Background

The Second Temple period, or Second Commonwealth, began in 538 BCE with a declaration by Cyrus the Great, king of Persia and Media, that the Jews could return to the Land of Israel and rebuild their Temple. The Temple and the city of Jerusalem were rebuilt by the year 515 BCE, and, in contrast to the First Commonwealth, the high priest became the secular as well as religious authority. This system of government lasted into the Hasmonean period and became an object of protest in the Dead Sea Scrolls, as well as in other literature of the period.

Hellenism

Another target for the protest of the Qumran sect was the influence of Hellenism, the synthesis of Greek culture with the native culture. The Greek city-state (polis) was the center for Hellenistic culture. It was here that the schools, theaters, and gymnasia were built. Greek language, literature, architecture, and philosophy were promoted in the city-states and were popular amongst natives of the Near East.

Hellenistic influence over Palestine began even before Alexander’s conquest. In the fourteenth century BCE, Palestine was influenced by the Aegean culture. During the Persian period (539–332 BCE), this influence became more extensive, including the use of Greek coinage in Palestine.

Hellenistic culture was perceived as a threat to traditional Jewish life. It mainly affected the urban Jews who came into daily contact with Hellenistic influences. The peasants, in contrast, continued to lead a Jewish cultural life, and the primary influence of Hellenism was in the addition of Greek words to their vocabulary. Jews who lived in the cities found themselves replacing Hebrew with Greek in order to be understood. They were influenced by the culture, literature, and architecture of Hellenism. Aristocratic families with ties to the priesthood tended to be more Hellenized, apparently as a result of their increased contact with the Hellenistic world. Some Jews even moved to the Greek cities known as the Decapolis where the dominant culture was Hellenistic.

The Hellenistic culture was a pagan one, and this was antithetical to the Jewish religion, which was strictly monotheistic. In order to justify the pagan worship of Hellenism, some Jews chose to radically reinterpret the Bible so that it would not contradict their new practices. In the late second century BCE, these types of Jews took control of the priesthood and tried to convert Jerusalem to a Greek polis. This incident was one of the causes of the Maccabean Revolt.

Ptolemies and Seleucids

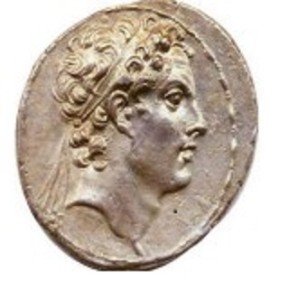

After the death of Alexander the Great, his empire was divided by his generals. Palestine was claimed by both Ptolemy (king of Egypt) and Seleucus (king of Syria). At the end of a protracted military struggle in which the land changed hands five times, Ptolemy won control of the area in 301 BCE.

During the years of fighting over Palestine, the area itself remained virtually autonomous, and outside influences—including Hellenism—were weakened. After Ptolemy took control of the region, Hellenistic influence increased. The Ptolemies maintained army posts throughout the country in the third century BCE, as the Seleucids were still trying to wrest control and five battles were fought in Palestine. Military colonies were established which later became Greek cities; Greek soldiers married Jewish women. Jews were also subject to the bureaucratic system developed by the Ptolemies for taxation and other governmental functions.

In 201 BCE, Palestine was conquered by the Seleucid king Antiochus III, who allowed Jews to live according to their religion. By then, Hellenism was firmly entrenched in Palestine.

The Maccabean Revolt (168–164 BCE)

When Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 BCE) ascended the Seleucid throne, he sold the office of high priest to the highest bidder. This had traditionally been a hereditary position of great religious importance and the Jewish population was greatly angered by the change. The new high priest, Jason, planned to establish a gymnasium and Hellenistic school in Jerusalem, with the intention of turning the city into a Greek polis.

Antiochus IV abolished the right to live according to the Torah and declared that the Jews were to live under the law of a Greek city. Some factions amongst the Jewish population were in favor of these new laws as they granted the Jews certain privileges, including citizenship in a Greek city, trade with other such cities, the minting of coins, and other advantages particularly attractive to the wealthy and powerful.

At the time, the rituals in the Temple continued according to Jewish law; however, eventually foreign deities were introduced into the Temple, too. Some even viewed the Israelite God as just another manifestation of the Greek god Zeus.

Antiochus became aware of stirrings of rebellion amongst the more pious Jews and in order to prevent a revolution he implemented persecutions which struck at the heart of Jewish culture. Idolatrous worship and cultic prostitution were introduced in the Temple; the Sabbath and festivals were outlawed. Unclean animals were offered for sacrifice on altars outside the Temple, circumcision and observing the Jewish dietary laws were forbidden. Transgressing the king’s new laws was punishable by death.

