In Muslim Tradition the Dome of the Rock Restored Solomon’s Temple

In Muslim Tradition the Dome of the Rock Restored Solomon’s Temple

In 638 C.E. Christian Jerusalem fell to a minor Arab officer by the name of Khalid ibn Thabit from the clan of Fahm. The patriarch of Jerusalem, Sophronius, had by then lost all hope of relief from Constantinople, since all the major cities of Syria (including Damascus) had opened their gates to the invading Muslim armies.

Most of these armies had already moved north or south, subjugating whatever remained of the Syrian and African provinces of the Byzantine empire. Caesarea alone refused to capitulate and was brought under siege, which cut it off from the Palestinian hinterland but not from marine lines of communication with the center of the empire in Constantinople. Soon, however, Caesarea would succumb to Muslim armies headed by Mu‘awiyah—an Arab aristocrat who belonged to the Umayyah family in Mecca and who, 20 years later, would become the first member of the Umayyad dynasty to rule the new Islamic empire.

Jerusalem, an isolated city on the edge of the Judean desert, might well have held out against the invading Arabs a little longer. The Arabs had spread themselves throughout the countryside and did not seem to have laid a proper siege upon the city, lacking the technical means or experience to besiege such a fortified settlement. Jerusalem of the early-seventh century—the holy heart of the Christian world, the focus of religious sentiments, pious aspirations, miraculous events and Biblical history—was a nearly impregnable bastion. It was a Late Antique Roman city with thick walls, scores of towers and imposing gates.

For whatever reason, the Christian patriarch of Jerusalem nonetheless decided to capitulate, but only a minor Arab commander was on hand to take charge of the holy city. Most Arab sources skip this aspect of the conquest of Jerusalem; the only reference to Sophronius’s somewhat anticlimactic surrender is recorded in a ninth-century description of the Islamic conquests.

History, it seems, willed that this particular account should remain in the shadows of the historical record.

Soon after Jerusalem was occupied by Muslims, it emerged in its full glory within Islamic religious thought and practice. Jerusalem quickly became the focus of extensive imperial building activity, transforming it from a predominantly Christian town into a holy Muslim city. Islamic traditions regarding the conquest were shaped and recorded at least a century after the actual event took place. By then, the Islamic holiness of Jerusalem was well established, and the city’s name had become forever attached to Islamic hagiography. It was inconceivable, therefore, that Islam’s first encounter with Jerusalem should be an ordinary event. Indeed, Jerusalem’s Muslim conquerors quickly realized the importance of the city, and many prominent Muslims wanted to take credit for this new and special jewel in the Islamic crown.

Of the many traditions that arose regarding the capture of Jerusalem, one in particular took precedence and eventually came to replace all others as the conquest’s “canonical report.” This tradition attributes the conquest of Jerusalem to Caliph ‘Umar (634–644 C.E.); it describes in great detail his taking of the city, which culminated with the caliph standing on the Temple Mount and establishing Jerusalem’s first mosque (which came to bear ‘Umar’s name) on the site. The choice of ‘Umar as the conqueror of Jerusalem and the builder of the first mosque marks the beginning of Jerusalem’s transformation into an Islamic holy place.

Jerusalem breathes messianism. Both Judaism and Christianity regard Jerusalem as the place where their messianic aspirations are to be fulfilled. For Jews, the messiah, a scion of the house of David, will establish his throne in Jerusalem, the capital city of their ancestor, renewing Jewish kingdom and freedom. For Christians, the messiah, also a son of David, will return to Jerusalem—the place of his passion, death and resurrection—to usher in the End of Days and the Millennial Age.

Islamic traditions about the conquest of Jerusalem are also imbued with messianism. Caliph ‘Umar is the most venerated figure in Islam after the prophet Muhammad himself. Biographies and other early sources emphasize the title of al-faruq bestowed on ‘Umar. The interpretation of this word in Arabic sources—“he who differentiates [farraqa] between right and wrong”—is already charged with the idea of divine choice. Also, the meaning of the word in its Aramaic origin is “savior” or “deliverer,” which is to say “messiah.” Islamic tradition therefore describes ‘Umar’s (the Savior’s) entrance into Jerusalem as a messianic event. Like Jesus, he reaches the city from the Mount of Olives and Gethsemane, enters through the eastern gate, then proceeds to the Temple Mount, discovers the place of Solomon’s Temple and restores worship at the ancient holy place by building a mosque.

