While Secretary of State Alexander Haig was on his way to Jerusalem in part to heal the rift between Israel and the United States, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger seemed to be working toward the opposite end.

While Secretary of State Alexander Haig was on his way to Jerusalem in part to heal the rift between Israel and the United States, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger seemed to be working toward the opposite end.

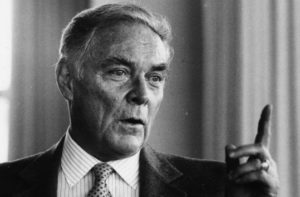

Weinberger charged in a Cable News Network television interview that it was Israel which cancelled the strategic cooperation agreement with the U.S. even though the U.S. had announced it was suspending the agreement in reaction to Israel’s extension of its civilian rule to the Golan Heights.

This was followed by a story in the Baltimore Sun last Tuesday that the Defense Secretary would be visiting Saudi Arabia and possibly Oman in February but not Israel in an apparent “snub” to demonstrate Weinberger’s anger over Israel’s action on the Golan.

Pentagon spokesman Henry Catto immediately stressed that Weinberger had accepted a Saudi invitation and “Israel has never been considered as part of the itinerary for this particular trip.” He said the Defense Secretary “does plan to go to Israel this year.” Nachman Shai, the Israel Embassy’s spokesman, also denied that Israel felt any snub. He said Weinberger is expected to go to Israel sometime this year.

While this may be true, the original implication that Weinberger was demonstrating his displeasure with Israel by not going to the Jewish State after visiting Saudi Arabia did nothing toward healing the rift between the Reagan Administration and the always sensitive Israelis.

“Good Guy,” “Bad Guy”

This situation, with Haig appearing as the “good guy” in relation to Israel and Weinberger as the “bad guy,” is nothing new for the Reagan Administration which begins its second year on January 20. Of course, the Administration has been under constant attack for speaking publicly with divergent voices not only on the Middle East, but on most crucial foreign policy issues.

But it is on the Israel-Arab relations that this split has been most public. It was Weinberger who, over Haig’s opposition, pushed through the sale of the five AWACS last year. After Israel’s destruction of Iraq’s nuclear plant and the bombing of terrorists’ headquarters in Beirut, it was Weinberger who sought an even harsher U.S. reaction than the temporary suspension of the delivery of F-15 and F-16 fighter planes to Israel.

Weinberger also seemed less than enthusiastic about the strategic cooperation agreement worked out between President Reagan and Israeli Premier Menachem Begin during Begin’s visit to Washington last September. In fact, when the memorandum of understanding was signed in November by Weinberger and Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, the ceremony was not held at the Pentagon, where the two defense officials held hours of talks, but at the National Geographic Society building without any press photographers present.

Although it was the State Department that announced the U.S. was suspending the strategic agreement over Israel’s action on the Golan, the Pentagon has been much harsher in its criticism. On December 20, only hours after Begin had strongly attacked the U.S. for its decision, Haig, Weinberger and Edwin Meese, counsellor to the President, all appeared on separate Sunday television interview programs. All stressed the continuing U.S. friendship toward Israel.

Haig, as he did after the Iraqi and Beirut bombings, stressed that it was the task of American diplomacy to work with Israel to “repair the damage” and “not exacerbate” the problems between Israel and the U.S.

Weinberger, however, did just that by accusing Israel of violating both the “spirit and the letter” of United Nations Security Council Resolution 242. He said the U.S. has to “bring home to the world” that the “cost” of actions such as the Golan annexation and Israel’s bombing of the Iraqi nuclear reactor cannot be condoned.

Explanations For Weinberger’s Behavior

Some people looking for explanations for Weinberger’s apparent anti-Israel attitude note that he came to the Pentagon from being general counsel and vice president of the Bechtel Group Inc., the San Francisco construction company that does millions of dollars of work in Saudi Arabia.

While there may be some validity to this, others attribute Weinberger’s attitude on the Middle East and other foreign policy issues to his previous service in government as finance director for Reagan when he was Governor of California and director of the Office of Management and Budget and then Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare under President Nixon, with no experience in foreign affairs or defense policy. Weinberger has apparently accepted the military establishment’s view of the world.

Specifically, he appears to accept the view that the U.S. must depend more on Saudi Arabia, “tilting” toward the Saudis in the hopes they will allow the U.S. to establish permanent bases in the desert kingdom, replacing those lost when the Shah of Iran, was deposed.

This is a forelorn hope, as William Quandt, the Mideast expert on the National Security Council during the Carter Administration, points out in a study published recently by the Brookings Institution. “U.S. military planners invariably fantasize about the merits of bases in Saudi Arabia,” Quandt wrote. “Politically, the Saudis are likely to continue to refuse, arguing that it could be politically destabilizing and that it would serve as a magnet to draw more Soviet forces in the area.”

Attitude Of William Clark

As the Reagan Administration begins its second year, much of the course of its policy toward Israel will depend on the attitude of William Clark, the President’s new National Security Advisor. Clark replaces Richard Allen, who was widely regarded within the Jewish community as a strong supporter of Israel.

Clark’s position on Israel is largely unknown. Except for some harsh words about Israel after the Beirut bombing, he has not spoken about the Middle East during his term as Deputy Secretary of State. In fact, he came to the State Department without any knowledge about foreign affairs. But since then he has won respect in the Administration and in Congress as a conciliator and organizer. Perhaps more important, unlike Allen, Clark will have direct access to Reagan, and unlike Haig, but like Weinberger, he is a California friend of the President.