Life in Ashkenaz

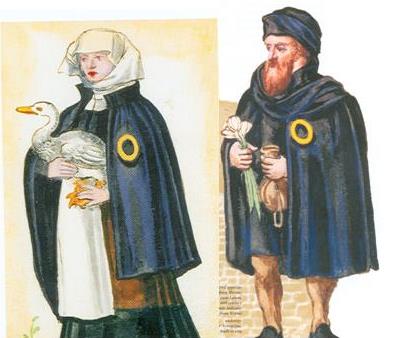

Jewish man and woman from Worms, illustrations by Markus zum Lamm, 16th century. The bulb of garlic in his hands indicates that the Jewish man is from Worms.

Jewish trading families had settled along the trade routes of the Rhine. Any new settlement was welcome to the secular and religious rulers, for every field that was cultivated, every house that was filled with life, every market place that developed into a city enhanced their renown and signified progress. Compared with other population groups, Jews often had skills and experience at their disposal which proved invaluable, for instance in setting up a state administration and expanding the trade sector.

Jewish boys had been learning how to read Hebrew from time immemorial in obedience of the divine commandment to study the Torah, while the majority of the Christians continued to remain illiterate for centuries. The Talmud-with all its stories about resolving arguments and breaking the law, about sizes and weights, compensation and defraudation, decrease in value and remuneration-not only instructed them in the ways of the world, but also imparted valuable skills for trade and business.

The ruling princes were quite happy to make use of these skills. Jews were highly esteemed both as doctors and as foreign merchants and seafarers who came close to holding a monopoly over Mediterranean trade in the 8th and 9th centuries, providing the royal and bishopric palaces with jewels, spices, perfumes, and other luxury goods. Their services as teachers and advisors were sought after, as well- the story of the merchant Isaak of Narbonne, whom Charlemagne entrusted in 797 with a Christian legation, is legendary; his task was to lead them to Baghdad to the court of the caliph Harun ar-Rashid as a guide well-versed in both language and geography. Isaak was the only one not to perish from the strain of the journey, and five years later he returned to Aachen with an elephant by the name of Abulabaz, a gift from the caliph.

Under Charlemagne, king of the Franks and, from the year 800 on, the first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, numerous Jewish communities were founded, and trade and the arts boomed. It was the era of royal Jewish safeguarding- Jews were placed on even legal footing with the Christians regarding economic questions. They were in charge of their own property, traded free of tax and restrictions, and were not discriminated against in court. The Jewish religion was expressly approved and compulsory baptisms prohibited, as was any attempt to prevent the Jews from fulfilling their religious precepts. This peaceful phase, characterized by prosperity and inspiration, proceeded until the time of the Ottonians, although no evidence exists of continuous Jewish settlements until the 10th century in the German Empire. Jewish life is mentioned again for the first time in a document of Otto the Great from the year 965- “Judei et cetera mercatores,” Jews and other merchants, are granted the privilege of trading in all wares and the permission to bring them into the country tax-free. This phrase made clear to what extent “Jews” and “merchants” had become synonymous. It expresses respect, referring as it does to the contribution Jewish merchants, traders and scholars made to the economic and social upswing, above all in the cities. Later, the bishop Rudiger von Speyer, spiritual and secular lord of the city, paid them the same respect once again when he admitted that it was only the settlement of Jews that enabled a city to arise out of the “villa,” the village Speyer.

The Jewish settlements and communities in the area comprising today’s Germany came to be known collectively under the Biblical name of Ashkenaz. Ashkenaz was a descendent of the progenitor Noah, whose name was equated with the region “Germania.” Its inhabitants, the Ashkenazim, differed from the Sephardim, who settled primarily in Spain in the trail of Islam, which had been pushing westwards from the 7th century on. Sepharad is the Biblical name for the Iberian peninsula where, for a long time, a second center of Jewish cultural life came into being and flourished until Jews were expelled from Spain at the end of the 15th century in the wake of the Christian reconquering and the Inquisition and were scattered in all directions once again-to Morocco, northern Italy, the Ottoman Empire and, from 1600 on, to the Netherlands, among other places.

Stories of an Exhibition- Two Millennia of German Jewish History. The Jewish Museum Berlin. pp. 36-37.