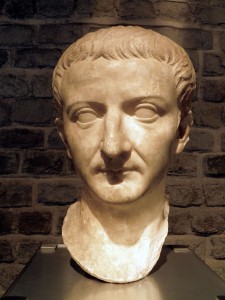

Tiberias Julius Alexander (e.g. nephew of the Jewish Philosopher, Philo)

Tiberias Julius Alexander (e.g. nephew of the Jewish Philosopher, Philo)

Tiberius had chosen an administrative career in the emperor’s service. Like everyone else, he had to begin by serving a term in the armed forces, before taking his first civil position in about 42 CE as the epistrategus of the Thebaid, governor of one of the three great regions into which the Roman province of Egypt was divided.

Nero placed the government of Egypt in the hands of Tiberius at the beginning of 66. In May, King Agrippa II (48 – 100 C.E.) came to Alexandria to congratulate him. Soon afterward, a Jewish uprising broke out in the city, which Tiberius mercilessly crushed. Josephus is our unique source for this episode in the history of Alexandrian Judaism.

Josephus, The Jewish War 2, 490-93; 494 – 97

On one occasion, when the Alexandrians were holding a public meeting on the subject of an embassy that they proposed to send to Nero, a large number of Jews flocked into the amphitheatre along with the Greeks; their adversaries, the instant they caught sight of them, raised shouts of “enemies” and “spies,” and then rushed forward to lay hands on them. The majority of the Jews took flight and scattered, but three of them were caught by the Alexandrians and dragged off to be burnt alive. Thereupon the whole Jewish colony rose to the rescue; first they hurled stones at the Greeks, and then snatching up torches rushed to the amphitheatre, threatening to consume the assembled citizens in flames to the last man. And they would have actually done this had not Tiberius Alexander, the governor of the city, curbed their fury. He first, however, attempted to recall them to reason without recourse to arms, quietly sending the principal citizens to them and entreating them to desist and not to provoke the Roman army to take action. But the rioters only ridiculed this exhortation and used abusive language of Tiberius.

Understanding then that nothing but the infliction of a severe lesson would quell the rebels, he let loose upon them the two Roman legions stationed in the city, together with two thousand soldiers, who by chance had just arrived from Libya to complete the ruin of the Jews; permission was given them not merely to kill the rioters but to plunder their property and burn down their houses. The troops, thereupon, rushed to the quarter of the city called “Delta,” where the Jews were concentrated, and executed their orders, but not without bloodshed on their own side; for the Jews closing their ranks and putting the best armed among their number in the front offered a prolonged resistance, but when once they gave way, wholesale carnage ensued. Death in every form was theirs; some were caught in the plain, others were driven into their houses, to which the Romans set fire after stripping them of their contents, there was no pity for infancy, no respect for years: all ages fell before their murderous career, until the whole district was deluged with blood and the heaps of corpses numbered fifty thousand; even the remnant would not have escaped, had they not sued for quarter.

Although the number of dead was most probably less than fifty thousand, the figure put forth by Josephus, the events of the year 66 C.E. were nonetheless a terrible trial for the Jews of Alexandria, as bad as the pogrom of 38 C.E., if not worse. The only Jews who escaped the general slaughter were the elders, the high ranking notables Tiberius took under his protection.

Source: Joseph Mélèze Modrzejewski. The Jews of Egypt. (p. 186 – 189)