Early in the seventh century, messianic ardor was in the air, and eschatological ideas were central to the Islamic message. The Prophet Muhammad emphasized that the Day of Judgment was at hand. Tradition tells us that Muhammad would lift two fingers, one pressed against the other, and say- “There is as much space between me and the Hour [of Judgment].” The Koran opens with praise to God, the “Lord of the Day of Judgment,” and is full of eschatological references and descriptions.

Once Jerusalem fell into Muslim hands, it was natural for the city to become associated with Islamic eschatological ideas and visions, for both Judaism and Christianity had long identified the city as the setting of both messianic events and the Last Judgment.

Jerusalem had been under Christian rule for 300 years. Christian holy places stood as the physical embodiment of Christian history, commemorating the life, passion, death, resurrection and ascension of Christ, as well as other events connected with the Virgin, the apostles and the early martyrs. Two Christian edifices in particular represented the early-seventh-century expectation that the Second Coming was close at hand- the complex of the Holy Sepulchre, the presumed place of Jesus’ burial, and the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives, the spot from which Jesus ascended into heaven. These two symbols of the death, resurrection and ascension of Christ—standing directly opposite one another—bolstered Christians’ faith that Jesus would soon establish the eternal divine order by returning to the place from which he had left earth.

Between the two lay the Temple Mount, which Jewish tradition identifies as Mount Moriah, where Abraham bound and nearly sacrificed his son Isaac. The Temple Mount was also the site of Herod’s Temple and probably Solomon’s Temple. When the Muslims arrived, however, the huge rectangular platform lay in desolation, mute testimony to Jesus’ prophecy- “Truly I tell you, not one stone will be left here upon another; all will be thrown down” (Matthew 24-2; Mark 13-2; Luke 21-6). For Christians, the desolation of the Temple Mount was proof that their faith had triumphed over Judaism.

The Muslims found Jerusalem throbbing with Christian piety. The Christian holiness of the city had physical manifestations- churches, basilicas, monasteries, pilgrims’ hostels, martyrions (structures raised over the tombs of Christian martyrs), chapels and scores of holy relics of various kinds. The faithful came to the city from all over the Christian world. In 630 C.E., after defeating the Persians, who had held the city for a brief period of 16 years, the Christian emperor Heraclius returned to Jerusalem with the Holy Cross, which the Persians had removed to their capital, Ctesiphon. The sight of a Christian emperor bringing the true symbol of the death and resurrection of Jesus back to Jerusalem was a momentous event, which only heightened the messianic expectations. Was it not time for the return of Christ himself, now that his cross was restored to his sepulchre? Jerusalem’s new Muslim conquerors understood the city’s intense holiness, and the eschatological visions of the Koran now found physical expression in this sacred city.

Although the Jerusalem conquered by the Muslim Arabs had been a Christian city for 300 years, underlying this physical space was a long-established Jewish tradition. Half a millennium had passed since Jews had been banished from Jerusalem by the Roman emperor Hadrian, but the signs of the Jewish presence had not been obliterated. One reason is that Christianity itself, though emphasizing the role of Jesus and the people who surrounded him, is steeped in the Old Testament and preserves the memory of its major personalities.

But there was more than that. The site of the Jewish Temple, though left in desolation since the Roman destruction, was nevertheless a space that could not be ignored. Its desolation did not only remind Christians of the success and truth of their religion- This spot, the site of Mount Moriah and the Jewish Temple, which would not be rebuilt until Jesus’ Second Coming, was nonetheless the site of the Jewish Temple. The Temple Mount was thus a sacred site, elevated above other sites. It was therefore not surprising that the Temple Mount, so intimately connected in tradition with such figures as Adam, Abraham, David and Solomon (the Muslims had no, or very little, knowledge about the Second Temple or Herod), appealed to Muslims when their ruler embarked upon reshaping Jerusalem as a Muslim holy place.