Antiochus’ attempt to stem the tide of rebellion had the reverse effect. Pious Jews rallied around the Hasmonean family (Judah the Maccabee and his brothers John, Simon, Eleazar, and Jonathan) who led an army against the Seleucids. The Maccabean army defeated the Seleucid generals and recaptured Jerusalem in 164 BCE. On the 25th of Kislev, the Maccabees rededicated the Temple, purifying it of all pagan worship and restoring the traditional rituals, a victory commemorated by the holiday of Hanukkah. Although the persecutions had ended, the war continued throughout the Land of Israel, as the Maccabees attempted to eliminate Hellenistic influences from the rest of the country.

Judah the Maccabee was killed in battle and his brother Jonathan took his place; the post of high priest remained vacant. Meanwhile, a civil war broke out in Syria for control over the Seleucid Empire. Jonathan gave his backing to Alexander Balas in exchange for the position of high priest. On Sukkot (the Festival of Tabernacles) of the year 152 BCE, Jonathan appeared in the Temple wearing the robes of the high priest. Thus began the Hasmonean dynasty which ruled the Jewish people until Palestine was conquered by the Romans in 63 CE.

Hasmonean Control of the Temple

The Maccabean revolt brought about a radical change in the high priesthood. Prior to the revolt, the high priests had belonged to the family of Zadokite priests (the sons of Zadok). As many of these priests had cooperated with the Hellenists, the family lost its command of the Temple in the aftermath of the revolt; the Hasmonean family took control.

The Zadokite priests (also known as the Sadducees) resented the new situation. They were embittered by their loss of power. Josephus and various Talmudic sources attest to the fact that the Pharisees were the most powerful group at this time; the Sadducees objected to the changes made in Temple practice under their influence.

Jewish Sects

During the period in which the Dead Sea Scrolls were composed, Josephus Flavius wrote of three major sects of Judaism—the Pharisees, the Sadducees, and the Essenes. For our purposes, a sect is defined as a group of people holding a particular religious ideology. The sects in the Second Temple period all believed in the Torah as the ultimate source of Jewish law, but differed on theological questions such as the nature of God’s revelation, the free will of human beings, and reward and punishment. They also disagreed as to how much Hellenistic influence was acceptable.

The biggest bone of contention between the sects was how to conduct Temple ritual. The Pharisees and Sadducees, the two major sects, fought bitterly over control of the Temple, with each group maintaining that the other’s sacrifices were invalid.

Sadducees

The Sadducees as a group can be traced back to approximately 150 BCE. As mentioned previously, they were connected to the priestly families and were mostly aristocratic. They were committed to the Jewish religion but also highly influenced by Hellenistic culture. They were named for Zadok, who had been the high priest in the Temple in Solomon’s time. Zadokites held the post of high priest throughout the First Temple period and in the Second Temple, until the Hasmoneans took over. The prophet Ezekiel prophesied that they would serve in the rebuilt Temple (44-9–16).

The Sadducees rejected the “traditions of the fathers” which were so fundamental to Pharisaic theology. Later rabbinic sources describe them as rejecting the concept of Oral Law. The church fathers maintained that the Sadducees accepted only the Torah and rejected the rest of the biblical corpus, but there is no evidence to support this claim. Modern scholars have followed the claim of the later rabbinic sources, but not all of the views of the Sadducees can be explained as rejections of Oral Law.

The Mishnah records a number of differences between the Sadducees and the Pharisees. The Sadducees held a person liable for damage done by his servant, while the Pharisees only required him to compensate for damage done by his animals (Exodus 21-32, 35–36; Mishnah Yadayim 4-7). The Pharisees and Sadducees disagreed on when to put a false witness to death- The Sadducees believed that he should be put to death only if the accused had been executed as a result of the testimony, while the Pharisees held that he should be executed only if the accused had not yet been put to death (Deuteronomy 19-19–21; Mishnah Makkot 1-6). The Sadducees believed that the purity laws were primarily laws pertaining to the Temple, while the Pharisees extended them to all aspects of daily life. As a result, the Pharisees viewed Sadducean women as impure due to the way they interpreted menstrual impurity laws; the Sadducees accused the Pharisees of inconsistency.

The primary dispute between the Pharisees and the Sadducees was on the subject of the timing of the Omer sacrifice. The Pharisees believed that the Omer was to be brought on the second day of Passover, while the Sadducees believe that “the morrow of the Sabbath” (Leviticus 23-11) meant the day after the Sabbath, i.e. Sunday. (According to the Pharisees, the Sabbath refers to the festival.) In order to support this interpretation, the Sadducees adopted a calendar which ensured that the holiday of Shavuot fell on a Sunday every year. This calendar, which was also used by the Qumran sect and the Book of Jubilees, was based on both the solar months and the solar years. The Pharisees used the biblical calendar, which was based on lunar months.

