Overview- Jewish Responses to Spiritual Challenges

Meeting material challenges in a rapidly changing environment constituted the first priority for the Jews of medieval western Christendom, one they accomplished by and large effectively. At the same time, these Jews encountered major challenges in the cultural and spiritual spheres, again in a rapidly changing and creative majority ambiance. For the Jews of medieval western Christendom, the intellectual and spiritual threats were every bit as significant as the material. Maintenance of Jewish identity in the face of ongoing majority pressures toward conversion hinged on establishment of a creative Jewish minority culture that could comfortably compete with majority achievement. Medieval Jewish polemical denigration of Christian majority culture should not obscure Jewish awareness of the vitality of medieval Christian civilization. It must be remembered that this vitality convinced Jews to remain in their home territories when these passed into Christian hands and—more strikingly—to migrate into Christian lands, some entirely new to Jewish settlement.

Jewish cultural and religious creativity in medieval western Christendom was stimulated from two directions. The first of these sources of stimulation was internal. The needs of Jewish life and the dynamic of Jewish religious obligation required ongoing engagement with the rich legacy of the past. That legacy had to revisited and adapted to ever-evolving circumstances. At the same time, Jewish communities over the ages have benefited from the stimulation of surrounding societies. Despite the negative impressions fostered by the Renaissance and the Enlightenment and by Jewish polemical devaluation, medieval European society was richly creative in a wide range of cultural domains, and the Jewish minority was stimulated by this majority creativity.

While such external stimulation is a constant of Jewish experience, in medieval western Christendom external stimulation took an unusually intense form. The Christian majority was—as already noted—aggressive and deeply committed to ongoing missionizing among the Jewish minority. This majority aggressiveness created special stresses for the Jews of Europe. While Jews readily acknowledged the greater numbers and material power of Christian society, they could ill afford to acknowledge Christian advantage on the cultural and spiritual plane. Thus, the vigorous creativity of medieval Europe stimulated its Jews for competitive purposes to create at as high a level as possible, at a level that would enable the small Jewish minority to maintain requisite self-respect.

Language conditions constitute a core aspect of human experience for both individuals and groups. Exchanging the Muslim milieu for Christendom meant a difficult and complex change of language milieu. The change of environment necessitated new language skills for even material success. This change of language had at the same time wide-ranging implications for cultural creativity and achievement.

On the simplest level, Jews had to master new languages for everyday living, and they did so, seemingly rather rapidly. Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes, the great eleventh-century exegete known to the Jewish world as Rashi, attempts to clarify for his Jewish readers difficult biblical and talmudic terms by translating them into the colloquial French of his environment, suggesting that at an early point in their history the Jews of northern France had quickly assimilated to their new language environment. The Jews of northern France were no exception. All across Europe, Jews accommodated to their new language circumstances, adopting the spoken language of their environment as their own. There is only one exception to this general pattern, and it is a major one.

As the Jews moved from German lands into the late-developing areas of eastern Europe toward the end of our period, they maintained their Germanic language heritage, transforming it into the Jewish language of Yiddish. This unusual persistence in maintaining a prior language seems to reflect the sense of profound cultural superiority these Germanic Jews brought with them into eastern Europe. The language milieus of western Christendom differed markedly from that of the Islamic-Arabic sphere. In the Muslim world, Arabic was both the spoken and written language. This meant that the Jews of the Muslim world mastered simultaneously oral and written communication—they were readily conversant with the cultural products of their creative environment. A giant figure like Moses ben Maimon (Maimonides)—distinguished scientist, philosopher, and rabbinic authority—was supported in his scientific and philosophic creativity by intimate familiarity with the creative figures of his environment and their ongoing productivity.

The language situation in the Christian world was radically different; western Christendom was a dual language world, with Latin serving as the written language—at least for many centuries—and a variety of Romance and Germanic dialects serving as the spoken vernaculars. This dual language situation had two major implications for the European Jews. In the first place, it meant that Jews did not develop the easy access they had previously enjoyed to the cultural riches of majority society. The social distance between the Christian majority and the Jewish minority—already considerable—was augmented by a written language barrier. At the same time, the result of this distance was the elevation of Hebrew to the written language of the Jews of Europe. Whereas most of the creativity of the Jews in the Muslim world was couched in Arabic, the Jews of Europe created almost exclusively in Hebrew, enriching that historic language in multiple ways.

