Megiddo was one of the most important cities in Canaan and Israel in the biblical period. It was at Megiddo that the Canaanite city-states gathered to rebel against Egyptian domination. According to the Bible, Joshua captured Megiddo (Josh. 12-21) and King Solomon built up Megiddo (1 Kings 9-15). In 732 BCE it was captured by the Assyrian King Tiglath-pileser III and served as an Assyrian province. The Book of Revelations (16-16) places the battle of the last days at Armageddon (Megiddo).

A village had been established on the hill of Megiddo at the end of the 6th millennium BCE, but the first fortified urban settlement, remains of which were uncovered on bedrock in the eastern part of the tel, dates from the beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE. Within its walls was an elongated rectangular temple, with an altar opposite its entrance; it had a low ceiling, supported by wooden columns place on stone bases. The renewed excavations have exposed several long, parallel stone walls, each 4 m. thick, the lanes between them filled with the bones of sacrificed animals.

At the end of the 3rd millennium BCE, a circular bama (altar) of fieldstones, 8.5 m. in diameter and 1.5 m high, was built. Seven steps led to its top, upon which sacrifices were offered. This is an excellent example of the cultic bamot (altars) frequently mentioned in the Bible.

They answered them and said, “He is; see, he is ahead of you. Hurry now, for he has come into the city today, for the people have a sacrifice on the high place today. “As soon as you enter the city you will find him before he goes up to the high place to eat, for the people will not eat until he comes, because he must bless the sacrifice; afterward those who are invited will eat. Now therefore, go up for you will find him at once.” So they went up to the city. As they came into the city, behold, Samuel was coming out toward them to go up to the high place.

–I Samuel 9-12-14

Geva, Hillel, Archaeological Sites in Israel, No. 6. Jerusalem- Israel Information Center, 2000.

The Stables

“So king Solomon was king over all Israel (1 Kings 4-1) and Solomon had 40,000 stalls of horses for his chariots, and 12,000 horsemen” (1 Kings 4-26).

“And Solomon built…all the cities of store…and cities for his chariots and cities for his horsemen” (1 Kings 9-17-19)

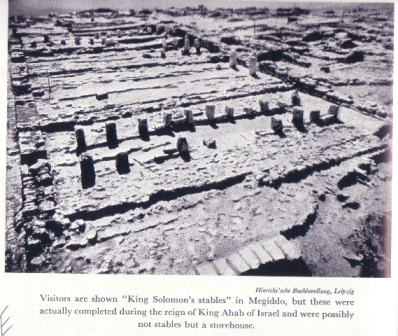

The archaeologists’ astonishment grew with every new structure which came to light. They found that several large stables were always grouped round a courtyard, which was laid with beaten limestone mortar. A 10-foot wide passage ran down the middle of each stable. It was roughly paved to prevent the horses from slipping. On each side, behind the stone stumps, lay roomy stalls, each of which was exactly 10 feet wide. Many of them had still remains of feeding troughs and parts of the watering arrangements were still recognisable. Even for present day circumstances they were veritable luxury stables. Judging by the extraordinary care which had been lavished on buildings and services, horses in those days were at a premium. At all events they were better looked after than were human beings.

When the whole establishment was uncovered, Guy counted single stalls for at least 450 horses and sheds for 150 Chariots. A gigantic royal stable indeed. “And this is the reason of the levy which king Solomon raised- for to build… the wall of Jerusalem and Razor and Megiddo…” (1 Kings 9-15). “And Solomon gathered together chariots and horsemen- and he had a thousand and four hundred chariots and twelve thousand horsemen, whom he bestowed in the cities for chariots…” (1 Kings 10-26). In view of the size of the royal stable at Megiddo and the stables and chariot sheds of similar type which have been found at Tell el-Hesi, at Taanach and also at Jerusalem, the Biblical references must be regarded as mere hints at the reality. These tremendous results of the excavations give us a clear conception of the lavishness to which old Israel was accustomed in its imperial days.

Just as it was with Solomon’s copper mines, of which the Bible makes no mention, so it is with the no less famous “Solomon’s stables” in Megiddo. The opinion has become more widely accepted that they date not from Solomon’s time but from that of King Ahab of Israel (c. 875 to 852 B.C.), who according to the Assyrian account of the Battle of Qarqar (c. 854 B.C.) assembled 2,000 chariots, the largest force of war-chariots in the anti-Assyrian alliance. And so, basically the Biblical story has once more been confirmed, for we read (1 Kings 9-15) merely that Solomon fortified Megiddo and not that he built stables there and that, speaking generally, he had “chariots and horsemen” (1 Kings 10-26), but not that they were garrisoned in Megiddo.