The Sadducees also differed from the Pharisees on matters of theology. For instance, they did not believe in reward and punishment after death nor did they believe in the immortality of the soul. They also did not believe in supernatural angels, although they must have believed in the “divine messengers” which appear in the Bible. They denied the belief that God controlled human affairs; rather, they believed in complete free will.

The Boethusians were a sect closely allied to the Sadducees. Most scholars maintain that the Boethusians originated with Simeon ben Boethus, whom Herod appointed high priest in 24 BCE. There is no proof for this, however. Parallels between some Boethusian rulings and the Dead Sea Scrolls indicate that the Boethusian sect pre-dates the Herodian period. Although the Boethusians disagreed on some points with the Sadducees, they seem to have been a sub-group of the sect.

After the Maccabean revolt, a small group of Sadducees left Jerusalem because they were unable to tolerate the Hasmonean takeover of the Temple. They retreated to Qumran and formed a faction which eventually became the Dead Sea sect.

Other moderately Hellenized Sadducees remained in Jerusalem. They supported the Hasmonean priest-kings and joined with the Pharisees in the governing council. They dominated the council during the reigns of John Hyrcanus and Alexander Janneus. The next ruler, Salome Alexandra, maintained thorough Pharisaic rule, but the Sadducees regained power in the Herodian era. A group of Sadducean priests made the pivotal decision to end the daily sacrifices, triggering the full-scale revolt against the Romans in 66 CE.

As a result of the Great Revolt and the destruction of the Temple, the Sadducees lost their power base—the Jerusalem Temple—and their strict legal rulings augured poorly for the adaptation of Judaism to the new surroundings and circumstances of the years ahead. Their traditions influenced the Dead Sea sect and the later Karaite sect, which became prominent in the eighth century.

Pharisees

The name Pharisees comes from the Hebrew, perushim, meaning separate. This most probably refers to the sect’s separation from ritually impure foods and those who ate them. The name may have been a pejorative term invented by their adversaries.

The Talmud describes two groups- haverim (associates), who did not eat ritually impure food even outside the Temple, and am ha-’aretz (people of the land), who were not scrupulous regarding Levitical purity and tithes. It is assumed that the haverim were the Pharisees, although the sources never associate the terms. The Pharisees were also called “the sages,” but this is a misnomer based on the Rabbis’ self-perception as the continuers of Pharisaic tradition.

The first mention of the Pharisees occurs in sources written during the reign of Jonathan the Hasmonean (about 150 BCE). Many scholars have identified the Pharisees with the Hasidim, a pious group which participated in the Maccabean Revolt. However, information about the Hasidim is too limited to make a positive identification. According to rabbinic sources, the Pharisees dated back even farther, to the Persian and Early Hellenistic periods, when the Men of the Great Assembly led the people. Although it is not possible to ascertain when the movement began, it is known that the movement achieved prominence in the Hasmonean period.

As the Hasmoneans became more Hellenized, the Pharisees became more politically active in opposing them. The Pharisees were in open warfare with Alexander Janneus, leading to his defeat by the Seleucid king in 88 BCE and a subsequent reconciliation. This story is recorded in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Pharisees were disagreed amongst themselves as to how to respond to the Hellenistic rulers. Some advocated supporting the government as long as it allowed them to practice Judaism according to their views. Others felt that only a Pharisaic government was acceptable and maintained that only a revolt would lead to that goal. The dispute was a central theme in the two revolts against Rome.

The Pharisees had a number of defining characteristics. Three chief characteristics of members of the group were-

1. They were members of the middle and lower classes.

2. They were only slightly influenced by Hellenistic culture.

3. They accepted the “traditions of the fathers”—nonbiblical laws and customs believed to have been passed down through the generations. These laws were part of the Oral Torah, which the Pharisees were experts in interpreting.

The Pharisees’ principal beliefs included the immortality of the soul, reward and punishment after death, and the existence of angels. The group believed in the existence of divine providence and felt that free will was not absolute, as God had a role in control of human affairs. Obviously, these beliefs strongly contradicted those of the Sadducees.

Later rabbinic sources maintain that the rituals in the Jerusalem Temple were practiced according to Pharisaic tradition. Some scholars have suggested that this represents a reshaping of history, developed after the Sadducees had disappeared and Jewish tradition began following the Pharisaic views. However, the Dead Sea Scrolls—specifically the Halakhic Letter—describe practices in the Temple attributed to the Pharisees in the Mishnah.