Given the splendid creativity of the Jews in the Muslim world—especially during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Jews of western Christendom had to commit themselves to a major translation effort, in order to insure that the riches created in the Islamic-Arabic milieu would remain alive and accessible in the new non-Arabic environment. This translation effort from Arabic to Hebrew took place in the southern tier of Europe, led by families with roots in the Muslim world. The most famous and prolific of these families was the ibn Tibbon family, which over a number of generations excelled in the translation enterprise. The translation effort was a distinct success, enabling Europe’s Jews to enjoy the fruits of Jewish creativity in the Islamic world.

The Jewish translation effort took place against a broader background of cultural transitions. The medieval Muslims had made the riches of Greco-Roman culture available through translation into Arabic. As western Christendom matured, its intellectual leadership recognized the need for yet a second stage of translation, from Arabic to Latin. In this way, masterpieces like the scientific oeuvre of antiquity and the philosophic works of Aristotle became available to the creative thinkers of western Christendom. Given their broad language abilities, many Jews of southern Europe went beyond the Jewish translation effort and lent their talents to the broader Arabic to Latin transition in the larger society around them.

For medieval Jews, the cornerstone of Jewish communal existence was adherence to the dictates of Jewish law, thus transforming knowledge of the law into the basis for religious authority, as we have seen, and into a central intellectual concern of the community. Knowledge of Jewish law developed in three major ways—through a lively responsa literature, that is through engagement with the ever-changing realities of everyday life; through engagement with the classical text of Jewish law, that is the Babylonian Talmud; and through the compilation of new codes, which would make expanding Jewish law—developed through the proliferation of responsa and talmudic commentaries—readily accessible in manual format.

In the medieval Muslim world, central institutions for the study of Jewish law had developed already in late antiquity. Among the functions of these academies was serving as a resource of last appeal for questions that local religious authorities could not answer. Early in our period, the Jews of Europe had occasional recourse to these great academies. With the passage of time, however, this connection was severed, and the Jews of Europe achieved independence from the academies of Mesopotamia. They did not, however, produce the same kind of central academies. Rather, authority to answer the most difficult religious questions of the age devolved upon individual teachers, renowned for their mastery of the Talmud and for their impressive reasoning abilities. The responsa written by these distinguished authorities enabled adaptation to ever-evolving circumstances, were carefully preserved, and formed an important element in the expanding corpus of Jewish law.

Study of the Talmud text formed the core curriculum of the advanced Jewish schools of medieval western Christendom. The comments of especially gifted teachers were written down and disseminated. These commentaries were produced all across Europe, but the most revered and influential were composed in the relatively young Jewish communities of northern France. Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes (Rashi) was the author of a massive commentary on the Babylonian Talmud. This commentary addressed the needs of students at all levels, offering diverse forms of clarification of the difficult talmudic text. Rashi’s comments begin with clarification of the precise wording of the text. Repeatedly, he begins his comments with the indication- “This is the proper reading.” At the next level, Rashi clarifies difficult terms, explaining them through recourse to the spoken French dialect of his day. He proceeds beyond this rather elementary assistance to lead the student through the intricacies of the talmudic argument, usually via an elaborate paraphrase of the text. Rashi’s commentary achieved influence throughout Europe and subsequently throughout the medieval Jewishworld. Eventually—from the Middle Ages to the present, to study the Babylonian Talmud meant in effect to study it with the commentary of Rashi.

Northern-French Jewish study of the Talmud proceeded beyond Rashi, during the twelfth century, to a more advanced level. The initial leaders of this new movement in Talmud study, called the Tosafists, were in fact biological descendants of Rashi, his grandsons. Building upon the prior contribution of Rashi, the Tosafists undertook the daunting task of establishing concord between seemingly contradictory passages in the vastness of the Talmud. Interestingly, the effort at resolution of ostensibly divergent views was the central preoccupation of the students of Church law and Church theology at precisely the same time. Whether there was a causal relationship among these concurrent efforts remains an unresolved issue. In any case, the commentaries of the Tosafists too, while aimed at more advanced students of the text, won widespread admiration throughout western Christendom and introduced a new style of talmudic study that remained in vogue all through the Middle Ages and down to the present.

