Excerpted from Lawrence H. Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991.

Excerpted from Lawrence H. Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991.

It is against the background just sketched that the phenomenon of religious sectarianism came to fruition. There had been divergences in Israelite religion even in the biblical period, and in many cases the very same issues that had led to conflicts in biblical times became the basis for disagreements and strife in the Hasmonean period. Yet the nature of the sectarianism of which we are speaking is very different. In biblical times, the fundamental question was whether the God of Israel was to be worshipped exclusively, or whether a syncretistic identification of Him with Canaanite gods and cult was to take place. To the Judeans, the same point was at stake in their rejection of the Samaritans and the subsequent schism. It had resurfaced earlier in the Hellenistic period, in the years leading up to the Hellenistic reform and the persecutions of Antiochus IV. The nation had rallied behind the Maccabees precisely because, like the biblical prophets and the deuteronomic editors of the historical books of the Bible, they would not tolerate any tinkering with the exclusive monotheism to which they adhered.

Now, however, the debates would all take place within a new context. Matters would revolve around two axes. First, while it was now accepted without question that the canonized Torah was authoritative, there were many differences of opinion as to its interpretation. Second, while extreme Hellenism had been rejected, the exact parameters of assimilation or Hellenization and of separatism and pietism were still to be determined. Ultimately, these questions would be resolved only after the destruction of the Temple with the rise of Rabbinic Judaism. For the present they would be played out, not in the ivory tower of religious disputation, but in the political, social, and even economic affairs of the Hasmonean period.

Our sources suggest that the Hasmonean priest-kings relied on a body of advisors or councilors called the Gerousia. This body was composed of a shaky coalition of Pharisees and Sadducees, the two groups which were most active in the political life of the state. Like the other groups to be described here, they also had distinct religious ideologies, as

well as social characteristics.

The Pharisees

The Pharisees derived their name from the Hebrew perushim, “separate.” This designation most probably refers to their separation from ritually impure food and from the tables of the common people, later termed the ‘am ha-‘ares (“people of the land”) in rabbinic sources, who were not scrupulous regarding the laws of levitical purity and tithes. The term may originally have been a negative designation used by the opponents of the Pharisees. Tannaitic sources describe those who observed the laws of purity as haverim, “associates,” and groups of such people as havurot. The haverim are contrasted with the ‘am ha-‘ares. Although most historians assume these groups to have been Pharisaic, the sources never associate the terms “Pharisee” and haver. In rabbinic sources, the Pharisees are sometimes designated as “the sages,” an anachronism resulting from the view of the rabbis that they were the continuators of the Pharisaic tradition. Although the influence of the Pharisees grew steadily until they came to dominate the

religious life of the Jewish people, they are said to have numbered only six thousand in Herodian times.

By and large, the Pharisees had three major characteristics. First, they represented primarily the middle and lower classes. Second, and perhaps as a consequence of their social status, they were really not Hellenized and seem to have remained primarily Near Eastern in culture. To be sure, they may have adopted certain Greek words or intellectual approaches, but they viewed as authoritative only what they regarded as the ancient traditions of Israel. Third, they accepted what they termed the tradition of the fathers,” nonbiblical laws and customs said to have been passed down through the generations. These teachings supplemented the written Torah and were a part of what the rabbis would later call the oral law. They are said to have been extremely scrupulous in observing the law and to have been expert in its interpretation.

In a number of significant teachings the Pharisees appear to have espoused views that were later incorporated in the rabbinic tradition. The Pharisees accepted the notions of the immortality of the soul and of reward and punishment after death, both of which the Sadducees denied. The Pharisees are said to have believed in angels, another belief which the Sadducees denied. The Pharisees accepted the idea of divine providence, believing that God allowed human beings free will but could play a role in human affairs. The Sadducees rejected totally the notion of divine interference in the affairs of man. To them free will was complete and inviolable. In contrast, the Essenes maintained a belief in absolute predestination, as did the sect of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Although these views are recounted in Greek philosophical garb by Josephus, our only source for the theological disputes between the two groups, the actual points of view emerge from varying interpretations of the biblical tradition, and, therefore, the basic outlines of the controversy may be accepted as authentic.

From the accounts available to us, it appears that the Pharisees were divided over one of the most burning issues of the period. Some advocated an accommodationist policy toward the government, so long as it allowed them to practice Jewish traditions in the manner required by the Pharisaic view. Others maintained that no government was acceptable, whether controlled by non-Jews or by nonobservant Jews, so long as it was not built on the Pharisaic notion of Torah observance, and they called upon their compatriots to rise in revolt. This dispute can be traced throughout the history of Pharisaism and continued in Rabbinic Judaism, becoming central in the two Jewish

revolts against Rome.

In the extant sources, the Pharisees first appear by name during the reign of Jonathan, brother of Judah the Maccabee (ca. 150 B.C.E.). Many scholars have attempted to identify the Pharisees with, or to locate their origins in, the Hasidim who were allies of Judah in the Maccabean Revolt. This theory, however, cannot be substantiated. Further, our knowledge of the Hasidim is very limited. It is probable that they were not really a sect or a party, but rather a loose association of pietists, as denoted by this term in later talmudic literature.

