Mystical Speculation

The search for the deeper meaning of received texts and traditions is a constant of religious communities, and the Christian majority and Jewish minority of medieval western Christendom were no exceptions. Within the Christian majority, numerous mystical and pietistic groups emerged. To an extent, the Roman Catholic Church was successful in absorbing many of these groups into its fold; some of these groups, however, seemed to cross the boundary into heterodoxy, giving rise to the perceived proliferation of heresy and the elaboration of repressive mechanisms for dealing with what was viewed as a dangerous threat. The same creative forces are evident in the Jewish world as well, where new interpretations of the biblical and rabbinic texts and traditions abounded as well.

In northern Europe, the most potent of these new tendencies was to be found in the Rhineland area, in a twelfth-century movement dubbed by modern scholarship Hasidei Ashkenaz (The German Pietists). This loose movement was headed by some of the most venerable and illustrious rabbinic families in the area. These thinkers advanced novel understandings of traditional biblical imagery, and their heretofore-unpublished writings are slowly being edited and analyzed. The pietistic teachings of this group have been far better known. The major repository of these teachings is the well-known Sefer Hasidim, a compilation of many literary forms, perhaps most prominently didactic tales with moral and ethical directives. These teachings generally take a radically negative view of surrounding Christian society, urging upon the pious believer extremes of self-abnegation.

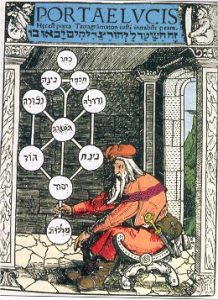

Mystical speculation was somewhat broader and more diversified across the southern areas of Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. These diverse mystical movements advanced alternative methods for plumbing the deep secrets of the universe, involving a variety of reinterpretations of traditional Jewish teachings and behaviors. With the passage of time, one mystical stream became increasingly prominent, that called loosely theosophic Kabbalah. This version of medieval Jewish mysticism posited a multi-faceted divinity, whose various sefirot or sectors interacted dynamically with one another and with the lower levels of the universe as well. As this tendency matured and achieved preeminence, its adherents produced the classic work of medieval Jewish mysticism, the Zohar.

Images

Primary Texts

Secondary Literature

- G. Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (3 rd ed.; New York- Schocken Books, 1956), 80-243.

- M. Idel, Kabbalah- New Perspectives (New Haven- Yale University Press, 1988).

- E. Wolfson, Through a Speculum that Shines- Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish Mysticism (Princeton- Princeton University Press, 1994).

- M. Idel, The Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia, trans. J. Chipman (Albany- SUNY Press, 1988).

- E. Wolfson. Abraham Abulafia—Kabbalist and Prophet- Hermeneutics, Theosophy, and Theurgy (Los Angeles- Cherub Press, 2000).

- A. Green, A Guide to the Zohar (Stanford- Stanford University Press, 2004).

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website