When Israel’s first prime minister applied for membership at Kibbutz Sde Boker, he wasn’t automatically welcomed. The 18 young men and women who had pitched their tents in the desert a year earlier were far from unanimous in confirming membership upon the aging statesman, who was then 67. By a margin of only one vote, they received Ben-Gurion within their economically impoverished, highly idealistic ranks. In 1953, when he left his official post as head of state, he, too, began working the land.

When Israel’s first prime minister applied for membership at Kibbutz Sde Boker, he wasn’t automatically welcomed. The 18 young men and women who had pitched their tents in the desert a year earlier were far from unanimous in confirming membership upon the aging statesman, who was then 67. By a margin of only one vote, they received Ben-Gurion within their economically impoverished, highly idealistic ranks. In 1953, when he left his official post as head of state, he, too, began working the land.

Ben-Gurion was called back to the government just two years later, first as Defense Minister, then as Prime Minister. Upon his second resignation in 1963, he returned to Sde Boker and spent the rest of his life there, until his death a decade later. He requested in his will that his desert home be preserved exactly how he left it as a site open to the public. And a government-funded program did just that. But for years, all visitors could see was a small exhibit. Thanks to renovations conducted five years ago, his entire home is now open to visitors. And his former guards’ quarters now house an exhibition detailing the riveting biography of one of Israel’s historical giants.

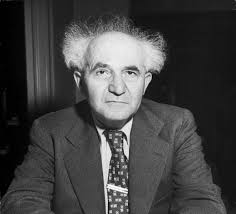

When he was 20 years old, David Green, a native of Plonsk, Poland (then Czarist Russia) made aliyah and changed his name to Ben-Gurion, or lion cub. As early as 1935, when, as chair of the Jewish Agency, he traveled through the desert on his way to Petra and Aqaba, he formulated view of the Negev. It is, he said, “a great Zionist asset with no substitute anywhere in the country.”

Although Ben-Gurion’s goal was to integrate as a regular member of Sde Boker, it soon became clear that he needed to work in a more controlled environment with less exposure to the elements and more security. The Defense Ministry constructed his simple “Swedish Hut,” which was large enough to house five kibbutz families. Its structure and furniture, nevertheless, display great simplicity and frugality. And the many gifts on display in the living room represent what was closest to his heart. There are pictures of the state’s official symbol–the seven branched menorah–and of his colleague Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a copy of Israel’s Declaration of Independence and a Chanukiah that plays Hatikva. A large globe is darkened where Israel is located. The spot formed from Ben-Gurion’s repeatedly showing guests Israel’s place in the world.

Other highlights include Ben-Gurion’s library/study, which contains 5,000 books. Even the Biblical quotations he kept on his desk remain. Most of them speak of the Negev’s blessings, such as these words from Isaiah 35-1. “The wilderness and the solitary place shall be glad; and the desert shall rejoice and blossom as the rose. It shall blossom abundantly, and rejoice even with joy and singing.”

The red felt, tarboosh (fez-like) hat Ben-Gurion wore while studying law in Turkey, a recording of the moment he declared independence and his signed order creating the Israel Defense Forces are among the fascinating artifacts displayed next door. Designed in a chronological fashion, the museum emphasizes Ben-Gurion’s embrace of the Biblical dream of reclaiming the desert and absorbing a huge influx of immigrants. “The cradle of our nation,” he called it. The exhibit reveals the character of Ben-Gurion as husband and father; his wide-spread correspondence with citizens of Israel and world Jewry. And his replies to children are exceptionally moving and without airs. “To my friends at Kibbutz Nachal Oz (Brook of Courage),” he wrote in 1961. “Anyone who has even a drop of pioneering spirit in his soul is celebrating the tenth anniversary of your settlement. I do not know if a brook flows by your kibbutz–but courage is not lacking. Remain firm in your determination and you shall succeed.”

A complete description of Ben-Gurion’s biography would fill volumes. One tidbit our tour guide shared with us is the whereabouts of the Ben-Gurions’ three children. Their eldest, Geula, died three years ago at age 80 in Tel Aviv. Their son Amos, who is now 81, lives in Haifa. Another daughter, Renana Ben-Gurion Leshem, in her late 70s, lives in Tel Aviv. And, like an entry in “Ripley’s Believe It or Not,” Amos’ son Alon, the only grandchild carrying the surname Ben-Gurion, works as the assistant director of food and beverage at the Waldorf-Astoria in Manhattan.

“He was a fascinating grandfather,” says Alon Ben-Gurion, 50, a former IDF paratrooper and a graduate of the Tel Aviv University and Cornell University. Alon recently received, as a gift from Konrad Adenauer’s grandson, a photograph of Ben-Gurion and Adenauer, the Chancellor of West Germany from 1949 to 1963, taken during a historic meeting at the Waldorf-Astoria. “The fact that he was a prime minister, there was no royalty attached to it. He was my grandfather. We didn’t look at him in terms of his being the head of the country,” Alon says. “He dressed very modestly, usually with khaki clothes. Food, entertainment, and all this was not on his agenda. One of the few movies he saw in public, I saw with him. It was the gala premiere of “Exodus” in Tel Aviv. He was devoted to one thing. And that was the state of Israel.”