Given the richness of the response literature and the vistas opened by the new-style Talmud study, the details of Jewish law expanded exponentially during our period, necessitating recurrent efforts at compilation of new compendia of Jewish law. The most influential European compendium was composed on the Iberian peninsula by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher, a pan-European master of Jewish law. Jacob’s father, Rabbi Asher ben Yehiel, was a distinguished master of northern-European talmudic traditions and methodologies. In the early fourteenth century, the accelerating difficulties of Jewish life in the German lands moved Asher ben Yehiel and his family to make their way southward onto the Iberian peninsula, where the paterfamilias quickly assumed a leadership role. Thus, Jacob ben Asher was equipped with wide-ranging knowledge of the customs and commentaries of both north and south, making his compendium of Jewish law—the Arba`ah Turim (Four Towers)—especially comprehensive. It won admiration and authority across most of the Jewish world.

The centrality of Talmud knowledge and study is widely reflected in medieval Jewish life—in the school curriculum, in the oeuvre of innumerable creative thinkers, and in Christian awareness as well. We recall how the thirteenth-century Church slowly became cognizant of the Talmud and its centrality to Jewish life, how it then attempted to vilify the Talmud and have it prohibited, and almost concurrently how it attempted to exploit the Talmud in its missionizing argumentation. It is also worth remembering the case made by the rabbis of northern Europe that, without the Talmud, Jewish life was unsustainable, meaning that the Talmud could not be prohibited without undermining the basis toleration of Judaism that was the cornerstone of Church doctrine and policy. That Pope Innocent IV accepted this Jewish argument is yet further testimony to majority awareness of the centrality of the Talmud and Jewish law to medieval Jewish life.

The importance of the Talmud to medieval Jewish life should not, however, obscure the centrality of the Hebrew Bible on the medieval Jewish scene. The Bible, in different ways, formed the second pillar of Jewish life in medieval western Christendom. It was firmly planted at the heart of Jewish liturgy, bringing every Jew into constant contact with it; it was the grounding for the sermons that served as the central form of life-long Jewish education; it supplied the major symbols that oriented Jewish living in normal times and during periods of persecution and stress; it absorbed the creative energies of leading figures in the Jewish communities of both south and north; it served as the foundation upon which innovative thinkers in the realms of Jewish mysticism and philosophy built their systems; it was the major bone of contention in the historical and ongoing Christian-Jewish debate.

Study of the Bible was part and parcel of the school curriculum, especially in its earliest phases. In a sense, Bible study continued all through a Jew’s life, via engagement with Jewish liturgy in both the synagogue the home. The daily and holiday liturgy was (and is) replete with numerous biblical passages and images, and the major Jewish festivals of the year were (and are) rich in recollection of biblical happenings and symbols. Thus, every Jew attending synagogue or celebrating a Passover seder at home was in fact fully engaged with the Bible at one or another level. This basic engagement was deepened by the sermons regularly delivered by the rabbis, which were based on biblical verses and incidents. Through these sermons, biblical perspectives, themes, and symbols were regularly reinforced. Not infrequently, the rabbis engaged Christian use of shared biblical perspectives and imagery, arguing vigorously to their congregants that Christians in fundamental ways misread and misused the sacred text.

We recall the unanticipated and unprecedented assaults of 1096, which cost many Jewish lives in the Rhineland area and which unleashed a passionate and radical martyrological response on the part of the beleaguered Jews. The reports of these Jewish counter-crusade reactions suggest that—like the attackers, who were deeply influenced by biblical paradigms and symbols—the Jews of 1096 were similarly moved by their own reading of biblical paradigms and symbols. The Jews of 1096 seemingly modeled their behaviors on that of biblical figures like Abraham and Daniel and were stimulated by radical interpretation of biblical symbols like Jerusalem and its sacrificial cult. It did not, however, take extreme circumstances for medieval Jews to see their world through the prism of biblical paradigms and symbols—this is precisely the way medieval Jews read their everyday existence.

Bible commentary absorbed the energies of many of the most important intellectual figures in the Jewish communities of the entirety of Europe. Once again, Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes emerged as a dominant figure, both in terms of his own writings and his stimulation of followers. Rashi’s commentary on the Bible has been—if anything—even more popular than his Talmud commentary. It was read widely throughout the Middle Ages and continues to be studied in traditional Jewish schools down to the present. Once again, Rashi begins on the simplest level, explaining the meaning of obscure words and phrases. He then proceeds to seek the direct and straightforward meaning of the text. In addition, Rashi regularly connects the Bible—the Written Torah—to the various strata of the Oral Torah tradition, suggesting that the two are intimately linked as dual forms of divine revelation. There is some scholarly disagreement as to the extent that Rashi engages in his commentaries Christian readings of the Bible.