Mount Moriah and the unusual perforated rock on the top of it became the heart of this process of the Islamization of Jerusalem. It was from this point, for Muslims, that the holy took its shape.

In 1996 the distinguished Islamic scholar Oleg Grabar published a book called The Shape of the Holy- Early Islamic Jerusalem, which discusses the process by which Islam reshaped Christian Jerusalem into an Islamic holy city allied to Mecca and Medina, the two holy shrines of Islam in western Arabia. Grabar identifies the period in which the Islamization of Jerusalem occurred as beginning with the Muslim conquest and ending with the Crusader occupation—that is, between 638 C.E. and 1099. During this period Jerusalem came under the rule of several Muslim dynasties- the early years of the caliphate of Medina from 632 until 661 C.E.; the Umayyad caliphate from 661 until 750; Abbasid rule from Baghdad, which lasted from 750 to 878; and a series of rulers from Egypt, including the Tulunids, Ikhshids and Fatimids, between 878 and the arrival of Crusaders in 1099.

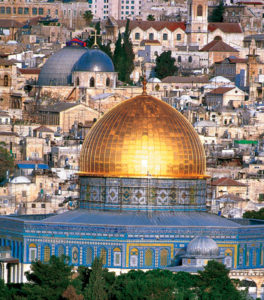

Of all these rulers, Grabar sees the Umayyads as the most important, and of all the Umayyad buildings, he rightly regards the Dome of the Rock as the most significant Muslim edifice in Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock, built by the Umayyad caliph ‘Abd al-Malik (685–705 C.E.) was essential in shaping the Islamic holiness of Jerusalem.

Grabar had been fascinated with the Dome of the Rock for more than 40 years. (His 1959 article, “The Umayyad Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem,” is still one of the best essays written on the subject.) Unlike other non-Muslim scholars, Grabar had the full cooperation of Muslim Waqf authorities and was allowed to examine many places on the Temple Mount (called the Haram al-Sharif, or “Noble Sanctuary,” by Muslims) that no non-Muslim today would be allowed to examine, let alone record in detail. Grabar was also fortunate to be working with a highly talented photographer, Said Nuseibeh, and the computer experts Muhammad al-Asad and Abeer Audeh, all of whom had free access to the Dome of the Rock, Al-Aqsa Mosque and every other place on the Temple Mount, whether above or below the ground. The fruits of this labor are evident in The Shape of the Holy as well as in The Dome of the Rock, which Grabar published with Said Nuseibeh (also in 1996).

The Dome of the Rock, which represents the Islamic reshaping of Jerusalem, was built a mere two generations after the Islamic conquest. It is universally regarded as one of the most beautiful and fascinating monuments of early Islam.

The building of the Dome of the Rock opposite the dome of the Holy Sepulchre Church, which for more than 300 years had towered over the desolate area of the Temple Mount, challenged the Christian dominance of the city. Built at a higher elevation than the Holy Sepulchre, the Dome of the Rock was a dazzlingly beautiful Islamic structure. According to the tenth-century Arab geographer Al-Muqaddasi, who lived in Jerusalem, many Arabs believed the Dome of the Rock was originally built to compete in beauty with the splendor of the churches, especially the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This, he added, would prevent Muslims from being enchanted by the Christian holy places.

But the Dome of the Rock did much more than that. Two inscriptions on copper plates over the eastern and southern gates of the structure carry clear messages- “The Unity of God and the Prophecy of Muhammad are true,” and “The Sonship of Jesus and the Trinity are false.”

This message repeats itself, sometimes in a shorter form, on all epigraphical material from the time of the Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik’s construction of the building onward—on coins, milestones and other building texts. Like many fashions that began in the court and were imitated by the public, this simple declaration of faith became fashionable as well. The text, “There is no God but Allah alone; he has no companion,” for example, was inscribed on gold and silver coins that were put into circulation around 696 C.E. At a Byzantine fortress called Rujm Sfar on a road from the Arabah to Beersheva, I found a stone inscribed with seventh- or early-eighth-century script reading “I, Yusuf ibn Zubayd al-Ayli, do not associate anything with Allah” (la ushriku bi allah shay‘an ).

