Ottoman Conquest, 1517-1699

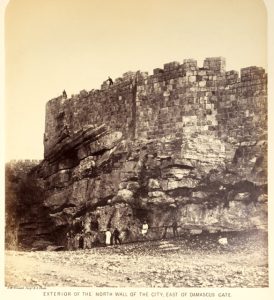

Exterior of the North Wall of the Old City

The Ottoman star was very much in the ascendant by the time Selim I reached the throne. (“Ottoman” is a corruption of “Osmanli,” the name of the Turkish dynasty founded by the sultan Osman I at the end of the thirteenth century.) Constantinople had fallen to the Ottomans in 1453, and they had overrun what was left of the former great Byzantine Empire. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, they already controlled Asia Minor and parts of Europe and the Balkans. Selim I, who reigned from 1512 to 1520, added Syria and Egypt to the Ottoman Empire in 1516 and 1517.

Jerusalem—and the rest of the country—fell to him almost without a battle. Selim occupied himself little with the Holy City; he lived only three years after its conquest, and in that time was busy elsewhere on campaigns. The sultan who did, and who left an impressive mark on Jerusalem, was his son, Suleiman I—the Magnificent as he became known in the west, and as the Lawgiver in Turkey. He reigned from 1520 to 1566.

The walls surrounding the “Old City” of Jerusalem which we see today are the very walls, unchanged, which Suleiman rebuilt. Like Hadrian’s Aelia Capitolina, the southern wall runs just north of, and thus excludes, Mount Zion. Suleiman’s walls have a clean-lined beauty, reflecting artistic taste and fine craftsmanship. They are given a special quality—which must also have been true of the ancient walls—by the natural rose-color or the local stone. At sunset, the ramparts glow.

Pride of Suleiman’s wall structures was the Damascus Gate, which he built anew. (Archaeological excavations brought to light parts of the second century gate on this site, no doubt the one which appears so prominently on the sixth century Madeba map.) This gate, in the center of the north wall of the city, was—and still is—one of the riches examples of early Ottoman architecture in the region, massive-looking yet graceful. The arched portal is set in a broad façade flanked on each side by a great tower, the entire building topped by pinnacled battlements. The staggered entrance is handsomely vaulted. It all looks powerful enough. Yet the Damascus Gate is more decorative than defensive and seems to have been designed as much to impress the distinguished visitor as the enemy. One curious feature is the rows of bosses above the portal, the lower one adorned with reliefs of flowers and geometric patterns. They appear to be the protruding ends of binding columns running through the wall to strengthen the structure. But they are fake. There are no such columns.

For long, the Damascus Gate was where foreign dignitaries were received, such as the crown prince of Prussia and the emperor Franz Joseph of Austria in 1869. Later the Jaffa Gate was used; it was through here that the German Kaiser in 1898 and General Allenby in December 1917 entered the city.

Work on the walls took three years and was completed in about 1540. Earlier, Suleiman had added decorative adornments to the Dome of the Rock, which have been described earlier, and to the Hara mesh-Sharif generally. He also improved the water services of the city, repairing the aqueducts, building a number of public fountains (sabils), and restoring the dam which forms the ancient Sultan’s Pool at the western foot of Mount Zion.

Under Suleiman’s efficient rule, Jerusalem prospered modestly. Christians and Jews were subject to the special poll tax which all non-Moslems had to pay, but both were left free to manage their own communal affairs. The Franciscans suffered a blow when in 1551 they were expelled from their church and monastery on Mount Zion adjoining the Coenaculum, traditional site of the Last Supper, but they were provided with alternative ground in the Christian Quarter inside the city walls, where they built the monastery of St. Saviour’s. It still stands as their headquarters.

Under Suleiman, the Jewish community of Jerusalem fared reasonably well. Indeed, within the wide area of Ottoman rule, they suffered little of the persecution that was their lot notably in Spain, Portugal, Germany and central Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In 1492 had come the great expulsion from Spain and four years later from Portugal. With the French frontier closed, they fled by sea to the nearest refuge, Italy and North Africa, or further, to the Levant. Then came persecution in Italy. But in Palestine under the Ottomans they could practice their religion freely. Many reached the Holy Land in this period, and while most flocked to Safad and Tiberias, centers of Jewish study in Galilee, the community in Jerusalem grew both in numbers and learning.

Decline set in only a few decades after Suleiman’s death, and from then until the end of the Ottoman Empire more than three centuries later, Palestine was a land in decay, neglected, impoverished, lawless, corrupt.

Jerusalem could not but be affected by the desolation of its hinterland. It was affected more directly by the get-rich-quick aim of its own local ruler. Urban society offered him countless opportunities. A permit to build was a double source of revenue- the bribe extorted to secure the permit, and the official cost of the permit. So was a permit to carry out repairs, or to acquire land. Moreover, a newly installed pasha could repeat the process of double extortion which the victim might already have gone through with his predecessor. The possibilities were endless.