Once again, Rashi’s work—especially his pursuit of the straightforward meaning of the biblical text—set in motion a following. Across northern France during the twelfth century, a group of Jewish scholars, once more led by one of his grandsons, developed this direction of Rashi’s exegesis brilliantly, writing a series of commentaries in search of the plain and direct meaning of the biblical text. Here again, the Jewish interest—this time in straightforward exegesis—ran parallel to Christian proclivities of the time. A series of Christian exegetes in twelfth-century northern France likewise devoted themselves to the direct meaning of the Bible. In fact, a number of these Christian exegetes mention specifically consulting Jewish scholars for their expertise in Hebrew or quote and engage overtly the writings of Rashi.

The Jews of southern Europe drew on the legacy of their Iberian predecessors, especially their advances in the scientific study of the Hebrew language. Lexicography, grammar, and syntax had all been explored by Jews living in the Muslim world, and that heritage was maintained by the Jews who were absorbed or migrated into the Christian sphere. Perhaps the most widely read and admired of the twelfth-century southern exegetes was David Kimhi (Radak), whose father had brought the family out of Spain and over to Narbonne in southern France. Kimhi’s commentary is rich in penetrating philological observations. In addition, Kimhi—profoundly committed to rationalism—sought to explain biblical materials contextually, always with a commitment to portrayal of biblical thought and imagery as thoroughly compatible with reason. With David Kimhi, there can be no question as to his concern with Christian readings of Scripture. He regularly cites what he sees as Christian misreadings and rebuts them at considerable length.

The towering thirteenth-century Jewish Bible exegete was Rabbi Moses ben Nahman (Ramban)—a major communal figure in Iberian Jewry, the Jewish interlocutor in the important proselytizing disputation held in Barcelona in 1263, a brilliant expositor of Jewish law, a leader in the newly emerging tendencies toward mysticism, and a biblical exegete with profound literary sensitivities. The Ramban’s commentaries are rich in literary awareness and insight. He plumbs deep levels of the biblical narrative and biblical characters. Occasionally, he hints at the yet deeper mystical meanings of the biblical text, although he is fully committed to maintaining mystical insight as the preserve of a limited and cautious minority of his community, not to be shared with the broad Jewish populace.

The search for the deeper meaning of received texts and traditions is a constant of religious communities, and the Christian majority and Jewish minority of medieval western Christendom were no exceptions. Within the Christian majority, numerous mystical and pietistic groups emerged. To an extent, the Roman Catholic Church was successful in absorbing many of these groups into its fold; some of these groups, however, seemed to cross the boundary into heterodoxy, giving rise to the perceived proliferation of heresy and the elaboration of repressive mechanisms for dealing with what was viewed as a dangerous threat. The same creative forces are evident in the Jewish world as well, where new interpretations of the biblical and rabbinic texts and traditions abounded as well.

In northern Europe, the most potent of these new tendencies was to be found in the Rhineland area, in a twelfth-century movement dubbed by modern scholarship Hasidei Ashkenaz (The German Pietists). This loose movement was headed by some of the most venerable and illustrious rabbinic families in the area. These thinkers advanced novel understandings of traditional biblical imagery, and their heretofore-unpublished writings are slowly being edited and analyzed. The pietistic teachings of this group have been far better known. The major repository of these teachings is the well-known Sefer Hasidim, a compilation of many literary forms, perhaps most prominently didactic tales with moral and ethical directives. These teachings generally take a radically negative view of surrounding Christian society, urging upon the pious believer extremes of self-abnegation.

Mystical speculation was somewhat broader and more diversified across the southern areas of Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. These diverse mystical movements advanced alternative methods for plumbing the deep secrets of the universe, involving a variety of reinterpretations of traditional Jewish teachings and behaviors. With the passage of time, one mystical stream became increasingly prominent, that called loosely theosophic Kabbalah. This version of medieval Jewish mysticism posited a multi-faceted divinity, whose various sefirot or sectors interacted dynamically with one another and with the lower levels of the universe as well. As this tendency matured and achieved preeminence, its adherents produced the classic work of medieval Jewish mysticism, the Zohar.

