see no compelling reason to set aside, Ezra left Babylon in 458 B.C.E. at the head of a considerable company of returnees. After a four-month journey, unaccompanied by a military escort, the caravan arrived in Jerusalem. Ezra came armed with a copy of the Torah and a document from the king authorizing him to enforce it. He was to teach the law and to set up the necessary administrative apparatus to see that it was followed. He had also obtained permission to collect contributions from the Jews of Babylonia to support the Temple in Jerusalem. Ezra is described by the Bible as “a scribe of the law of the God of Heaven.” He was of priestly lineage and was probably appointed at the request of influential Jews at the Persian court. Those who see Ezra as coming after Nehemiah maintain that Nehemiah was responsible for his appointment. While it might seem unlikely that the monarchs of Persia would be concerned with the religious observances of the Jews of Judea, Ezra’s mission can be understood from the standpoint of purely Persian interests. Under Persian rule, each subject people was allowed to live by its ancestral laws, which were enforced by the imperial government. Violations of the laws of the group to which one belonged constituted an offense against the state precisely because they led to instability. The maintenance of order in Judea, for example, would ensure the security of the land bridge to Egypt, and therefore the king required, in his own interest, that Jewish law be observed.

Immediately preceding the feast of Sukkot (Tabernacles) soon after his arrival, Ezra read the Torah publicly to the entire people. Indeed, this was a covenant-renewal ceremony in the strict sense. To make the Torah understandable to them, he had it explained. By this time, Aramaic, a West Semitic language, had become the spoken language of much of the Persian Empire and was the vernacular of most Jews. The biblical account relates that the people were greatly saddened when they learned that they had been lax in following the law, and it was only with difficulty that Ezra was able to restore the joy of the festival season. Throughout the festival the law was read on each day.

Nonetheless, Ezra continued to face violations of the Torah’s regulations. Mixed marriages were a substantial problem. Their increase must have resulted from the small size of the Judean population and the attendant difficulty in finding spouses. Ezra led the people to enter into a covenant by which they voluntarily expelled the 113 foreign wives in the community. Already in this period the law that Jewish identity is determined through the mother was operative. The biblical narrative singles out the families in which the mother was not Jewish, for such unions led to the birth of non-Jewish children. Despite Ezra’s considerable efforts, however, we can be sure that intermarriage continued, although on a much smaller scale.

The high point of Ezra’s career was certainly the covenant renewal and reformation of Jewish life recorded at the end of the Book of Nehemiah (chaps. 9 and 10). The covenant he instituted bound the people to abstain from mixed marriages, refrain from work on the Sabbath, observe the laws of the sabbatical year, pay taxes for the communal maintenance of the Temple, and provide wood offerings for the sacrificial altar, first fruits, and tithes. A careful examination of the covenant, and of Ezra’s decision to expel foreign wives, shows strong influence of the midrashic method of biblical interpretation, a matter to which we will return below. Those who date Ezra’s arrival to the second term of Nehemiah see the covenant as the culmination of the joint efforts of the two men, but the biblical sources do not place them together.

Ezra now fades from the scene. He is often credited with having created postbiblical Judaism, a view somewhat overstated. What this leader, teacher, and scholar did was to establish the basis for the future of Judaism- from here on, the canonized Torah, the Five Books of Moses, would be the constitution of Jewish life. By pointing postbiblical Judaism on the road of scriptural interpretation, Ezra had ensured the continuity of the biblical heritage.

In December of 445 B.C.E. Nehemiah, the cupbearer to King Artaxerxes, was informed by his brother Hanani, who had just arrived from Jerusalem, of the difficult situation in Judea. Nehemiah approached the king and succeeded in getting permission to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem, obtaining the governorship of Judea and having it established as a province separate from Samaria. By 444 B.C.E. he had established his control over the newly created province. In a fifty-two-day stretch he managed to rebuild the city walls, although it is possible that this was a temporary fortification and that the permanent walls took another two years to complete.

