• Arab nationalism is a relatively new concept, born of Western imperialism in the early part of the 20th century. What defines an Arab? The Arabic language? Citizenship in an Arab country?

• Arab nationalism is a relatively new concept, born of Western imperialism in the early part of the 20th century. What defines an Arab? The Arabic language? Citizenship in an Arab country?

The Muslim faith? The term “Arab” is believed to have first been used in the 9th century, B.C. in reference to the nomadic Bedouin of northern Africa. The Greeks and Romans used it when talking about the Arab peninsula, and during the Arab empire and her conquests outsiders referred to everyone within the Empire, utilizing the Arabic language and traditions (regardless of religion or race) as Arab.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 16-17.

• In understanding the process of researching and writing about the Arab people, the author points to the fact that western authors write from a western perspective, using western terms. This can be very limiting when trying to successfully understand and convey information about a culture whose societies are formed based on different influences and with a different system of values. An excellent example is the concept of Church and State, which until recently did not have separate translations in Arabic. Islam views the Church and the State as one, “indistinguishably interwoven”.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 19-20.

• The Winkler-Caetani theory was developed to explain the origins of the Arabs. It states that Arabia was the home of all Semitic people, and a land of great agricultural fertility. Over time, the waterways dried up and turned into the deserts we know of today, causing productivity in the region to fall, and hardships for the people living there. This, combined with multiple invasions from other people caused a great dispersion of Arabia’s original inhabitants, forced the early Syrians, Aramaens, Phoenicians and Hebrews as well as the “Arabs” out into the Fertile Crescent.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 22-23.

• Southern Arabia is believed to have been a highly developed agricultural society, with divided properties, dams and canals, producing spices, cereals/grains, incense and myrrh. They practiced a polytheistic religion, similar to other ancient people, and their spice crops were considered sacred, with a large portion being given to their gods and priests. Writing was used in the form of inscriptions, although apparently not for books or literature.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 25.

• In northern Africa, before the rise of Islam, the social structure was mainly Bedouin tribalism. Lewis describes this in the following manner-

“In Bedouin society the social unit is the group, not the individual. The latter has rights and duties only as a member of his group. The group is held together externally by the need for self-defense against the hardships and dangers of desert life, internally by the blood-tie of descent in the male line which is the basic social bond… It is by a chain of mutual raiding that commodities from the settled lands penetrate vi\a the tribes nearest to the borders to those of the interior.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 29.

• The nomadic religion was similar to the paganism of the ancient Semites, with gods and beings found in places such as trees and rocks, as well as more powerful gods, including the three most important, Manat, ‘Uzza and Allat., overseen by the most powerful, Allah. The Bedouin carried these gods with them in a red tent as they traveled, even taking it into battle.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 30.

• Occasionally, more sedentary communities could be found living near an oasis. If one oasis community succeeded in taking over a near-by oasis, a small “empire” was formed, with one leading family (much like a kingship or monarchy). Kinda is historically the most important of these oasis societies, for the influence it had on Islamic expansionism. Peaking during the late part of the 5th century and early 6th century, Kinda is attributed with the development of Arabic poetry, both in language and technique, thus providing Arab tribes with a form of cohesive oral culture.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 30-31.

• Many foreign communities settled in the Arab peninsula as well. Jews and Christians established themselves in different parts of Arabia, bringing Aramaic and Hellenistic cultures with them. Najran was the Christian center in southern Arabia and Yathrib, which would later be called Medina, was a capital for Jews and Judaised Arabs.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 31-32.

• Outside people and cultures penetrating into Arabia brought a great deal of change to the Arabs. They now had access to arms and saw the benefits of organized military and strategies. They were introduced to wine and food and textiles that they had not known before. Writing was introduced as a mechanism of culture. And religiously, they were exposed to the ideas of monotheism and the moral ideas brought by the foreigners. The early foundations for the prophet Muhammad and Islam can be traced here.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 33.