The Zohar is a sprawling and dense work, composed of many independent sections, most in Aramaic and some in Hebrew. The Aramaic of the Zohar is part of an effort to project the work as a composition of late antiquity, with the second-century Rabbi Simon Bar Yohai as the purported author. Much of the material in the Zohar takes the form of mystical commentary on biblical passages, often supplemented by lengthy homilies. A circle of adepts stands at the center of much of the material. Modern scholarship has posited a late-thirteenth-century Castilian Jewish mystic, Moses de-Leon, as author of the Zohar, suggesting that the views in the book represent the mystical system developed by Jews of thirteenth-century Castile. The work won wide authority and emerged as the classical work of medieval Jewish esotericism.

The diverse mystical Jewish tendencies that sprang up all across medieval western Christendom inevitably aroused a variety of responses, some positive and some negative. They did not, however, elicit strong perceptions of heterodoxy; by and large they were comfortably accommodated within the Jewish community. The fact that many of these mystical tendencies were supported by distinguished rabbinic authorities contributed to the broad sense that the innovative mystical thinking did not cross over into heresy and did not have to be formally challenged and repudiated. Jewish philosophic thinking was quite different in this regard. While many distinguished rabbinic authorities lent their prestige to the philosophic enterprise, significant numbers of Jews were convinced that philosophy was an unwelcome intruder in Jewish life and that it would lead eventually to negation of fundamental Jewish principles and values.

Jewish philosophic speculation represented yet another effort to reach a deeper understanding of Jewish texts and traditions. Unlike mystical speculation, philosophic speculation began with a distinct external challenge. As the fruits of Greek and Roman scientific and philosophic thought began to surface, first in the Muslim world and eventually in western Christendom, some Muslim, Christian, and Jewish thinkers became convinced that there was truth in the Greco-Roman thinking and that the traditional thinking of their own communities was fully consonant with that truth. Proving the compatibility of philosophic truth with traditional Muslim, Christian, and Jewish teachings became an obsession for some; for others, these efforts threatened the very fabric of traditional religious life. The battle was intense and protracted, often leading into political controversy. The books of Thomas Aquinas were burned in Christian majority society; the views of Maimonides and his followers were banned in the Jewish minority community.

The initial step in setting philosophic speculation on its course in medieval western Christendom was part and parcel of the translation efforts noted earlier. Many philosophic texts in Arabic were translated, but none was more significant than the ibn Tibbon translation of Maimonides’s philosophic magnum opus, his Guide for the Perplexed. Maimonides was one of the great masters of the rabbinic corpus; his code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah, was a masterpiece and was widely acclaimed. Yet some of his rabbinic teachings, framed in ways that would make them fully compatible with the dictates of philosophic reason, aroused opposition; his philosophic masterpiece was yet more inflammatory.

By the 1230’s, barely a quarter century after the death of Maimonides, the Jewish communities of southern France were embroiled in a wide-ranging dispute over Maimonidean teachings. One camp saw in these teachings an undermining of Jewish law and the beginning of the unraveling of the entirety of Jewish tradition and religious life. The other camp saw Maimonidean teachings as utterly correct and—even more important—critical to the maintenance of Jewish tradition. Without Maimonides and his teachings, the latter camp argued,the Jewish world would be held up to the ridicule of the intelligentsia both non-Jewish and Jewish. Jewish survival necessitated recognition of the importance and accuracy of the Maimonidean formulations.

This dispute—intense and bitter—ranged all through the European Middle Ages. When crises developed, for example the massive conversions that accompanied the physical violence of 1391 on the Iberian peninsula, each side blamed the other for what had gone wrong. For the anti-Maimunists, philosophic thinking had undermined traditional Jewish faith and had sapped the energies of a once vibrant community. For the Maimunists, too little—rather than too much—philosophy lay at the heart of what was perceived as a debacle. Interestingly, the dispute has in a sense not died down yet, as modern students of the Jewish past continue to disagree over these matters.

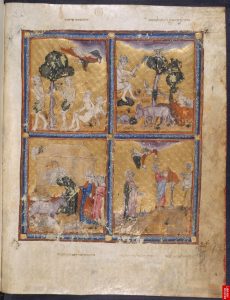

The Jews of medieval western Christendom created in many other ways as well—they fashioned rich works of art, wrote fascinating poetry and prose, and composed striking historical narratives detailing both the ancient Jewish past and contemporary or near-contemporary events. While much of this further creativity cannot be discussed here, one more area of Jewish intellectual and spiritual endeavor demands acknowledgement, and that is Jewish polemical literature. As noted recurrently, medieval western Christendom was aggressively committed to missionizing among its Jews. This aggressive posture began to manifest itself by the twelfth century, and by the thirteenth century it had generated a well-organized campaign to force Jews into confrontation with a range of new arguments. In the face of this aggressiveness, Jewish leaders had to provide guidance to their followers, and they did so. Once again, the style of argumentation varied widely in the different sets of Jewish communities.