Rabbinic sources trace the Pharisees back to the Men of the Great Assembly, who are said to have provided Israel’s religious leadership in the Persian and early Hellenistic periods. Some modern scholars have associated the Soferim (“Scribes”) with the Men of the Great Assembly. The Soferim would then be forerunners of the Pharisaic movement. Unfortunately, the historical evidence does not allow any definite conclusions here. All that can be said is that the Pharisees could not have emerged suddenly, full-blown, in the Hasmonean period. Their theology and organization must have been in formation somewhat earlier. How much earlier and in what form, we cannot say.

In any case, the Pharisees appear in Hasmonean times as part of the Gerousia in coalition with the Sadducees and other elements of society. Here they sought to advance their vision of the way the Jewish people should live and govern themselves. Under John Hyrcanus and Alexander Janneus, conditions led them further and further into the political arena. As the Hasmoneans became increasingly Hellenized, the Pharisees expressed greater opposition to them. Under John Hyrcanus, there was a decisive Hasmonean tilt toward the Sadducees. In the time of Alexander Janneus the Pharisees were in open warfare with the king, who was consequently defeated by the Seleucid Demetrius III Eukairos (96–88 B.C. E.) in 89 B.C.E. This rout led to a reconciliation between the king and the Pharisees. During the reign of Salome Alexandra they were the dominant element, in control of the affairs of the nation, although the extent of their influence has been exaggerated by many scholars.

There has been considerable controversy regarding the extent to which the later rabbinic claims that the Pharisees dominated the ritual of the Jerusalem Temple ought to be taken at face value. Recently, the trend has been to discount these reports as a later reshaping of history in light of post-destruction reality. Sources soon to be published from the Dead Sea Scrolls now require reevaluation of the entire question. These texts indicate that the views assigned to the Pharisees in a number of mishnaic disputes are precisely those which were in practice in the Jerusalem Temple. Whether the dominance of the Pharisaic view was due to the political power of the Pharisees, or whether their positions were indeed commonly held views in the Hasmonean period, cannot be determined with certainty.

Over and over Josephus stresses the popularity of the Pharisees among the people. This must certainly have been the case in the last years of the Second Temple period, for which Josephus had first-hand experience, although his pro-Pharisaic prejudices must be acknowledged. Their popularity, together with the unique approach to Jewish law which they espoused, laid the groundwork for the eventual ascendancy of the Pharisees in Jewish political and religious life. The oral law concept which grew from the Pharisaic “tradition of the fathers” provided Judaism with the ability to adapt to the new and varied circumstances it would face in ta1mudic times and later. As such, Pharisaism would become Rabbinic Judaism, the basis for all subsequent Jewish life and civilization.

The Sadducees

The Sadducees also were a recognizable group by about 150 B.C.E. They were a predominantly aristocratic group. Most of them, in fact, were apparently priests or those who had intermarried with the high priestly families. They tended to be moderate Hellenizers whose primary loyalty was to the religion of Israel but whose culture was greatly influenced by the environment in which they lived. The Sadducees derived their name from that of Zadok, the high priest of the Jerusalem Temple in the time of Solomon. The Zadokite family of high priests had served at the head of the priesthood throughout First Temple times, except when foreign worship was brought into the Temple, and during Second Temple times until the Hasmoneans took control of the high priesthood. Ezekiel 44-9–16 had assigned the priestly duties exclusively to this clan.

The Sadducees rejected the “tradition of the fathers” which the Pharisees considered as law. For this reason the later rabbinic sources picture them as rejecting the oral law. The notion of some church fathers that the Sadducees accepted only the Torah as authoritative, rejecting the Prophets and the emerging corpus of Writings, is unsubstantiated by any earlier sources.

It is difficult to date the many differences which tannaitic texts ascribe to the Pharisees and Sadducees. Some of these are preserved only in very late post-talmudic sources, but those in the mishnaic materials are of greater interest. The Sadducees required compensation for injuries done by a person’s servant, whereas the Pharisees required it only in the case of one’s animals, according to their interpretation of Exod. 21-32, 35–36. The Sadducees required that false witnesses be executed only when the accused had already been put to death because of their testimony (Deut. 19-19–21). The Pharisees imposed this penalty only when the accused had not been executed. The Sadducees criticized the inconsistencies in the Pharisaic interpretations of the purity laws, and the Pharisees regarded Sadducean women as menstrually impure as a result of following improper interpretations of these laws. In general, the Sadducees saw the purity laws as referring to the Temple and its priests, and saw no reason for extending them into the daily life of all Israel, a basic pillar of the Pharisaic approach.

A fundamental question is why the Sadducees disagreed so extensively with the Pharisaic tradition and, therefore, how they came to disagree on so many matters of Jewish law. Later Jewish tradition sought to claim that all the differences revolved around the Sadducean rejection of the oral law. Based on this assumption, modern scholars have argued that the Sadducees were strict literalists who followed the plain meaning of the words of the Torah. Yet such an approach would not explain most of the views on legal matters that were attributed to the Sadducees.

