The Aleppo Codex is a full manuscript of the entire Bible, which was written in about 930. For more than a thousand years, the manuscript was preserved in its entirety in important Jewish communities in the Near East- Tiberias, Jerusalem, Egypt, and in the city of Aleppo in Syria. However, in 1947, after the United Nations Resolution establishing the State of Israel, it was damaged in riots that broke out in Syria. At first people thought that it had been completely destroyed. Later, however, it turned out that most of the manuscript had been saved and kept in a secret hiding place. In 1958, the Aleppo Codex was smuggled out of Syria to Jerusalem and delivered to the President of the State of Israel, Yitzhaq Ben Zvi.

Once the Aleppo Codex reached Israel, precise study of it began in many areas. Scholars of the Masora and of the text of the Bible took note of its special status among the manuscripts related to it. It was found that the match between the spelling of the Aleppo Codex and the comments of the Masora was excellent, far better than the match of other manuscripts. Similarly, the vocalization signs in the Aleppo Codex were examined and described, along with the cantillation marks, the system of ge’iyot (a kind of accent mark), and the apparatus of the Masora. All of these terms will be explained and demonstrated in this site.

In Egypt, the Aleppo Codex was redeemed by the local Jewish community and entrusted to the synagogue of the Jerusalem Jews in old Cairo. According to tradition- and in the opinion of the biblical scholar and linguist, Moshe Goshen-Gottstein- the renowned Jewish philosopher and rabbinic authority, Maimonides (1138-1204), relied on the Aleppo Codex when he formulated the laws of Torah scrolls. As he wrote in his great legal code, Mishneh Torah- “In these matters we relied upon the codex, now in Egypt, which contains the twenty four books [of the Hebrew Bible], and which had been in Jerusalem for several years. It was used as the standard text in the correction of books. Everyone relied on it, because it had been corrected by Ben Asher himself, who worked on its details closely for many years and corrected it many times whenever it was being copied. And I relied upon it in the Torah scroll that I wrote according to Jewish law” (Sefer Ahavah, Laws of Torah Scrolls 8-4). Maimonides’ praise of the Aleppo Codex further enhanced the prestige of the venerated manuscript.

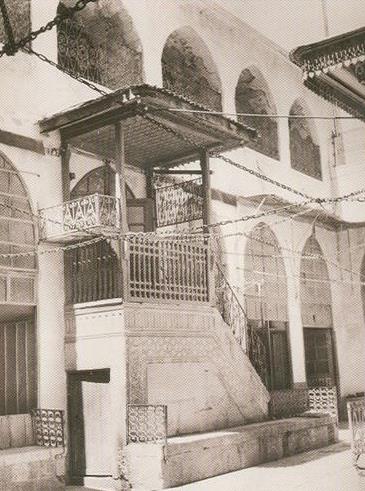

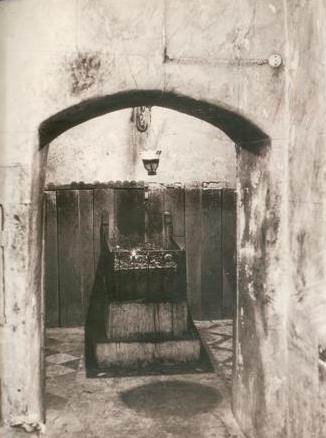

At the end of the 14th century, perhaps in 1375, the Aleppo Codex was brought from Egypt to the Syrian city of Aleppo (known as Aram Tzova in Hebrew) by a descendant of Maimonides named David bar Yehoshua. The venerated book was placed in the “Cave of Elijah” in the ancient synagogue, in a metal chest sealed with a double lock, far from the prying eyes of strangers. The Jews of Aleppo considered it their most important manuscript (we know of three other codices or ketarim in their possession, one of which is known as the “Small Keter”). So sacred did they consider this book that they used it to swear in religious judges, and believed it had magical properties. According to the inscription on its opening page-“Sacred to the Lord […] It shall be neither sold nor redeemed forever and ever […] Blessed be he who guards it, accursed be he who steals it, and accursed be he who mortgages it [. . .]” it was strictly forbidden to sell it or even just remove it from the synagogue. Violation of this injunction, they believed, would bring calamity upon the community.