Common to Jewish argumentation in all sectors of Europe was a focus on the Hebrew Bible, with identification of major Christian arguments grounded in biblical verses and repudiation of these Christian arguments. There were a number of broad Jewish methodological positions that undermined in general ways Christian readings of Scripture. They included insistence that Christian views were misled by erroneous translation of the Hebrew text and that Christian exegesis was regularly decontextualized, obscuring the simple and straightforward meaning of the biblical text. Beyond these broad stances, Jewish polemicists challenged the particulars of Christian readings on hundreds of verses. These challenges are sometimes found in the general commentaries of such luminaries as David Kimhi; sometimes entire works of polemically-oriented biblical commentary were composed.

While Christian missionizing argumentation and Jewish rebuttal was grounded in divergent understandings of the Hebrew Bible, both extended into other arenas as well. With the growing place of philosophic thinking within both communities, Christians advanced arguments for the philosophic truth of Christianity, while Jews vigorously denounced such key Christian doctrines as Incarnation and Trinity as obviously irrational. Another basis of disagreement involved the moral stances of the two communities. Christians pointed to heavy Jewish involvement in money-lending as evidence of lower moral standards; Jews attacked many facets of Christian behavior, focusing heavily on the bellicosity of medieval Christian society and what Jews perceived as sexual licentiousness.

Both the philosophic argumentation and cases made from comparative moral achievement constituted lines of polemical argumentation with which the Jews of medieval western Christendom felt relatively comfortable. The most uncomfortable Christian attacks were those that focused on the disparity in material circumstances of the two faith communities. Jewish polemical works regularly portray Christian thrusts drawn from the successes of the Christian world and the debased circumstances of the Jews. This disparity is taken to reflect divine favor of the Christian camp and divine abandonment of the Jews. Hearing Christians advance this line of polemical argumentation was difficult for medieval Jews, but their leaders pondered the issue deeply and provided lines of response. Interestingly, Jews did not deny the realityof superior Christian material circumstances. They did, however, argue that Christian successes did not meet the criteria of messianic redemption, suggesting that Jesus was in fact not the promised Messiah. With the passage of time, as the early successes of the crusades dimmed, and Muslim resistance stiffened, Jews sometimes argued in more relative terms that—if material circumstances were taken as reflecting divine favor—then God obviously prefers Muslims to Christians.

These attacks on Christian achievement were useful, but they still left the issues of Jewish dispersion, small Jewish numbers, and Jewish political subjugation unanswered. Jewish polemicists all across Europe denied that Jewish suffering was a sign of abandonment by God; they claimed, rather, that the tribulations suffered by the Jews were a divinely imposed test. Steadfastness in the face of a divinely imposed test had won rich promises by God to the patriarch Abraham; subsequent Jewish steadfastness would win similar rewards for his descendants. In the face of the early assaults of 1096, the Jewish chroniclers of these bloody attacks portray sympathetic Christian onlookers urging their Jewish neighbors to acknowledge divine abandonment and convert. In reply, the chroniclers make the case that the assaults were a test, that the Jews of 1096 had responded in exemplary fashion, and that the result of this Jewish heroism would be immediate individual reward for the martyrs in the next world and eventual reward for their descendants in this world.

The Jews of medieval western Christendom faced serious material obstacles and overcame them to create an enduring Jewish presence in this emergent center of the Western world. They likewise encountered major spiritual challenges and overcame them as well. The Christian majority was deeply committed to winning over these Jews and made major efforts—informal and formal—in that direction. Conversion of Jews was a reality all through our period, although the numbers were generally not significant, with the exception of the crisis period on the Iberian peninsula during the closing decade of the fourteenth century and opening decades of the fifteenth century. The Jewish successes in creating effective Jewish communal structures and in fashioning a competitive Jewish culture in general and Jewish polemical counter-arguments in particular were as important to the successful implanting of Jews in medieval western Christendom as the material successes.

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website