Babylonian Captivity, 586-537 BCE

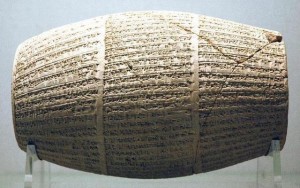

Nabonidus Cylinder

Like the Northern Kingdom of Israel, the Southern Kingdom of Judah, too, had come to an end. Both had been caught in similar predicaments- how to negotiate the treacherous diplomatic waters of a small power caught between two international superpowers on either side of it. Both small kingdoms had succeeded for a while at picking which power to side with and recognizing when it was best to simply subjugate itself to one or other of the neighboring empires. But neither Israel nor Judah could keep up the political balancing act forever and each, in turn, suffered defeat and devastation from the superpower to the north. The Davidic royal line had come to an end and, perhaps more traumatic, the Jerusalem Temple, the center of worship, was in ruins. What would eventually emerge from the Babylonian destruction would be a new political entity and a religion that had acquired, by the bitter waters of exile, a universalist, monotheistic outlook.

The Babylonian exile was not a demographic disaster for ancient Judah. 2 Kings 25-12 says that “some of the poorest of the land” were left behind to work the land; scholars today estimate that “some” actually represented 90% of the population and that only the elite were exiled.

While in Babylonia, the exiled people of Judah maintained their hope that the Davidic dynasty would be restored and that the Temple service would be restored. Their treatment in Babylonia was relatively benign—they seem to have been settled in abandoned cities and allowed to build houses for themselves and to cultivate land—and in fact prospered there. The Book of Ezra mentions contributions of gold and silver when the Temple was later rebuilt in Jerusalem and even refers to people who returned from exile owning slaves.

The head of the community in Babylonia was the Davidic monarch Jehoiachin. In 561 B.C.E. Nebuchadnezzar’s successor Amel-Marduk, released Jehoiachin from prison and even assigned him provisions from the royal storehouses.

The only manifestations of religion among the Jews in Babylonia that we know of were public prayer and communal fasts to commemorate the various stages of Jerusalem’s fall. The prayers, however, did not take place in buildings but rather outdoors, often near water. Hence the poignant words of Psalm 137- “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion.”

Though the Jews in Babylonia were able to maintain their ethnic and religious identity, there are indications that a process of assimilation had begun. A sixth-century B.C.E. seal reads, “Belonging to Yehoyishma, daughter of Sawas-sar-usur.” The “Yeho” in daughter’s name, in good Judean tradition, contains a part of the name Yahweh, while the father’s name is Babylonian and means “Shamash [the Babylonian sun-god], protect the king!” Even such leaders of the Jewish community as Sheshbazzar and Zerubbabel, later governors of Judah, had Babylonian names.

Excerpted from Biblical History: Jeremiah, Ezra and Esther, c. 586-330 BCE, Steven Feldman, COJS.

Artifacts

Images

Articles

Maps

Videos

Websites

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website