• Hadith refers to “traditions” supposedly passed down from the Prophet in an oral tradition. As a means of controlling the huge numbers of Arabs now encompassed by the empire (far greater in size than Muhammad had ever known), rules and laws for governing were drawn not only from the Qur’an itself but also from the Sira, a biography of the daily, traditional life led by the Prophet. These “hadiths” did not really begin to appear until almost 7 generations after Muhammad’s death, so one might be established simply by someone saying,, “Well I heard that…………., from so-and-so, who heard it from….., who heard that the Prophet had directly said…..” and thus a new edict or guide could be set. It is clear how this practice might have easily, and often been abused in order to facilitate one particular person or group’s needs.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 36.

• Although the Muslims realized the faultiness of this process of turning hadiths into law, their measure for correcting it did little to solve the problem. With the idea that “false” hadiths could be edited out by truly tracing their lineage, it simply opened up the possibility for new rivalries and feuds to begin. (For example, a “researcher” might determine a particular relater to be untrustworthy based on his family, an old feud, etc…) And as the author, Bernard Lewis, points out, “It is as easy to forge a chain of authorities [as it is] a tradition.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 37.

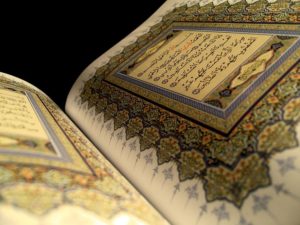

• Muhammad received his Call when he was almost 40 years old. Circumstances were ripe, as many people were becoming dissatisfied with the pagan faiths, but were not interested in Christianity or Judaism, either. The Meccans tolerated Muhammad and his teachings, as he seemed to pose no immediate threat. The early part of the Qur’an focuses mainly on the evilness of idolatry and the importance of the unity of God, not so different from Judeo-Christian roots. It is thought that in the beginning Muhammad likely had no intentions of developing and spreading a new religion, but more likely simply wanted to bring “enlightenment” to his community, similar to the stories he had heard from the Bible (although not read himself, for he is believed to have been illiterate), in his people’s own language.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 39.

• During the 1800s, a scholar of Islam suggested that the struggle between the then new-born Muslim community, lead by Muhammad, and the dominant “Meccan oligarchy” was truly a class conflict, with Muhammad and his followers represented the “under-privileged and their resentments against the ruling bourgeois oligarchy.” Although not entirely true, it is known that the Prophet received much of his support from the poorer classes and those resenting the money and wealth held by the Meccans. However, as they were ultimately unsuccessful in converting the dominant class in Mecca, Muhammad and his followers eventually moved onwards, toward Medina.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 39-40.

• Originally settled by Jews from the north, Medina (called Yathrib before Islam) attracted throngs of pagan Arabs with its richness and prosperity, and was ultimately dominated by them. Medina lies approximately 280 miles north of Mecca, and at the time had no stable form of government. The feuding rival Arab tribes of Aus and Khazraj were constantly causing turmoil for the town, and both disliked the Jews, who were viewed as more economically advantaged with their agriculture and crafts. Eventually the unity of Islam would allow these Arab tribes to dispel the Jews from Medina.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 40-41.

• Hijra refers to the Muhammad’s move from Mecca to Medina, and is considered to be the turning point of the Muslim faith. Today it marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar. Muhammad himself had been invited by the people of Medina/Yathrib, as they had heard of his spiritual presence and hoped he might be able to help them settle disputes. Because the Medinese were not captivated by paganism like their brothers in Mecca, they were open to the new ideas that Muhammad and his followers brought with them, and accepted the religious aspects of Islam after taking in the social system which provided a much needed sense of structure, security and discipline. The Hijra took place in 622 A.D.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 41.

• The word Ansar came to be known in the Tradition as a word for helpers, or those who supported Muhammad and the word Munafiqun translates loosely as hypocrites. As the Prophet established himself in Medina, now able to practice Islam and not just preach its ideas; he became a large identity that he had been in Mecca. In Medina he was respected, not simply tolerated. Whereas he had been a mere citizen in Mecca, in Medina he was a magistrate. He governed the existing order, rather than simply challenging it as he had in Mecca. But his rule did not come easily. Not everyone hopped on board with the new religion immediately, and although the Prophet had hoped for an easy audience with the Jews (the Muslim practice of praying towards Mecca was initially facing Jerusalem, a practice Muhammad adopted in hopes of enticing Jewish conversion to Islam. Only later did he change the direction of prayer). But the Jews wanted nothing to do with this perceived false prophet and attempted to reject the faith from their community, but to no avail.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 41-42.

