In this selection, Josephus deems Jewish superiority in divine worship and Egyptian envy the causes of anti-Semitism. Josephus refutes the nonsensical stories of Egyptian historians who gave an account of the ancient presence of Jews in Egypt and the Exodus which was, in effect, an anti-Semitic myth.

In this selection, Josephus deems Jewish superiority in divine worship and Egyptian envy the causes of anti-Semitism. Josephus refutes the nonsensical stories of Egyptian historians who gave an account of the ancient presence of Jews in Egypt and the Exodus which was, in effect, an anti-Semitic myth.

(223) The Egyptians were the first who cast reproaches upon us. In order to please that nation, some others undertook to pervert the truth, so that they would neither admit that our forefathers came into Egypt from another country, as the fact was, nor give a true account of our departure from there.

(224) Indeed, the Egyptians took many occasions to hate us and envy us, in the first place because our ancestors had had dominion over their country and because of their prosperity when they were delivered from [the Egyptians]

and returned to their own country. Further, the difference of our religion from theirs has occasioned great enmity between us since our way of divine worship is as distant from that which their laws appointed as is the nature of God from that of brute beasts.

(225) For they all agree throughout the entire country to esteem such animals as gods although they differ from one another in the particular worship they pay to them. Certainly these men are entirely of vain and foolish minds, and have thus accustomed themselves from the beginning to have such incorrect notions concerning their gods, and could not think of imitating that decent form of divine worship which we practiced. However, when they saw our

institutions approved of by many others, they could not but envy us on that account.

(226) For some of them have proceeded to such a degree of folly and meanness in their conduct as not to hesitate to contradict their own ancient records, indeed, to contradict themselves also in their writings, and yet they were so blinded by their passions as not to discern it.

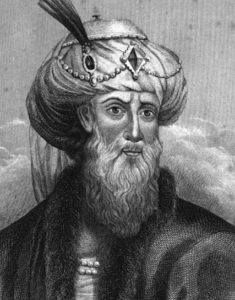

(227) And now I will turn my discourse to one of their principal writers whom I have a little earlier made use of as a witness to our antiquity;

(228) I mean Manetho. 112 He promised to interpret Egyptian history from their sacred writings, and began by stating that our people came into Egypt, many ten thousands in number, and subdued its inhabitants. Then he further confessed that we went out of that country afterward, settled in the country which is now called Judea, and there built Jerusalem and its Temple. Now thus far he followed his ancient records.

(229) But after this he permits himself, claiming to have written what rumors and reports circulated about the Jews, to introduce incredible tales, wishing to present us as mixed with the Egyptian multitude who had leprosy and other diseases and who were condemned to flee Egypt.

(230) He mentions Amenophis, a fictitious king’s name, though for that reason he would not set down the number of years of his reign which he had accurately done for the other kings he mentions. He then ascribes certain fabulous stories to this king, having presumably forgotten how he had already related that the departure of the shepherds for Jerusalem had been five hundred and eighteen years before….

(304) I shall now add to these accounts something about Lysimachus 113 who has taken up the same topic as those previously mentioned—the false story of the lepers and cripples—but has gone far beyond them in the incredible nature of his forgeries which plainly demonstrates that he contrived them out of his virulent hatred of our nation.

(305) His words are these- “The people of the Jews being leprous and scabby and subject to certain other kinds of diseases in the days of Bocchoris, king of Egypt, 114 fled to the temples, and got their food there by begging. As the numbers of those who had been afflicted with these diseases were very great, there arose a scarcity in Egypt.

(306) Thereupon Bocchoris, the king of Egypt, sent some to consult the oracle of Ammon 115 about this scarcity. “The god’s answer was this, that he must purge his temples of impure and impious men by expelling them out of those temples into desert places. But as to the scabby and leprous people, he must drown them and purge his temples, the sun being indignant that these men were allowed to live; and by this means the land will bring forth its fruits.

(307) Upon Bocchoris’s having received these oracles, he called for their priests and the attendants upon their altars and ordered them to make a collection of the impure people and to deliver them to the soldiers, to carry them away into the desert, but to take the leprous people, wrap them in sheets of lead, and let them down into the sea.

(308) Thereupon, the scabby and leprous people were drowned, and the rest were collected and sent into the desert in order to be exposed to destruction. There they assembled together, took counsel as to what they should do, and determined that, as the night was coming on, they should kindle fires and lamps and keep watch; that they also should fast the next night and propitiate the gods in order to obtain deliverance from them.

(309) On the next day, there was one, Moses, who advised them that they should venture upon a journey and go along one road till they should come to places fit for habitation. He charged them to have no kind regards for any man, nor to give good counsel to any, but always to advise them for the worst, and to overturn all those temples

and altars of the gods they should meet with.

(310) The rest agreed with what he had said and did what they had resolved to do, and so crossed the desert. The difficulties of the journey being over, they came to an inhabited country, and there they abused the population and plundered and burned their temples, and then came into that land which is called Judea where they built a city and dwelled therein.

(311) That city was named Hierosyla, 116 because of their robbing of the temples. After the success they had, they through the course of time changed its name, that it might not be a reproach to them, and called the city Hierosolyma (Jerusalem) and themselves Hierosolymites (Jerusalemites).”

112. Egyptian high priest, ca. 280 B.C.E., who wrote a history of Egypt from mythical times to 342 B.C.E.

113. An Alexandrian writer of uncertain date, but later than the 2nd century B.C.E.