Liturgy, Lore, Mysticism and Magic (3rd-7th century CE)

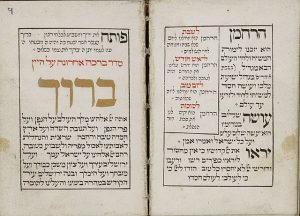

A jewish prayer book from Fürth, Bavaria, 1738

Jewish Liturgy

We cannot leave the discussion of the great literary heritage of Talmudic Judaism without discussing the development of Jewish liturgy and the eventual emergence of canonized prayer collections. Ultimately, it was the contribution of the rabbis that provided the raw material for the early medieval attempt to collect the prayers into texts which we call prayer books (Siddurim and Mahzorim).

Tannaitic and amoraic scholars made essential contributions to the development of Jewish liturgy, although it would be naive and simplistic to claim a controlling role for them. Jewish liturgy has its earliest roots in the individual prayers of the biblical period. We cannot know for sure whether prayer had a regular place in the Temple’s sacrificial ritual, but it is quite certain that individuals sometimes recited prayers while bringing sacrifices, and it is also true that in both Temples the levitical choir chanted psalms as an accompaniment to the sacrifices. Nonetheless, the prayers of individuals and the psalms of the choir did not constitute a fixed communal ritual or what we would describe as an organized worship service.

The Second Temple period offers the first evidence of fixed liturgical prayers. During this period the Jewish people was gradually turning toward prayer, and it was slowly becoming institutionalized even in the Temple. Indeed, various passages in the apocrypha, pseudepigrapha, and, especially, the Dead Sea Scrolls testify to the growth of fixed patterns of daily, Sabbath, and festival prayer among at least some Jews. As a result, when the Temple was destroyed in 70 C.E., and the sacrificial ritual ceased, Judaism was prepared to make the transition to prayer.

The destruction afforded the rabbis a unique opportunity to develop a liturgical system. Soon after the destruction, the tannaim at Yavneh began to standardize ritual practice. They began by fixing a definite list of benedictions for the Amidah prayer and, as well, by setting the times for prayer. The Amidah (literally “standing” prayer), also known as the Eighteen Benedictions, is the central part of every service, according to rabbinic practice. Further developments, regarding the recitation of the Shema (“Hear, 0 Israel,” Deut. 6-5, etc.), the Grace after Meals, and other benedictions, took place over the first two centuries C.E. Nonetheless, tannaitic sources preserve few actual liturgical texts because prayer remained so fluid in this formative period. It was during the amoraic period that the liturgy began taking on a more fixed nature.

No fixed prayer collections are known to have existed in talmudic times. Although there was a basic sequence of obligatory prayers, the text of the liturgy had not yet been standardized, but different versions of the various prayers were available and some of these had attained written form in private notes.

The liturgy was standardized much less quickly in Babylonia than in Palestine, where the patriarchate and the centralized academies made the process easier. The Jewish masses, especially in Babylonia, were sometimes not very receptive to the new liturgy being introduced by the sages. It took a long time to win their acceptance, and sometimes the rabbis had to fight against popular custom and superstition. In due course, however, forms of worship and liturgical texts became more and more standardized throughout the amoraic period.

Meanwhile, highly significant developments were taking place in Palestine. Alongside the statutory prayers instituted in tannaitic times, the tradition ofpiyyut (liturgical poetry) developed. Based in large part on midrashic teachings, this poetry sought to expand the traditional prayers for various occasions. The composers of piyyutim (liturgical poems) followed a longstanding pattern of literaryand poetic expansion of existing material. The new poetry, alongside the increasingly standardized prayer service, served as the model for the great liturgical collections of the gaonic period, which set the pattern for all future Jewish worship.

Excerpted from Lawrence H. Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991.

Overview

Primary Sources

-

- The Weekday Amidah- Themes of Jewish Prayer

- The Qedushah- The Mystical Praise of God

- A Qedushta by Yannai- On the Recitation of the Shema

- A Liturgical Poem for the Sabbath Preceding Passover- Miracles that Occurred at Night

- Babylonian Talmud Pesahim 56a- The Oneness of God and the Children of Israel

- Mishnah Hagigah 2-1- Teaching the Secrets of the Torah

- Jerusalem Talmud Hagigah 2-1 (77a)- Merkavah Speculation

- Jerusalem Talmud Haggigah 2-1 (77a-77c)- Four Who Entered the Pardes

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 33b- Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai and the Cave

- Sefer Yetzirah- The Early Kabbalah

- Ma’aseh Merkavah- A Mystical Prayer

- Horvat Kanaf Amulet- Incantation Against Fever and Pain

- Aramaic Magic Bowl- The Expulsion of Lilith

- Aramaic Magic Bowl- The Protection of the Family

Articles

- Judah Goldin. “The Magic of Magic and Superstition.” Aspects of Religious Propaganda in Judaism and Early Christianity. Ed. Elisabeth Schüssler-Fiorenza. Notre Dame- University of Notre Dame Press, 1976.

- Shinan, Avigdor. Synagogues in the Land of Israel- The Literature of the Ancient Synagogue and Synagogue Archaeology. Sacred Realm- The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World. Ed. Steven Fine. New York; Oxford – Oxford University Press, 1996.

Images

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website