Babylonian Jewry (586 BCE-7th century CE)

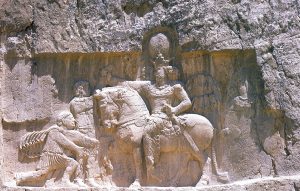

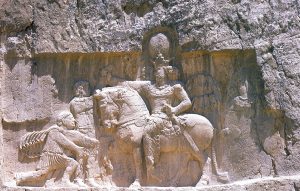

Shapur II Relief

The Early History of Babylonian Jewry

Shapur II Relief

From the accounts in Ezra and Nehemiah it is certain that only a small minority of Babylonian Jewry returned to rebuild the Land of Israel. The Murashu Tablets, the records of a prominent family of Babylonian bankers which mention numerous Jews, are usually taken as evidence of Jewish business activity in Nippur during the reigns of Artaxerxes I (465/4–424 B.C.E.) and Darius II (423–404 B.C.E.). That Jews attained positions of importance is indicated by the biblical account of Nehemiah, who was a high official of the Persian king, and this state of affairs provides the backdrop for the books of Esther and Daniel.

After Alexander’s conquest of Babylon in 331 B.C.E., Mesopotamia was ruled by the Seleucids for some two centuries. They soon founded new cities, which, together with the garrisons they established, fostered the Hellenization of Babylonia. We have no evidence regarding the effects of this process on the Jewish communities. The privileges accorded to the Jews by the Persians were reconfirmed by the new rulers. In the late third century B.C.E. Jews serving in the Seleucid army were excused from certain duties for religious reasons. One heritage of the Seleucid period in Babylonia was the use of the Seleucid era as a means of counting years (taking 312 B.C.E. as the year 1), a pattern that some Jewish communities continued well into the Middle Ages.

By 129 B.C.E. the decline of Seleucid power made possible the westward expansion of the Parthians (Parthia is located east and north of the Caspian Sea), and Babylonia now came under Parthian rule. The Parthian Empire allowed the native populations to continue their indigenous traditions, leaving the Greek colonies intact and granting favorable treatment to the Jews. Some contacts between the Parthians and the Hasmonean rulers of Palestine must have occurred. We know that in 41/40 B.C.E. the Parthians deposed Herod and supported the Hasmonean Judah Antigonus, only to be chased back across the Euphrates by the Romans in 38 B.C.E.

Little is known of the position of the Jews in the Parthian Empire during the Hellenistic period, but the evidence indicates that the majority of them were farmers and tradesmen with a small upper class of nobility. Attachment to the Land of Israel, especially to Jerusalem, and pilgrimage to the Temple are attested. From the story of the conversion to Judaism (ca. 40 C.E.) of the royal house of Adiabene, a Parthian vassal state in the upper Tigris region, we gather that Jews and Judaism were a regular part of Mesopotamian culture and life in this period. There was even a short-lived Jewish state in Babylonia from about 20 to 35 C.E.

By the Rivers of Babylon

The Jewish dispersion in Mesopotamia dates from the Assyrian conquest of the kingdom of Israel in 722 B.C.E. The mass deportations which followed brought Jews to the region of northern Mesopotamia. When the Babylonians conquered the kingdom of Judah and deported many of its people to Babylonia in central Mesopotamia in 597 and 586 B.C.E., the new exiles linked up with their brethren, and the Mesopotamian Jewish community began its climb to eventual ascendancy. It is most likely that the exiles from Israel moved south into Babylonia where the new exiles from Judah had been settled. When the Achaemenid Persians under Cyrus the Great conquered Mesopotamia in the sixth century B.C.E. and allowed the Jews to return to their homeland, only a small percentage took advantage of the invitation, and thus the Babylonian Jewish community continued to grow. In 331 B.C.E. Babylonia was conquered by Alexander the Great.

When it passed to the Seleucids on his death in 323, the Jews were granted a renewal of the privileges and freedoms proclaimed by Cyrus and some even served in the Seleucid armies. Yet the Jews of Mesopotamia must have been affected by the Hellenization policy pursued by the Seleucids in an effort to strengthen their hold on the land. They were certainly affected financially by the shift of the Seleucid Empire’s commercial center from Babylon to the newly founded city of Seleucia on the Tigris River. Their fortunes must have declined further during the Maccabean uprising of 168–164 B.C.E. and the ensuing period of tension during which the Hasmonean dynasty established itself.

From 171 B.C.E., the Parthians, an Iranian people, under the Arsacid dynasty, began to pressure the Seleucids in Mesopotamia. Under Mithradates II, they conquered the area in 120 B.C.E. The Jews were treated well by the Parthians, who also maintained good relations with the Hasmoneans. The Parthians attempted to influence events in Palestine by supporting Antigonus in his bid for the high priesthood in 40–39 B.C.E., but Herod soon regained control.

The limited sources at our disposal tell us about the exploits of a few distinguished Babylonian Jews who played a role in the Parthian nobility and dressed and behaved like members of this class. Little is known about the common people, however. From 20 to 35 B.C.E. there was a short-lived Jewish principality in Babylonia. Some Jews made pilgrimages to Jerusalem, though, and the royal family of Adiabene converted to Judaism in about 40 C.E. and then offered sacrifices at the Jerusalem Temple.