It remains merely to add that in the view of a number of experts, among them the Israeli specialist in Biblical archaeology, Professor Yohanan Aharoni of Tel Aviv, what are reputed to be “Solomon’s stables” not only date from the time of Ahab but also are not stables. It seems they are storehouses for supplies. Similar buildings destined for the same purpose have been excavated by Yohanan Aharoni in Beersheba.

Werner Keller. The Bible as History. Bantam Books. New York. 1982. p.217-221.

Battle of Megiddo

After the death of Ashurbanipal, when the hated Assyrian colossus was shaken by the first signs of ultimate collapse, King Josiah had without hesitation banned the practice of foreign religions in Jerusalem. There was more to that than merely religious objections. It clearly signified the termination of the state of vassalage, of which the gods of Nineveh, imported by compulsion, were symbolic. Together with these compulsory deities, Josiah expelled all the Mesopotamian “workers with familiar spirits, and the wizards, and the images and the idols” (2 Kings 23-24). He also cleared out all the Canaanite religious practices (2 Kings 23-7).

Josiah’s reforms paved the way for a renewed religious and national vitality which developed into a regular frenzy when news of the fall of Nineveh confirmed their freedom.

Meantime something quite unexpected happened which threatened to ruin everything…. “Pharaoh-Nechoh king of Egypt went up against the king of Assyria to the river Euphrates- and king Josiah went against him, and he slew him at Megiddo, when he had seen him” (2 Kings 23-29). This passage from the Bible is a perfect example of how a single word can completely change the meaning of a narrative. In this case the wrong use of the little word “against” brands Josiah as the accomplice of the hated tyrant. At some point or other the word translated “against” has been wrongly copied. In reality Pharaoh Necho went to the aid of Assyria, i.e., “towards.” It was only through a chance discovery that the Assyriologist C. I. Gadd found out this historical slip of the pen.

The place of discovery was quite outside the normal archaeological pattern — it was a museum. In 1923 Gadd was translating badly damaged fragment of cuneiform text in the British Museum which had been dug up in Mesopotamia many years previously.

It read as follows- “In the month of Du’uz [June-July] the king of Assyria procured a large Egyptian army and marched against Harran to conquer it…. Till the month of Ulul [August-September] he fought against the city but accomplished nothing.”

The “large Egyptian army” was the forces of Pharaoh Necho.

After the fall of Nineveh what remained of the Assyrian forces had retreated to Northern Mesopotamia. Their king embarked upon the forlorn hope of reconquering from there what he had lost. It was for this purpose that Pharaoh Necho had hastened to his aid. But when after two months of fighting not even the town of Harran had been recaptured, Necho retired.

It was the appearance of Egyptian troops in Palestine that decided Josiah to prevent the Egyptians at all costs from rendering military aid to the hated Assyrians. So it came about that the little army of Judah marched against the far superior Egyptian force, with the tragic ending at Megiddo. “Neko,” writes Herodotus, “also defeated the Syrians43 in a land engagement at Magdolus.”

On the way back to Egypt Pharaoh Necho assumed the role of overlord of Syria and Palestine. He made an example of Judah, so as to leave it in no doubt on whom the country now depended. Jehoahaz, Josiah’s son and successor, was stripped of his royal dignities and taken as a prisoner to the Nile (2 Kings 23-31-34). In his stead Necho placed another son of Josiah upon the throne, Eliakim, whose name he changed to Jehoiakim (2 Kings 23-34).

Werner Keller. The Bible as History. Bantam Books. New York. 1982. p.298-299.

See also-

- The Megiddo Expedition

- Back to Megiddo, Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, BAR 20-01, Jan-Feb 1994.

- King Solomon’s Stables—Still at Megiddo? Graham I. Davies, BAR 20-01, Jan-Feb 1994.

- Horned Altar from Megiddo, 1000-900 BCE

- Bronze Soldier from Megiddo

- Shoshenq Megiddo Fragment

- Akeptous Inscription, 3-4th century CE