The Christians in Jerusalem were well aware of them, yet their bitter internal rivalries greatly stimulated the practice of extortion. There was the centuries’ old hatred between the western and eastern Churches and conflict among the eastern sects themselves. Since each sought to increase its rights in the Holy Places, the Turks were happy to sit back and await the highest bids.

One of the most remarkable phenomena of Ottoman Jerusalem was the survival—and eventual growth—of the Jewish community. We have seen how the Jews, in common with all the inhabitants of the city, fared quite well under Suleiman I at the beginning of Ottoman rule. We have also seen what started happening to the land and the people later in the sixteenth century, and how it kept growing worse. Once the administration started to decay, all suffered. The Jews fared worst of all. The Christians had their protectors—the Latins in the west, the Greeks in Constantinople and Moscow. The Jews had none. Their fate was determined by the whim of the pasha—or of his underlings, or of the Moslem in the street. Persecution was their normal lot—disabilities, restrictions, extortion, humiliation; murder or physical injury were frequent hazards. But still they came, as pilgrims and as settlers, to their beloved Jerusalem.

Gone were the days when Ottoman tolerance could attract to its provinces Jews fleeing from Christian persecution in Europe. In the 1580s, the local pasha could seize the chief synagogue in Jerusalem of the Sephardim (Spanish Jews), the thirteenth-century synagogue of Nachmanides (the Ramban), and declare that it would be used as a mosque—thereby making it inalienable Moslem religious property and denying it permanently to Jews. (During the recent Mandatory and Jordanian periods it was used as a food-processing factory.) Still, the Jews could, and did, with painful effort and bribery, establish another synagogue shortly afterwards—on the traditional site of the synagogue of the first century’s celebrated Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai. This in our own day was the oldest synagogue in Jerusalem, and in continuous use from the sixteenth century until 1948 when it was destroyed by the Jordanians.

Jerusalem had a brief spell of fair administration from 1620 to 1625 under the governorship of Mohammed Pasha, and this is reflected in the following record written a few years later by a Jerusalem Jew who had lived through the period-

“The City of God contained more of our people than at any time since the Jews were banished from their country. Many Jews came daily to live in the City, apart from those coming to pray at the Western Wall… Moreover, they brought with them bountiful gifts of money to strengthen the Jews of Jerusalem. It was reported in all countries that we were dwelling in peace and security. Many of us bought houses and fields and rebuilt the ruins, and aged men and women sat in the streets of Jerusalem, and the thoroughfares of the City were thronged with boys and girls… The teaching of the Holy Law (the Torah) prospered, and many houses of study stood open to all who sought to engage in the labour of Heaven. The leaders of the community provided the students with their daily needs. All the poor were relieved of their wants…”

The idyll was short-lived. The next pasha of Jerusalem, Mohammed ibn-Farouk, who had bought the governorship from the senior pasha in control of the vilayet of Damascus, arrived in the city with three hundred mercenaries intent on multiplying his investment. One method was to surround the synagogues on the Sabbath, seize the leading figures among the worshippers, and hold them for high ransom. When this was paid, and the community was just about recovering from the financial blow, the pasha would order a synagogue to be impounded and converted to stores—unless a large payment was forthcoming to prevent the sacrilege. On one occasion, when two congregants were grabbed and the impoverished community was finding it difficult to raise the money for their release, the victims were brought to the synagogue and torture before the eyes of the congregation. Household chattels were sold or pledged to speed the payment.

The city “contained more of our people,” the Jerusalem Jew had written, than at any time since the exile. He was writing in the early part of the seventeenth century when the total population of Jerusalem was about ten thousand and the Jews numbered only a few hundred. Two hundred years later, the general population still stood at the same figure, but the Jewish community had grown to three thousand. Despite the misery and the suffering, there were always groups in the Diaspora who were prepared to brave life, however hard, in the Holy Land. By the third quarter of the nineteenth century, the Jewish population of Jerusalem had grown to some eleven thousand and they constituted the majority—for the first time since their independence—a majority they were to retain to this day, when they number nearly two hundred thousand.

Excerpted from Ottoman Jerusalem 1517-1917, Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem: Sacred City of Mankind, Steimatzky Ltd., Jerusalem, 1991.

Artifacts

- Mohammed Manuscript, 16th century

- Jews from Worms, 16th century

- Silver Lion Dollars, 16th-17th century

- Martin Luther Burns the Papal Bull, Dec. 10, 1520

- Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520-1566

- Suleiman the Magnificent Inscription, 1520-1566

- Firman on the Western Wall

- Tyndale New Testament, 1526

- Nicolaus Copernicus’ Theory of Heliocentricity, 1533

- Rebuilding of the Walls of Jerusalem, 1538-1541

- Damascus Gate, 1538

- The Zion Gate, 1540

- Pilgrims Arrested, 1556

- Galileo Galilei, 1564-1642

- Battle of Lepanto, 1571

- Drawing of Jerusalem, 1581

- Itinerary of the Holy Land, 1598

- King James Bible, 1611

- Nicolas Poussin’s Destruction of Jerusalem, 1625-26

- Walton Polyglot Bible, 1654-1657

- A Journal of the Plague Year, 1665

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website