Throughout the period of rebuilding, Sanballat, the governor of Samaria, aided by Tobiah, the ruler of Ammon, and Gashmu, an Arab chieftain, constantly opposed Nehemiah. Nonetheless, Nehemiah persevered. In order to create a commercial center for the country, he brought people from the hinterland into Jerusalem. With the walls up and the new population base established, Jerusalem’s role as the center of Jewish life in Palestine was guaranteed.

In Nehemiah’s time the population of Judea may be estimated at some fifty thousand souls, concentrated on the mountain ridge stretching from Beth Zur north to Bethel. The province had already been divided into districts when he came into office, probably remnants of the administrative system set up by the neo-Babylonian rulers after the conquest and destruction of Judah in 586 B.C.E. He allied himself with those who wanted to restore pure monotheism while his aristocratic opponents continued the old syncretistic tendencies against which the prophets had constantly railed.

After twelve years, Nehemiah’s term as governor came to an end. Soon after returning to the Persian court, he was reappointed to the post. Nehemiah returned to Judea to find that conditions had worsened. The syncretistic party had scored substantial gains, and he had to expel Tobiah the Ammonite from an office in the Temple. Indeed, a descendant of the high priest Eliashiv had married the daughter of the Samaritan Sanballat. Nehemiah began a vigorous religious reform, fighting against the rising tide of intermarriage, and insisting that levitical tithes be paid and that wood for the altar be properly furnished. He strengthened and encouraged the strict observance of the Sabbath.

Those who take the view that Ezra came after Nehemiah see him as arriving at this time, perhaps having been brought by Nehemiah to help restore the proper observance of the Torah. We do not know exactly when Nehemiah’s second term ended. It may have been with the death of Artaxerxes I in 424 B.C.E. He was definitely out of office by 408 B.C.E., when a Persian named Bagoas was governor of Judea according to the Elephantine documents.

The end of the fifth century and most of the fourth are represented by only scanty historical material. An Elephantine papyrus speaks of a Hananiah who governed Judea in 419 B.C.E. He may have been the same person as Hanani, the brother of Nehemiah, who had informed him about the difficulties confronting the Judean community. Josephus relates that the high priest at this time, one Yohanan, had a quarrel with his brother Joshua, who was plotting against him, and murdered him in the Temple. As a result, the shocked and dismayed Bagoas imposed severe restrictions on the Jews.

Considerably more information is available about the Jews of Elephantine during this period. We know that the syncretistic Jews of this colony attempted to celebrate Passover in accord with the law. In 410 B.C.E. the Jewish temple at Elephantine was destroyed in a riot incited by the priests of the local god Khnum with the help of the Persian commander. The Jews had trouble getting their temple rebuilt, perhaps because of the native Egyptian distaste for animal sacrifice. Attempts to enlist the help of Yohanan, the high priest mentioned in the preceding paragraph, failed because the laws in Deuteronomy make it clear that there was to be no sacrifice outside of God’s chosen place, taken to be Jerusalem. In 408 B.C.E. the colonists of Elephantine wrote for help to Bagoas, the governor of Judea, and to Delaiah and Shelemiah, the sons of Sanballat, the governor of Samaria. Following the advice of Delaiah and Bagoas, they then petitioned the Persian satrap (provincial governor), who allowed them to rebuild the temple around 402 B.C.E. after they had voluntarily discontinued animal sacrifices and the attendant

offerings.

The first two-thirds of the fourth century were a period of persistent decline in the Persian Empire at large. Of the Jewish communities, whether in Palestine or outside, virtually nothing is known. In all probability the building of the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim commenced in the last years of the Persian period. Silver coins of the Attic drachma type were minted by the semi-autonomous commonwealth of Judea (Yahud). Seal impressions on jar handles indicate that the vessels were used for the collection of taxes in kind. The inscriptions specify the name of the official to whom the tax was paid. Some evidence suggests that the high priest was the chief administrator of

the country.

As the Persian period drew to a close, the signs of Greek influence on the material culture of Palestine steadily increased. Greek mercenaries, traders, and scholars were visiting the country in ever larger numbers, making a distinctive mark on its character. Thus the dawning of the Hellenistic period, which we will discuss in chapter 4, came as the completion of a cultural process long under way.