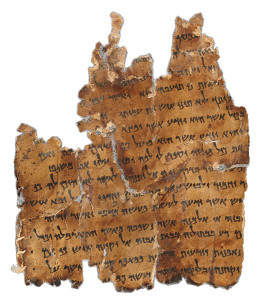

Recent discoveries from the Dead Sea caves have aided greatly in this respect. One text, written in the form of a letter purporting to be from the founders of the Dead Sea sect, who were apparently closely related to the Sadducees, to the leaders of the Jerusalem establishment, lists some twenty-two areas of legal disagreement. Comparison of these with the Pharisee-Sadducee disputes recorded in rabbinic literature has led to the conclusion that the writers of this letter took the views attributed to the Sadducees while their opponents in the Jerusalem priestly establishment held the views attributed later to the Pharisees. Examination of this document and related materials leads to the conclusion that Sadducees had their own methods of biblical exegesis and accordingly derived laws which were different from those of the Pharisees and their supporters.

The Sadducees also differed with the Pharisees on theological questions. As already mentioned, they denied the notion of reward and punishment after death as well as the immortality of the soul, ideas accepted by the Pharisees. They did not believe in angels in the supernatural sense, although they must have acknowledged the many divine “messengers” mentioned in the Bible. To them, since man had absolute free will, God did not exercise control over the affairs of mankind.

The Sadducean party cannot be said to have come into being at any particular point. The priestly aristocracy, which traced its roots to First Temple times, had increased greatly in power in the Persian and Hellenistic periods, since the temporal as well as the spiritual rule of the nation was in its hands. Some priests had been involved in the extreme Hellenization leading up to the Maccabean revolt, but most of the Sadducean lower clergy had remained loyal to the Torah and the ancestral way of life.

In the aftermath of the revolt, a small and devoted group of Sadducean priests probably formed the body that eventually became the Dead Sea sect. They were unwilling to tolerate the replacement of the Zadokite high priest with a Hasmonean which took place in 152 B.C.E. Further, they disagreed with the Jerusalem priesthood on many points of Jewish law. Recent research indicates that soon after the Hasmonean takeover of the high priesthood, this group repaired to Qumran on the shore of the Dead Sea. (The complex question of the identification of the Qumran sect is taken up below.) Other moderately Hellenized Sadducees remained in Jerusalem, and it was they who were termed Sadducees, in the strict sense of the word, by Josephus in his descriptions of the Hasmonean period and by the later rabbinic traditions. They continued to be a key element in the Hasmonean aristocracy, supporting the priest-kings and joining with the Pharisees in the Gerousia. After dominating this body for most of the reign of John Hyrcanus and that of Alexander Janneus, they suffered a major political setback when Salome Alexandra turned so thoroughly to the Pharisees. Thereafter the Sadducees regained power in the Herodian era, when they made common cause with the Herodian dynasty. In the end, it was a group of Sadducean lower priests, by deciding to end the daily sacrifice for the Roman emperor, who took the step that set off the full-scale revolt against Rome in 66 C.E.

Closely allied to the Sadducees were the Boethusians, who seem to have held views similar to those of the Sadducees. Most scholars ascribe the origin of the Boethusians to Simeon ben Boethus, appointed high priest by Herod in 24 B.C.E. so that he would have sufficient status for Herod to marry his daughter Mariamme (II). This theory is completely unproven, and certain parallels between Boethusian rulings and material in the Dead Sea Scrolls argue for a considerably earlier date. There certainly were some differences between the Sadducees and the Boethusians, but the latter appear to have been a subgroup or an offshoot of the Sadducean group.

The most central of the disputes recorded in rabbinic literature as having separated the Boethusians from the Pharisees pertained to the calendar. The Boethusians held that the first offering of the Omer (barley sheaf, see Lev. 23-9–14) had to take place on a Sunday rather than on the second day of Passover, in accord with Lev. 23-11, “on the morrow of the Sabbath.” To ensure that this festival be observed on the proper day of the week, a calendar was adopted which, like the one known from the Dead Sea sect and the pseudepigraphical Book of Jubilees, was based on both solar months and solar years. Following this calendar, the holiday of Shavuot (Pentecost) would always fall on a Sunday. While this approach seemed to accord better with the literal interpretation of the words “on the morrow of the Sabbath,” the Pharisees could accept neither the innovative solar calendar (the biblical calendar was based on lunar months) nor the interpretation on which it was based. To them, “Sabbath” here meant festival. (The attribution of this Boethusian view to the Sadducees by some scholars results from confusion in the manuscripts of rabbinic texts.)

The Sadducean approach certainly had a major impact on political and religious developments in the Judaism of the Second Temple period. Sadducean offshoots played a leading role in the formation of the Dead Sea sect, which will be discussed below. There is evidence that some Sadducean traditions remained in circulation long enough to influence the Karaite sect, which came to the fore in the eighth century C.E. Yet otherwise, with the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., the Sadducees ceased to be a factor in Jewish history. The sacrificial system, in which they had played so leading a role, was no longer practiced. Their power base, the Jerusalem Temple, was gone, and their strict constructionism augured poorly for the adaptation of Judaism to the new surroundings and circumstances of the years ahead.