• A brilliant move on the part of Muhammad allowed him greater control over the spread of Islam, and is one of the most interwoven concepts of the culture today. Using the political power with which he arrived in Medina he extrapolated it into a religious authority. He developed laws that delineated the relations between different tribes and religions. Meccan immigrants were different from Medinese tribes, and each was different in relation to the Jews. All lived within the Umma, a new community. Jews were allowed to practice their faith and maintain their possessions, as long as they adhered to other laws and agreements. Many tribal elements were still respected and observed with regard to marriage, property and relationships, but all disputes were to now be settled by Muhammad himself. And most importantly, “faith replaced blood as the social bond.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 42-43.

• Over the years, Islam grew stronger, as it also changed and shifted and expanded. Muhammad, now the Sheikh of the Umma in Medina in addition to a religious prophet, wore many hats. His power was not negotiable, as it had been given to him by God, thus giving him complete religious say. Public opinion had little to do with his authority. Much like its leader, the Umma was at once a political community and a religious entity. This dualism would go on to become a hallmark of Islam. And yet the Umma also still engaged in the raiding of other villages and tribes, redistributing the wealth and booty amongst them upon their return, much as their tribal relatives had. But now the loot was considered an act of divine will. As Islam took a stronger footing in the area, Jews and Christians were accused of having changed, or falsified their own religious texts, in attempts to “hide” their true knowledge of Muhammad’s prophecy.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 43-44.

• The Prophet Muhammad passed away in 632, having brought a monotheistic faith to the Arab world and a book that would go on to become a comprehensive guide for thought and conduct to millions. In addition, he created the first well-organized and highly powerful community in Arabia, the Umma in Medina. According to Lewis, ”Today’s traditional Muslim still views Muhammad as the last and greatest of the Apostles of god, sent as the Seal of the Prophecy to bring the final revelation of God’s word to mankind.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp 47.

• An inherent problem resulting from the death of Muhammad was, however, that he had left no successor, or other means for continuation of rule and leadership. Bernard Lewis writes, “The unique and exclusive character of the authority which he claimed as sole exponent of God’s will would not have allowed him to nominate a colleague or even a successor-designate during his lifetime.” But forced to make a decision, the Arabs chose to elect a tribal chief. Abu Bakr became the Khalifa (later translated as Caliph), meaning “deputy” of the Prophet. The only requirements for his new office were to lead in the tradition of Muhammad.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 50-51.

• Other tribes did not accept the appointment of Abu Bakr as successor to the Prophet. For those living farther away from Umma and Medina, the passing of Muhammad simply meant that they would now return to their previous ways of life. They had not elected him, he did not hold a religious position while the Prophet was alive, and they felt no need to follow him now. Abu Bakr thus made the decision to “reclaim” or “reconvert” these tribes by force, in what would become known as the wars of the Ridda. Bakr and his military went after those in Arabia as well as farther out, moving into Iraq, Syria and Egypt. At their beginning, these Arab conquests were likely not so much an attempt to spread Islam as they were efforts to expand Arabia, due to overpopulation.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 51-58.

• The Arabs were not considered to be the worst of the conquering rulers during the time. Compared to the Byzantine rule, Islamic ruled was welcomed by Christians and Jews alike. An apocalyptic writing from Judaism is quoted (an angel speaking to a rabbi), “Do not fear, Ben Yohay; the Creator, blessed be He, has only brought the Kingdom of Ishmael in order to save you from the wickedness [Byzantium]… the Holy One, blessed be He, will raise up for them a Prophet according to His will and conquer the land for them, and they will come and restore it.” In fact, Jews and Christians were often given tax breaks and other assistance under Islamic rule, in exchange for having been so helpful in overthrowing the previous rule.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 58.