Josephus repeatedly stressed the Pharisees’ popularity among the people. Although Josephus was biased towards the Pharisees, his extensive firsthand knowledge of the period makes this a fairly reliable claim. This popularity is what gave the Pharisees the ability to lead the people after the destruction of the Temple, laying the groundwork for Rabbinic Judaism.

Essenes

Philo, Josephus, and Pliny the Elder described a third sect called the Essenes—Essenoi or Essaioi in Greek. No scholarly consensus has been reached as to the etymology of the name. According to Josephus and Philo, the sect numbered approximately 4,000. The Dead Sea Scrolls do not mention the Essenes by name, but most scholars identify the Dead Sea sect with the Essenes. One of their strongest arguments for this claim is Pliny’s mention of an Essene settlement between Jericho and Ein Gedi, the vicinity of Qumran. Nonetheless, the identification of the Essenes with the Qumran sect is not conclusive.

Membership in the Essene sect was not easy to achieve, even for the children of sectarians. Only male adults could join. Applicants were given three items—a hatchet, a loincloth, and a white garment—and had to undergo an initiation process which lasted for one year. At the end of the year, applicants were eligible for ritual ablutions. Two years later they were initiated by oaths (although in all other cases the Essenes forbid swearing). Once they were full-fledged members of the sect they were permitted to participate in communal meals.

The Essenes practiced community of property. New members relinquished all of their property, and all property was shared. The members worked in various occupations such as agriculture and crafts (avoiding commerce and weapon-making). The income from these endeavors was used to support the entire community and donated to charities around the country.

The Essenes believed in living simply. They dressed in simple white clothing and ate simple foods. Some Essenes were celibate, although in many cases celibacy was only undertaken after having had children. As the sect disagreed with the methods of sacrifice and observance of purity in the Temple, it did not participate directly in the Temple rituals, but instead sent voluntary offerings to Jerusalem.

A day in the life of an Essene began with prayer. After working at their occupations, the members assembled for ritual purification. The communal meal—prepared by the priest—was served to each member in order of status; all members wore special garments for meals. The members then returned to work, after which they assembled for another meal. Prayers were recited again at sunset. Though some of these practices were common to other Jews of the period as well, the Essenes’ unique manner of practice separated them from their fellow Jews.

The Essenes placed special emphasis on ritual purity. Members purified themselves before meals, after relieving themselves, and after coming into contact with non-members. They were meticulous about attending to natural functions modestly. The Essenes were also stringent in their observance of the Sabbath.

The sect believed in the concept of unalterable destiny and in the immortality of the soul. According to Josephus, their theology closely resembled that of the Pharisees.

Josephus also reported that the Essenes participated in the revolt against Rome in 66–73 CE and that some members were tortured by the Romans. In the aftermath of the failure of the Great Revolt, the Essenes disappeared.

The Dead Sea sect also disappeared after the destruction of the Temple. Now, after almost two thousand years of silence, its writings have been rediscovered. How can they help us understand the period of the Second Commonwealth and the events leading up to the destruction? What can we learn from these texts about the sect itself?

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

- Judaism, Hellenism and Sectarianism, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Hellenism as a Cultural Phenomenon, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Hellenistic Trends in Palestinian Judaism, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- The Maccabean Revolt, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Hasmonean Takeover of the Temple, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Jewish Sects in the Aftermath of the Maccabean Revolt, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Pharisees, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Pharisees and Sadducees, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- The Sadducees, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Essenes, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Sectarianism in the Second Commonwealth, Lawrence Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991.

- Jewish Sectarianism in Second Temple Times, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Great Schisms in Jewish History (Ed. Raphael Jospe and Stanley M. Wagner), Ktav, New York 1981.

- Hellenism in Palestine as a Cultural Force and its Influence on the Jews, Martin Hengel, Judaism and Hellenism, Fortress Press, Philadelphia 1974.

- The Feast of the Hanukkah, Roland de Vaux, Ancient Israel, McGraw-Hill, New York 1961.

- The Reasons for Sectarianism According to the Tannaim and Josephus’s Allegations of the Impurity of Oil for the Essenes, Meir Bar-Ilan.

- The Significance of Yavneh- Pharisees, Rabbis, and the End of Jewish Sectarianism, Shaye J.D. Cohen, Hebrew Union College Annual 55.

- Temple and Desert- On Religion and State in Second Temple Period Judaea, Michael Schwartz, Studies in the Jewish Background of Christianity, Mohr, Tubingen 1992.

- Karaites and Karaism, Jewish Encyclopedia.

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website