The Dome of the Rock was more than a vehicle for the expression of anti-Christian policy, however. The choice of a dome on top of a circular structure surrounded by a double octagonal ambulatory was not accidental. This architectural shape was common in buildings of a commemorative nature (such as martyria). Grabar points out that the Dome of the Rock belongs to a class of buildings intended to make a statement, in this case to indicate the presence of Islam in full power and splendor, eclipsing both the Holy Sepulchre and the Nea (Justinian’s New Church of the Virgin). “It belonged to a relatively rare category of shrines, architectural compositions that seem more important by what they are than by what happens in them,” Grabar observes. The Dome of the Rock was not a mosque, it was a shrine, and it no doubt was built to honor and commemorate the rock over which the dome itself was raised.

What made the rock so important? Although most of the traditions regarding the rock were recorded after the building was constructed, they nonethless retain ancient memories. The most important memory involved the Jewish Temple built by Solomon; the Muslims believed the rock of the Dome of the Rock was a vestige of Solomon’s Temple.

There is sound reason to believe that soon after the Arab conquest, both Muslims and Jews (who could now return to, and live in, the city) worshiped at the rock around which the Jews had already developed annual pious rituals. Early in the fourth century, Jews were allowed to visit the Temple Mount (from which they had been barred since 135 C.E.) on the ninth day of the month of Ab (when both the First and the Second Temples had been destroyed, according to Jewish tradition) to lament the destruction of Jerusalem, the burning of the Temple and the loss of Jewish statehood. In the year 333 the so-called Bordeaux Pilgrim wrote-

Not far from the statue of Hadrian [erected on the Temple Mount within the complex of the Temple to Jupiter built by emperor Hadrian after the subjugation of the Second Jewish revolt in 135] there is a rock with a hole in it to which Jews come annually; they anoint it and tear their cloths, lamenting, and sobbing. And then they go away.

Some Christian sources say that when the Jews were allowed to visit the place of the ruined Temple during the Byzantine period, they would anoint the rock. This should not seem unusual from the viewpoint of Jewish customs, for anointing, as a sign of consecration, is a Biblical practice. In Exodus 40-9–16, for instance, God orders Moses to anoint the Tabernacle for the purpose of its consecration- “And thou shall take the anointing oil and anoint the tabernacle and all that is therein … Thus did Moses according to all that the Lord commanded him.” The consecration of any object or person involved the use of a special holy unguent. (See 1 Samuel 16-13 for the anointment of David as king of Israel.) The Hebrew word messiah means “the anointed,” as does the Greek word for “messiah”- christos, or Christ. So perhaps every year on the ninth of Ab, members of priestly families, joined by common pilgrims, would rub holy oil on the rock while others would recite from Psalms or Lamentations. The fact that the Jews could show the Muslims the place of the (Solomonic) Temple was of great importance for the Muslim rulers.

Many years ago I proposed that the Dome of the Rock was built by the early Muslims to symbolize the renewal of the Temple. The new holy structure thus served as a physical refutation of the Christian belief that the site should remain in desolation. Similarly, early Jewish midrash, though composed some 60 years after the building of the Dome of the Rock, hails the Muslims as the initiators of Israel’s redemption and praises one Muslim ruler as the builder of the “House of the Lord.”

A very elaborate Islamic tradition describes the Dome of the Rock as the Solomonic Temple. This tradition appears in the collection of traditions belonging to the literary genre known as “Praises of Jerusalem,” compiled early in the 11th century (more than 50 years before the First Crusade).

The Muslim scholar who compiled this tradition, a Jerusalem resident named al-Wasiti, describes in great detail the building of the Dome of the Rock and the various reasons for its erection. After stating that the Dome of the Rock was built on the site of Solomon’s Temple, he tells of the rituals that were performed in the structure. These rituals were completely alien to Islamic practice, but al-Wasiti reports them without any objection; indeed, he seems to have believed that they were perfectly appropriate for the edifice in which they were performed. The rituals involved the anointing of the rock with a special unguent (al-Wasiti describes in detail the composition and preparation of the unguent) and the burning of such large amounts of incense inside the edifice that thick smoke obscured the dome above. When the doors of the Dome of the Rock were opened, the fragrance of the incense reached the upper market of the city.