• The Caliph Ali left Medina in 656, marking the end of that city as capital for the Islamic Empire. Kufa, through force, became “his” capital. From here he ruled all of the Empire, with the exception of Syria where Mu’awiya held governance.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 62.

• Mu’awiya would succeed Ali as leader of the Arab Empire, but more changes were on the way in order to accommodate his leadership. A great deal of disunity plagued the area now, and the capital would be moved to Syria. The oligarchy in Mecca had been defeated, but the lack of cohesion amongst the Arabs was of concern to the new leader. Mu’awiya planned to move the empire from a “theoretical Islamic theocracy to an Arab secular state, based on the dominant Arab caste.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 64.

• Mu’awiya’s intent to refocus the Empire on the political and economic elements resulted in later historians refusing to acknowledge him as “Caliph” (Although Mu’awiya did not abandon the Islamic faith, even his successors were not considered Caliphs, and the Caliphate is considered to not have resumed until the house of Abbas in 750.) During his reign Mu’awiya decided on a successor by nominating his son Yazid (direct, or automatic blood lineage was not considered an option) and this was “enforced” with bribes rather than force. Yazid would eventually nominate his son, as well.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 66-67.

• Mawali was the term used to describe Muslims who were not fully or originally descendants of an Arab tribe. Persians, Armenians, Egyptians and other converts but not non-converts, who were called Dhimmis (provided they were members of one of the protected religions tolerated by the Empire). The Mawali fought alongside the Arabs, but were compensated less and it was inconceivable that there would be intermarriages. This type of caste, or socially prejudiced system built great discontent among many of the Mawali.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 70-71.

• Many of the Mawali turned their social discontent to a different religious movement within Islam, called Shi’a. It began with roots in support of Ali and his descendants to the Caliphate, and resulted as “ an expression in religious terms of opposition to the state and the established ‘Order’, acceptance of which meant conformity to the Sunni, or orthodox Islamic doctrine.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 71.

• Not surprisingly, Mawali turning to Shi’aism were often more engaged by the more extreme factions. They adopted the idea of a Mahdi, or “rightly guided one” who quickly transformed from a political leader into a false Messianic figure.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 72

• Other factions began to break off from the majority Islam group during this time, as well. The revolt against the more centralized Arabism (contrasted with the older, more religious form) was seen, on different levels. Pietists in Mecca and Medina were successful in undermining the authority of the Umayyad government, through their use of propaganda. The Kharijite began as a solely religious group, but took and aggressive political opposition as they refused to recognize any centralized authority.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 73-74.

• Around 744 the Umayyad Empire began its decline, due mostly to tribal infighting between the Shi’ite and the Kharijite. The very idea of a centralized government was no longer popular amongst the majority, and was refuted even in Syria where it had always found acceptance. The Abbasids replaced the Umayyads as leading dynasty, in a change Lewis refers to as, “…a revolution in the history of Islam, as important a turning point as the French and Russian revolutions in the history of the West.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 78-80.

• The first major change to take place with the shifting dynasty was the move of the Arab Empire’s center from Syria to Iraq. Its location was far more cosmopolitan and centrally located, for Middle East and Asian trade. The Caliphate took on a new flavor as well, running as an autocracy, with the Caliph receiving his power divinely and without input from the masses. The author states, “No longer was he the Deputy of the Prophet of God, but simply the Deputy of God, from whom he claimed to derive his authority directly.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 82-83.

• Geographically and agriculturally, the move to Iraq brought great wealth for the new Caliphate. Crops included wheat, rice, barley, dates and olives and gold, silver and copper were all mined, as well. The Abbasids also expanded on textile production, begun by the Umayyads, which became a vital industry for them in terms of employment as well as production. Chinese prisoners taken during a battle in 751 brought paper to the world of Islam.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 86-87.

