The Isaiah Texts, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia 1994.

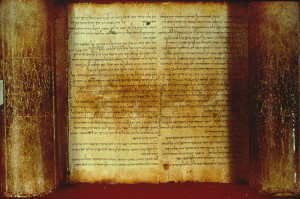

Looking at the two texts, we immediately recognize the coexistence of differing versions. Isaiah B represents a proto-Masoretic text, with only minor variation from the traditional Hebrew text as we now know it. On the other hand, Isaiah A represents the sectarian type, for it uses Qumran linguistic forms and, therefore, was most probably copied by members of the group.

In addition to these unique forms, this text also has many linguistic “modernizations”—forms and words common when it was copied (rather than when it was composed)—as well as simplifications. Some scholars have concluded, therefore, that the Isaiah A Scroll was intended for study and not for worship and that it represents a sort of common text, often termed “vulgar.” The Book of Isaiah was so popular that eighteen fragmentary manuscripts of this book have been identified in the collection from cave 4.

Although there are many minor textual variations in the Isaiah texts from Qumran, each of which would be instructive for our discussion, one particular example will be cited here, because it provides hints that some variants may tell us something about the literary history of the Bible.

In the Hebrew Bible that has come down to us, II Kings 20 and Isaiah 38 contain parallel accounts of Isaiah’s healing of King Hezekiah. Verse 7 in the chapter in Kings appears out of sequence because it assumes that the king has been healed, whereas in verse 8, he is still hoping to be cured. The problematic verse 7 does not appear in the parallel account in Isaiah 38-1–8 but instead is postponed until the end of the chapter as verses 21–22.

In the Isaiah A Scroll, the problematical text of verse 7, initially omitted by the scribe, was later added at the end of the line (after verse 6), continuing into the margin. For the scribe, then, there must have been some question about the proper placement of this verse. The scribe must have been aware of an alternative placement designed to solve the problems this text raises. What we will never know is whether the original scribe had a text of Isaiah without this problematical passage or whether the scribe simply made an error, which was then corrected by another scribe. To say the least, because of examples like this, study of the Book of Isaiah will never be the same after the finding of the Qumran scrolls.

Pages 173-174

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website