During the Great Revolt of 66–73 C.E. and the Bar Kokhba Revolt of 132–35 C.E., some Jews in Babylonia gave financial support to the rebel forces, and a few went to Palestine to fight the Romans. When Trajan invaded the Parthian Empire in 114–117 C.E., the Jews joined in the resistance against him at the very same time that their brethren in the Greco-Roman dispersion were engaged in the Diaspora Revolt. Both Palestinian and Babylonian Jews are reported to have been active in the silk trade, which was, no doubt, interrupted by these disturbances.

Pre-70 C.E. Pharisaism had little impact, if any, in Babylonia, and only two Pharisaic sages are known to have lived there, at Nisibis and Nehardea. After the Bar Kokhba Revolt several Pharisaic rabbinic sages fled to Babylonia, where they established centers that trained Babylonian tannaim. A mechanism for centralized rule over Babylonian Jewry had certainly come into being by the mid-second century C.E., yet the title resh galuta (exilarch) first appears only for Huna 1 (170–210 C.E.). In Parthian times, the sons of the exilarchs were sent to study in the Land of Israel. At the same time, the exilarchs sought to staff their courts with Palestinian-trained scholars who would not be dependent on local Jewish noblemen.

The Arsacid dynasty of the Parthians fell in 226 C.E. to the Sassanians. This dynasty sought to rule more directly, through an extensive bureaucracy, and, having originated as a priestly family, was dedicated to the cult of Ohrmazd, Anahita, and other divinities. Its governmental policies were intended to advance the Mazdean religion, a form of Zoroastrianism. Thus the reign of Ardashir I (224–241 C.E.) was a difficult period for all other religious groups, including the Jews. This period saw a temporary suspension of Jewish self-government. There are also some reports of anti-Semitic decrees. All this changed with the ascent of Shapur I in 242 C.E. He granted tolerance and freedom to all religious groups. By pacifying his own citizens, he hoped to strengthen his empire for war against Rome in the west. In any case, he was hailed enthusiastically by the Jewish community of Babylonia.

In 262–263 C.E. the Palmyran king invaded Babylonia, destroying some Jewish settlements, but Shapur I quickly restored order. It is probable that during his reign arrangements regarding the exilarchate and Jewish self-government were renegotiated and that a modus vivendi was reached between Jewish needs and the administrative system of the Sassanian Empire.

A series of short-term monarchs ruled from 272 to 292 C.E. This was a period of religious persecution for all non Mazdeans. Yet Jews appear to have been treated better than Manichaeans (a Persian religious cult) and Christians. The persecutions came to an end under Narseh (293–301 C.E.). Although some minor persecutions may have taken place early in the reign of Shapur II (309–79 C.E.), while he was still a child, we hear of no such disturbances for the remainder of his reign. Yet this was a period in which Christians were persecuted. When Julian the Apostate invaded Babylonia in 363, a number of Jewish communities were attacked by his armies. Some Jews, who supported Julian because of his plan to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, were massacred by the Persians.

Little is known about the reigns of Yezdegerd I (397–417) and Bahram V (420–38). Yezdegerd II (438–57) renewed the persecution of the Jews. He was followed by his son Firuz (459–86), who further intensified the persecutions. In his reign Jews are reported to have been massacred and their children given to Mazdeans. The exilarch Huna V was killed by the king. From 468 to 474 synagogues were destroyed, and Torah study was prohibited. Jews were again persecuted in the reign of Kovad I (488–531 C.E.), who had adopted the doctrines of Mazdak (founder of Mazdakism, a Zoroastrian offshoot, around the end of the fifth century) regarding community of property and women, which, of course, were rejected.

In 520 the exilarch Mar Zutra II was killed after establishing a short-lived independent Jewish principality at Mahoza. Much less is known of the period leading up to the Arab conquest. Jews fared well under Chosroes (531–78) but were persecuted again under Hormizd IV (579–80). Calm again prevailed under Chosroes Parwez (590–628). When the Arabs conquered Mesopotamia in 634 C.E. they were well received by the Jews and a completely new chapter in Jewish history was opened.

It is against this background that the efforts of the amoraim of Babylonia must be seen. Despite the constant ups and down of political and economic conditions, the rabbis labored on to study, collect, and redact amoraic traditions. When the Babylonian Talmud finally emerged from this process, it is no wonder that this great classic reflected in many ways the strange ambivalence of Jewish life in Babylonia. Here Jews could be a stable and respected part of society one day and a persecuted enemy the next. Yet no matter what, the study of the Torah continued and flourished.

Excerpted from Lawrence H. Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991.

Overview

Primary Sources

- Josephus, Antiquities XX, 17-95- The Conversion of the House of Adiabene

- Josephus, Antiquities XVIII, 310-79- A Jewish Babylonian Principali

- Jerusalem Talmud Yevamot 12-1 (12c)- The Tannaitic Movement in Babylonia

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 32b- The Great Tannaitic Sages

- Mishnah Yevamot 16-7- The Tannaitic Tradition in Babylonia

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website