• Concurrently, the huge economic changes brought social changes for the Arabs as well. The warrior caste faded over time (although not the use of violence for conflict resolution). A “tribesman” no longer carried the clout he may have in earlier decades and now an upper class of wealthy and educated Arabs was emerging. But the dynasty remained Arab, and Arabic was still the primary language. As the hereditary caste system shifted, the Arabs found themselves welcoming in more Muslims from other ethnic backgrounds, creating a change in the very definition of the term “Arab”.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 92-93.

• The Abbasid dynasty ruled for several centuries and brought changes of many types to the Middle East. Although many were prosperous during this time, revolts were still common. The Zanj were a group of slaves from the salt flats of Basra, mostly black Africans. As they began their revolt, black soldiers were sent in by the Empire to quash them, but more often they joined forces with the Zanj, strengthening their numbers and arms. Over time, the Zanj took control of southern Iraq and southwest Persia, and eventually even invaded Basra, although they did not occupy it.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 104-106.

• The specific revolts of the Abbasid dynasty did not in and of themselves change Arab history, but speak to a growing sense of discontent within the Empire. The Ismaili movement, off-shoot of the Shi’as, had a very extreme and revolutionary tinge to it. Different from traditional, orthodox Islam, Ismaili incorporated neo-Platonic ideas and Indian thought, and viewed the Qur’an as having two meanings, a literal and an esoteric.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 106-108.

• The following quote highlights some of the strikingly different social norms practiced by the Ismaili, in contrast to the Islamic orthodoxy. They practiced communism in their neighborhoods, and a sharing of people as well as property-

“The duty of Ulfa (union) – This duty consisted of assembling all their goods in one places and enjoying them in common without any one retaining any personal property which might give him an advantage over the others…Every man worked with diligence and emulation at his task in order to deserve high rank by the benefit he brought. The woman brought what she earned by weaving, the child brought wages for scaring away birds. Nobody among them owned anything beyond his sword and his arms…the missionaries [would then] assemble all the women on a certain night so that they might mix indiscriminately with all the men. This… was true mutual friendship and brotherhood.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 109-110.

• The Arabic language is a Semitic language, with its roots in the ancient and primitive lives of the Bedouin. As we know, these nomadic people had very little in the way of a written language but their oral traditions were very rich and descriptive, often poetic, and represented what was known in daily life – love, war, wine, the harsh desert environment. As the Arab Empire developed, grew and spread, Arabic as an imperial language began to change and expand to meet new cultural needs, and the Arabs brought their poetry to the people they conquered. Quoting author Bernard Lewis, their poetry was,

“…concrete, not abstract, though often subtle and allusive; rhetorical and declamatory, not intimate and personal; recitative and spasmodic, not epic and sustained; a literature where the impact of words and form counted for more than the transmission of ideas.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 131-132.

• Many languages spoken today have strong ties to Arabic, a carry over from Arab imperialism, even in places where the Empire might not have been fully extended. Swahili, Muslim Turkish, Urdu and Malay are all written in an Arabic script with strong Arabic vocabularies – comparable to the correlation between English and Greek and Latin.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 133.

• Historical Islamic civilization was rich with poetic language and a system of beliefs, but woven into its very fabric were also the concepts of state, law, art – and of course, religion as its most prominent feature. “Islam meant submission not only to the new faith, but to the community”. A separation of church and state was inconceivable. Early loyalties were to the community in Medina and the prophet Muhammad himself and later was extrapolated to the authority of the Empire and the Caliph. “Islam was at first Arab citizenship, later the first-class citizenship of the Empire.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 133.

• Shari’a is the Arabic word for the code, or holy law that was developed through a synthesis of the Qur’an and the teachings and traditions of Muhammad. Used as a code of conduct, Shari’a explained how the individual as well as society was expected to lead life. It was religious, political and social in its scope. Although a jurist might offer explanation or interpretation, in fact there was no “legislative” process or government branches – law came from God, so there was not much to be decided or debated. Second to God was the Caliph, who oversaw the military, religious and civil events making sure they adhered to the Shari’a. The Caliph had no powers to divine new laws or change existing ones.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 133-134.