Despite the secrecy surrounding it, or perhaps for that very reason, the fame of the Aleppo Codex spread far and wide, and generations of scribes made “pilgrimages” to consult it, seeking authoritative answers to textual questions. In 1559, Rabbi Joseph Caro, author of the renowned legal code Shulhan Arukh, sent a copy of the Codex from Safed to Rabbi Moses Isserles (the “Rema”) in Cracow, who used it to write his own Torah scroll. We know as well of Yishai ben Amram Hacohen Amadi of Kurdistan, who visited Aleppo at the end of the 15th century; Moshe Yehoshua Kimhi, who traveled to Aleppo on the instructions of his father-in-law, Rabbi Shalom Shakhna Yellin (1790-1874), a renowned scribe; and Professor Umberto Cassuto, whom the Aleppo community permitted to consult the Codex in 1943, prior to the publication of a critical edition of the Bible by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Not only Jews were fascinated by the celebrated manuscript. Some time before 1753, a British traveler named Alexander Russell was permitted to view the Aleppo Codex; a facsimile of one page of the Codex appears on the title page of a book by the scholar William Wickes (1877); and in 1910 a missionary named J. Segall published a photographic reproduction of two pages of the manuscript-those containing the Ten Commandments-in his book Travels through Northern Syria.

This glorious history came to an end on December I. 1947, two days after the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution to partition Palestine and establish a Jewish state, when riots against Jews and their synagogues broke out across the Arab world. The ancient Aleppo synagogue was destroyed, and it was rumored that the Aleppo Codex kept there had been desecrated and burned. Professor Cassuto wrote in the Haaretz daily paper on January 2, 1948- “If the news published in the press is indeed true, the famous Hebrew Bible that was the pride of the Jewish community of Aleppo, the very Bible which, according to tradition, Maimonides himself used, was burned in the course of the riots that broke out against the Jews of Aleppo a few weeks ago. Keter Aram Tzova, as it was called, is no more.”

Adolfo Roitman. The Bible in the Shrine of the Book- From the Dead Sea Scrolls to the Aleppo Codex. The Israel Museum, 2006. pp. 62-64.

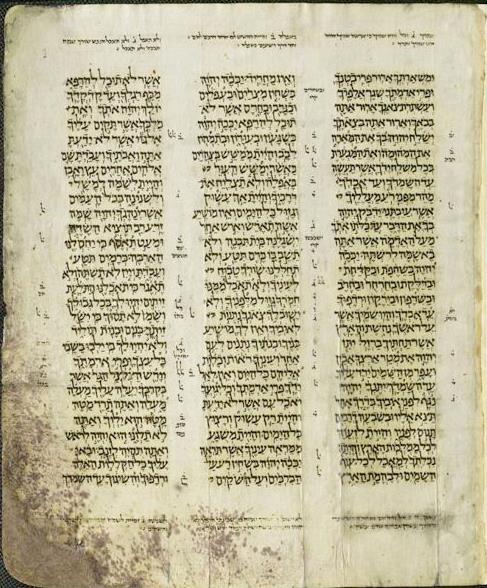

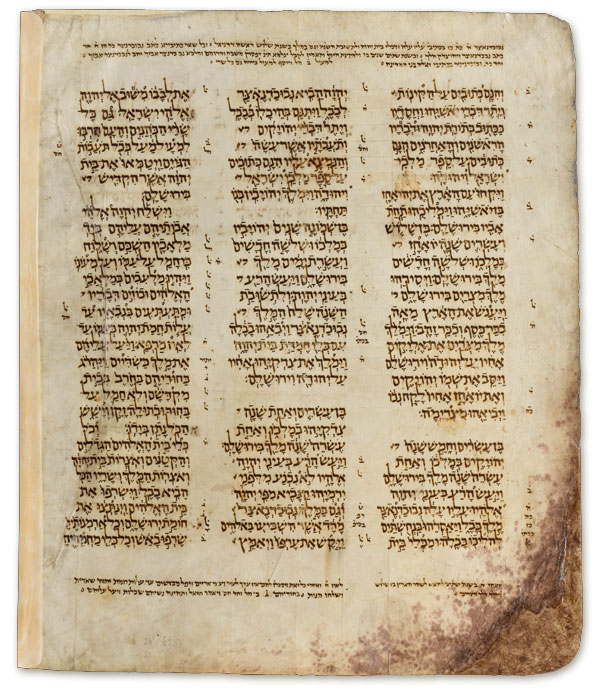

2 Chronicles 35-17-36-19 in the Aleppo Codex

On display here is a single page (with the text of 2 Chronicles 35-17-36-19) that had been separated from the manuscript; it was discovered by accident in New York in 1981 and entrusted to the Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem.

Blue and White Pages

Documenting the History of Israel

October 10, 2008 – February 2009

Israel Museum

See also-