Immediately after describing the rituals performed in the Dome of the Rock, which are reminiscent of rituals performed in the Jewish Temple, al-Wasiti states that “the Rock was in the time of Solomon the son of David 12 cubits high and there was a Dome over it.” He then quotes another tradition-

It is written in the Tawrat [Bible]- “Be happy Jerusalem,” which is Bayt al-Maqdis [in Hebrew, Beit ha-Miqdash, or the Temple] and the Rock which is called Haykal [in Hebrew, Heikhal, meaning the Temple or Sanctuary; compare Psalms 27-4 and 65-5 (65-4 in English)].

The main activities at the Dome of the Rock took place on Mondays and Thursdays, which in Jewish tradition are days of special sacredness appropriate for peforming rituals. For example, the Law is read in public during the morning service on these days. Mondays and Thursdays are also days of fasting, and special supplications are added to the usual morning and afternoon prayers. The fact that special rituals alien to Islam were performed in the Dome of the Rock on these Jewish sacred days—rituals involving the anointing of the Rock, the lavish use of incense and the lighting of candles—connects this Islamic tradition with the service of the sons of Aaron the high priest in the Temple. The influence of ancient Jewish memories on this tradition is so profound that al-Wasiti quotes a Hebrew prayer—without knowing its exact translation—that he says was uttered in the Solomonic Temple (in Hebrew, barukh atta Adonay, or “blessed art thou the Lord”).

All this suggests that the building of the Dome of the Rock was meant to be an important statement of a political and religious nature.

According to Islamic tradition, immediately after the building of the Dome of the Rock, five Jewish families were employed to clean the place and prepare wicks for its lamps. It is difficult to imagine that the Jewish families who worked in the Dome of the Rock would have been simple street sweepers. More likely, they were Jews from priestly families who were honored with the task of serving in the holy Temple, even if that meant preparing wicks for candles and cleaning the Temple’s courts. They may well have felt themselves to be like the “righteous” described in the Psalms- “Planted in the House of the Lord, / they flourish in the courts of our God” (Psalm 92-14 [92-13 in English]).

In those days there was no Rabbinic prohibition preventing Jews from entering the sacred precincts of the Temple. That prohibition was not introduced until late in the Mamluk period, after the Crusades. The first mention of the prohibition comes in a letter sent from Jerusalem by Rabbi Obadia da Bartinoro to his father in 1488.

The shaping of the holiness of Jerusalem, and particularly the shaping of the holiness of the Temple Mount in the Islamic religious consciousness, was influenced by the Jewish and Christian traditions encountered by Muslims after their swift conquest of the Syrian provinces of the Byzantine empire. The Koran does not mention Jerusalem, and the Arabs who conquered it came to learn about its spiritual importance only after more intimate contact with Jews and Christians; they were then exposed to the Biblical accounts of the city and to the many traditions regarding Solomon’s Temple. Solomon is mentioned in the Koran; he is venerated as the wisest prophet of God. In that period of early Islam, however, Muslims knew little about the major Biblical figures who appear in the Koran, and they needed Jewish and Christian assistance to learn more about them.

The Jews contributed to the deep messianic feelings and expectations that had already existed among the Muslims—especially by encouraging the new conquerors, who had been regarded as heralding the final redemption of Israel, to renew worship on the Temple Mount. When the Dome of the Rock was built, the rituals performed in it were reminiscent of the rituals that had been performed in the Solomonic Temple- the anointing of the Rock, the burning of incense and the lighting of oil lamps on Monday and Thursday. These actions clearly indicate that the Muslims wanted to link themselves historically with Solomon, the great prophet-king. In doing so, they leapt back past Christianity—then their main enemy—and challenged the Christian idea that the Temple would remain desolate until Jesus’ Second Coming.

For the Jews, on the other hand, the Umayyad caliph who built the Dome of the Rock was the one “who repairs the breaches of the Temple.” For them, the Muslim occupation was the beginning of redemption.