• Much of Islamic religious literature was influenced by Christian and Jewish ideology in its early years. Elements if the Talmud, as well as Christian apocalyptic literature can be seen as incorporated into the Islamic “Tradition”. Jewish and Christian Syrians were often the translators for bringing texts into the Arabic world, in subjects such as astronomy, medicine and physics. These translations were encouraged and regular during the reign of the Abbasids.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 136-137.

• In art, the Arabs took the tradition of Greco-Roman art and architecture and added their own cultural elements to it. For example, because Islam is opposed to direct representation of the human image, art developed in forms of more geometric and stylized designs, feeding into what we think of as Byzantine art.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 138.

• Early Muslims did not proselytize or force their faith on people under their rule. There were often certain special taxes or limitations imposed on non-Muslim peoples, but, “Otherwise he left them their religious, economic and intellectual freedom, and the opportunity to make a notable contribution to his won civilization.” Ruling Muslims took pride in their ruling class and believed that those who did not “believe” would eventually be judged and burn in Hell, and it was not their place to usurp a divine destiny.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 140.

• Although developed later in the history of the culture, Arabic art and literature is lyrical and reflective of the religious beliefs and social structure. The following quote is from author Bernard Lewis-

“Arabic literature, devoid of epic or drama, achieves its effects by a series of separate observations or characterizations, minute and vivid, but fragmentary, linked by the subjective associations of author and reader, rarely by an overriding plan. The Arabic poem is a set of separate and detachable lines, strung pearls that are perfect in themselves, usually interchangeable. Arabic music is modal and rhythmic, developed by fantasy and variation, never by harmony. Arabic art – manly applied and decorative – is distinguished by its minuteness and perfection of detail rather than by composition or perspective. The historians and biographers, like the fictions writers, present their narrative as a series of loosely connected incidents.”

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 142.

• The 11th century saw the beginning of the decline of the Islamic Empire. In 945 Buwaihids, a Persian dynasty seized the Iraqi capital. Trade with China and Russia declined and then disappeared. Internal attacks weakened the Empire and external forces, coming to a head with the Christian crusades. In 970 the Seljuqs captured Baghdad from the Buwaihids, bringing Sunni Muslims as Grand Sultans to Iraq.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 145-147.

• Mongol invaders were next to invade Iraq, and they were in no way interested in Islam or any of the social structures it held in place. With the Mongol conquest came the collapse of the organized, centralized government and the destruction of the irrigation systems that had contributed to such agricultural success. The Turks in Cairo then controlled Egypt and Syria, bringing a feudal society back to the Arabs, and Baghdad was no longer an Arab center. The decline of the Arab Empire can then be summarized, according to the author, in three vital points-

1. The retransformation from a commercial economy back to a feudal one.

2. The loss of Arab political independence, as ruled by the Turks.

3. The change of the focal point of Arab society from Iraq to Egypt.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 154-159.

• As the dispersed Arabs continued to practice Islam to varying degrees in different locations throughout the Middle East, the West was developing and going through a renaissance of its own. Never cut off completely from European developments, the Arab world was slowly changed by developments such as the combustion engine (cars, trains, etc… replacing livestock for transportation) as well as the exploration and development of oil resources by Western interests.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 170-171.

• Arab nationalism found its roots in Syria in the early part of the 20th century, where modern press and publications were used to transmit ideas and propaganda, to promote ideas of unity and commonalties, as seen in Europe. In what would become Saudi Arabia, the highly restrictive and extremely traditional Islamic sect of the Wahhabi movement was established as the official creed for Abd al-Aziz Su’ud and the territory he and his warriors annexed. The British were responsible for creating new states in the Middle East, as barter for the assistance of Bedouins and Arabs against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War (including new divisions of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Trans-Jordan and Palestine.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, pp. 173-174.

• The First World War brought new stressors as well as new ideas to the Arab world. With both Allied and Axis forces fighting in their backyards, Arabs were often living side by side with Westerners, seeing the direct effects of the spread of education, changes in economy and challenging new ideas. These challenges were viewed as positive by some and devastating and threatening by others.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History, 1960, Harper and Row, NY, p. 177.

Summary by Rina Abrams.