Study of the Bible

The importance of the Talmud to medieval Jewish life should not obscure the centrality of the Hebrew Bible on the medieval Jewish scene. The Bible, in different ways, formed the second pillar of Jewish life in medieval western Christendom. It was firmly planted at the heart of Jewish liturgy, bringing every Jew into constant contact with it; it was the grounding for the sermons that served as the central form of life-long Jewish education; it supplied the major symbols that oriented Jewish living in normal times and during periods of persecution and stress; it absorbed the creative energies of leading figures in the Jewish communities of both south and north; it served as the foundation upon which innovative thinkers in the realms of Jewish mysticism and philosophy built their systems; it was the major bone of contention in the ongoing Christian-Jewish debate.

Study of the Bible was part and parcel of the school curriculum, especially in its earliest phases. In a sense, Bible study continued all through a Jew’s life, via engagement with Jewish liturgy in both the synagogue the home. The daily and holiday liturgy was (and is) replete with numerous biblical passages and images, and the major Jewish festivals of the year were (and are) rich in recollection of biblical happenings and symbols. Thus, every Jew attending synagogue or celebrating a Passover seder at home was in fact fully engaged with the Bible at one or another level. This basic engagement was deepened by the sermons regularly delivered by the rabbis, which were based on biblical verses and incidents. Through these sermons, biblical perspectives, themes, and symbols were regularly reinforced.

Bible commentary absorbed the creative energies of many of the most important intellectual figures in the Jewish communities all across Europe. Once again, Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes in northern France emerged as a dominant figure, both in terms of his own writings and his stimulation of followers throughout northern Europe. In the south, the legacy of Jewish life under Islamic rule shaped somewhat different traditions of Bible commentary. Giant figures such as David Kimhi of southern France (Radak) and R. Moses ben Nahman (Ramban/Nahmanides) of Spain wrote important commentaries still widely read and pondered.

The centrality of the Bible, its stories, and its symbols meant that every spiritual movement developed by medieval Jews either began with reflection on biblical motifs or at least had to insure that its insights could be proven consistent with biblical thinking. Much of the Christian anti- Jewish polemical literature and the Jewish anti-Christian counter polemics revolved necessarily around disparate understandings of the biblical corpus and message.

Images

- Hebrew Bible, Fourteenth-Century Southern France or Northern Spain

- Hebrew Bible, Fifteenth Century Spain

- Hebrew Bible, Late-Fifteenth-Century Spain

- Illuminated Page from Thirteenth-Century German Manuscript of Rashi Commentary on Torah

- Illuminated Page from Thirteenth-Century German Manuscript of Rashi Commentary on Daniel

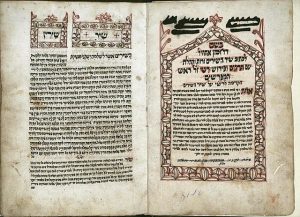

- Opening Page of Fifteenth-Century Italian Printing of Ramban’s Commentary on Torah

- Pages of Fifteenth-Century Italian Printing of Ralbag’s Commentary on Torah

Primary Texts

- Introduction of Abraham ibn Ezra to Commentary on the Torah

- Commentary of Abraham ibn Ezra to Gen. 22-1-2

- Commentary of R. David Kimhi to Gen. 22-1-2

- Commentary of R. Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi) to Gen. 22-1-2

- Introduction of R. Samuel ben Meir (Rashbam) to the Torah

- Commentary of Rashbam to Gen. 22-1-2

- Introduction of R. Moses ben Nahman (Nahmanides) to Commentary on the Torah

- Commentary of Nahmanides to Gen. 22-1-2

Secondary Literature

- N. M. Sarna, “Hebrew and Bible Studies in Medieval Spain,” The Sephardi Heritage, ed. R. D. Barnett (New York- Ktav, 1971), 323-366 .

- A. Grossman, “Biblical Exegesis in Spain during the 13th-15 th Centuries,” in Moreshet Sepharad, ed. H. Beinart (Jerusalem- Magnes Press, 1992), 137-146.

- N. M. Sarna, “Abraham ibn Ezra as an Exegete,” Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra- Studies in the Writings of a Twelfth-Century Polymath (Cambridge MA- Harvard University Press, 1993), 1-27.

- F. Talmage, David Kimhi, the Man and the Commentaries (Cambridge MA- Harvard University Press, 1975).

- M. Banitt, Rashi- Interpreter of the Biblical Letter (Tel Aviv- Tel Aviv University, 1985).

- M. Lockshin, “Rashbam as a ‘Literary’ Exegete,” With Reverence for the Word- Medieval Scriptural Exegesis in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, ed. J. McAuliffe et al. (Oxford- Oxford University Press, 2003) 83-91.

- E. Kanarfogel, “On the Role of Bible Study in Medieval Ashkenaz,” The Frank Talmage Memorial Volume, ed. B. Walfish (2 vols.; Haifa- Haifa University Press, 1992-3) 1-151-166.

Videos

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website